The 86-year-old Man Ray

had outlived most of his closest contemporaries when he died in Paris in 1976.

Tristan Tzara, the impresario of Dada, conked off on Christmas Day 1963. André

Breton, the petty tyrant of surrealism, succumbed to a heart attack in 1966.

Marcel Duchamp, Ray’s confidant and sometime collaborator, died in 1968,

followed by Picasso in 1973. Salvador Dalí was still alive but had already

ripened into florid mediocrity, capped by a pharmaceutical twilight in Spain.

As one of the last threads connecting the twentieth century’s major art movements,

Ray was owed a dutiful eulogy. But an obituary in The New York Times

struck an ambivalent tone. It described him more than once as an “impish” man

with a paunch, who had earned a “certain admiration” for his talents. “While

paying tribute to his versatility and inventiveness, [critics] felt that he was

fundamentally indebted to such other painters as Marcel Duchamp, Franz Marc,

Giorgio de Chirico, Braque, Leger and Picasso,” the obituary read.

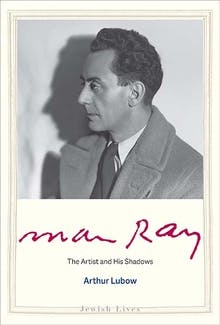

In his brisk new biography, Man Ray: The Artist and His Shadows, part of the Jewish Lives series from Yale University Press, Arthur Lubow writes that Ray’s “signature was an avoidance of a signature style.” Instead, Ray had technical epiphanies, sometimes stumbled upon by accident, that he exploited with increasing restlessness and often recycled throughout his career. He considered himself a painter above all, but the paintings were footnotes to the airbrush works (aerographs), rayographs, photographs, and sculptural objects that made his reputation. Much of his work shares an absurdist wit. Export Commodity (1920), an olive jar full of steel ball bearings, or the iconic Cadeau (1921), a flatiron on which Ray affixed a row of nails, have a mischievous incongruity. “I was called a humorist, but it was far from my intention to be funny,” Ray once said.

It also wasn’t his intention to play sidekick to other luminaries, but in Lubow’s biography, which takes an ensemble approach, Ray is regularly upstaged by a vivid coterie, including, most exuberantly, Alice Prin, the combustible muse better known as Kiki de Montparnasse. In this company, Ray often comes off as dull and bourgeois—a man who, Lubow notes, wore custom-tailored suits, flicked a Dunhill lighter, and drove a luxury car. By the epilogue, when Lubow cites Ray’s ballooning auction prices as evidence of the artist’s importance, you begin to apprehend the pinched radius of Ray’s genius. To quote Hilton Kramer of the Times, Ray was “a minor figure” in thrall to the heavyweights of cubism, Dada, and surrealism. His achievement is almost entirely bookended by the interwar years in Paris, after which he endured a long fade into self-repetition and triteness.

Lubow’s biography furthers the case that Ray’s gifts were primarily photographic. His portraits of Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, Jean Cocteau, Peggy Guggenheim, James Joyce, Luisa Casati, Virginia Woolf, Ella Raines, and many others defined the mood and texture of the cultural vanguard, while his rayographs were salvos from the future. The irony is that Ray, one of modernism’s exemplary image makers, measured himself against a tradition of continental European painting that was increasingly outmoded. He was usually ahead of the aesthetic curve during the first arc of his career. Today he occupies a confounding middle zone, his influence subliminal, vicarious, vaporous.

The book’s inclusion in the Jewish Lives series is curious given that Ray downplayed and sometimes disavowed his own Jewishness. He was born Emmanuel Radnitsky, in Philadelphia, in 1890. (The family Americanized their names to better assimilate; Ray’s younger sister Devorah clinched the most charming moniker: Do Ray.) His father was a tailor from Kiev, his mother a seamstress from near Minsk. Ray’s geometric compositions—and some of the imagery from his rayographs, such as scissors—may owe something to his parents’ professions. Ray was artistic from an early age. A perforated brass lampshade he constructed as a child delighted his family and was an object of fascination that he later resurrected. He won a scholarship to New York University’s architecture school but declined, much to his parents’ dismay. He saw himself as a serious painter.

At that time, the hub of American avant-garde art was the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, founded in New York City in 1905 by photographers Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen. More commonly known as 291 because of its first address on Broadway, the gallery showcased cutting-edge art, including the first U.S. exhibition of Matisse and the first exhibitions anywhere of Picasso, Brancusi, and Henri Rousseau. Stieglitz and Steichen were also passionate evangelists of photography, a medium that many critics still treated derisively. Whatever the rolling creative boil around 291, Ray was unprepared for the shock waves of the Armory Show in 1913, in which Picasso, Picabia, Duchamp, and other provocateurs imploded representational art and ushered in a radical modernity. “I did nothing for six months. It took me that time to digest what I had seen,” Ray later told a journalist.

In the meantime, Ray’s love life kindled. One undercurrent of the biography is an oblique fetishism that wafted into Ray’s romantic relationships and work. The impulse began early. He once asked his teenage sister to drop her dressing gown so he could sketch her breasts; she demurred. (Ray remained a lifelong boob man; a later photograph features disembodied breasts lacy with shadows, evoking the sudden skewed strangeness of a readymade. As late as 1971, he was still drawing breasts with a connoisseur’s relish.) Lubow diagnoses the young Ray’s virginity as “oppressive.” The artist found relief with Adon Lacroix, a poet whom he married in 1914. The marriage curdled under the sexual psychodrama of Lacroix’s infidelities and Ray’s jealousy. One morning he lashed her with a belt; on another he forced himself upon her “brutally.”

Such incidents recall something a patron once quipped about Ray’s art: “A sadistic streak runs through many of Man Ray’s objects.” Consider, for instance, Venus Restored (1936), in which the headless white bust of classical antiquity is bound in ropes. Or the Mr. and Mrs. Woodman photographs, in which wooden mannequins are posed in sexual tableaux, sometimes splayed against blank walls or ensnared in a cryptic metal contraption that suggests a medieval torture device. There’s also Ray’s friendship with the writer William Seabrook and his wife, Marjorie Muir Worthington, a couple who stoked Ray’s sadomasochistic urges. One evening at a banquet, Seabrook invited Ray to his hotel room, where a nude woman was chained to the bed and eating from a dog dish. Ray photographed Marjorie tweaking a woman’s nipples with pliers; in another photo, Marjorie sports an ornamental collar that immobilized her neck. In 1938 Ray painted the Marquis de Sade, a familiar touchstone for surrealists but, per Lubow, a personal “hero” for Ray. “I had whipped women a couple of times, but not from any perverse motives,” Ray wrote in his 1963 memoir, a sentence that encapsulates the milquetoast kinkiness that flickers through his art.

Another, more explicit current in Lubow’s biography is U.S. modernism versus European modernism. Ray moved to Paris in 1921, believing the city to be more zeitgeisty than New York. In a letter to a collector, he described New York as “sweet but cold,” while Paris was “bitter, but warm,” with “real life … real feeling.” Surely some of his resentment stemmed from his lack of success in New York; he had three solo exhibitions there but sold nothing. The city was brainwashed by money. It’s hard to dispute Ray’s assessment that Europe was still the frontier. By the 1920s, Dada was firmly entrenched there, and an expatriate community flourished on the Left Bank. Gertrude Stein played oracle and den mother to a burgeoning generation of writers and artists. Ray was just another American with an easel looking for his big break.

It came with his rayographs, cameraless images made by placing objects on photosensitive paper and exposing them to light. Ray didn’t discover this process, which dates back to the early days of photography, but he was the artist who pursued it most prolifically and imaginatively. “More than any other body of his work, the hundreds of rayographs reveal how Man Ray’s sensibility combined a visionary’s flights of inspiration with an engineer’s ingenious and methodical explorations of a problem,” Lubow writes. Even now the rayographs radiate a graphic showmanship that is minimalist and spectral; the miscellaneous objects—thumbtacks, coils of wire, scissors, combs, straight razors—are arranged with unfussy exactitude. The inverted colors and spatial interplay merge specificity and abstraction into still lifes that also look like X-rays of the industrialized psyche. Ray’s gift was to imbue images that might otherwise seem gimmicky with a kind of jumpy gracefulness; you almost expect the rayographs to burst into animated clatter.

Paris was also home to Kiki de Montparnasse. An artist model and self-made muse from the provinces, Kiki styled herself as an enfant terrible in the capital. “She certainly dominated that era of Montparnasse more than Queen Victoria ever dominated the Victorian era,” Hemingway wrote. Kiki reportedly didn’t wear panties; she sang bawdy ditties in public; she scandalized café owners by strolling in without a hat. She seemed to epitomize both the liberated flapper era and the demimonde in which women like her usually met tragic fates. (Kiki, addicted to alcohol and cocaine, died in 1953 at age 51.) Ray and Kiki dated for eight years—a seesaw relationship that the artist memorialized in photographs, including a few pornographic self-portraits. Artsier fare included Le Violon d’Ingres (1924), which Lubow calls Ray’s “most renowned photograph,” in which Kiki, nude except for a turban, faces away from the camera, two f-holes from a violin stenciled onto her back via darkroom chicanery. The image is a visual pun, with Kiki’s voluptuous body likened to a musical instrument and the conceptual overlay of “violon d’Ingres” (a phrase understood to mean “hobby”) alluding to the fact that the nineteenth-century painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was an amateur violinist. For those in the know, Ray seemed to imply that photography was his hobby, although by that point it was also his livelihood.

Ray’s other Paris conquest was Lee Miller. They met when the artist was almost 39 and Miller a blonde 22. She was an American model with a believe-it-or-not origin story: She was crossing a street in Manhattan one day when a stranger pulled her to safety from an oncoming car; the stranger was Condé Nast, who offered her a job in fashion. Like Kiki, Miller became Ray’s model, muse, and collaborator. She was a photographer herself who later became a war correspondent for Vogue; she documented the London Blitz and Nazi concentration camps. Together, she and Ray experimented with solarization photography, which results from overexposing film during development. These images almost resemble graphite renderings, but their intrigue dissipates quickly. Much the same can be said of the couple’s relationship, which soured after two years, scuttled by Ray’s jealousies. “Man Ray couldn’t accept Miller’s social and sexual independence,” Lubow writes. It was a pattern that persisted throughout the artist’s life. Even by the 1970s, when he was married to the dancer Juliet Browner, he liked to have his wife sit quietly in the studio while he painted. “We didn’t talk. He just wanted to feel my presence,” Browner wrote. Ray seemed unable or unwilling to grant the women in his life full autonomy, a blind spot reflected repeatedly in his art, where women are objectified, or piecemealed into sexual ballast.

The advent of World War II drove Ray back to the U.S. He settled in Los Angeles, an unlikely harbor for an artist so associated with the chic avant-garde. He intended his exile to be temporary, but he stayed for more than a decade. He dubbed California a “beautiful prison,” and his West Coast years were accordingly ones of repetition and inertia. Although he continued to produce work and mount ignored exhibitions (one show was called “To Be Continued Unnoticed”), Ray was rudderless. He returned to Paris, where, in 1963, he signed a contract to fabricate editioned replicas of his past artworks. While this sideline made money, Lubow argues that it turned Ray’s “mysterious objects into souvenir trinkets.” For his part, Ray puffed up this commercial enterprise. “It is permitted to repeat oneself as much as possible,” he wrote. “Nothing is more legitimate and more satisfying.” Whether or not he meant that, the money rolled in. He died, rich, in Juliet’s arms.

If the mark of a good biography is that it reveals something unexpected about its subject, or sheds new light on the subject’s work, then Lubow’s brief volume only partially succeeds. While it crisply synthesizes the existing commentary on Ray, the artist remains elusive. This was by design. “I am an enigma,” Ray once told his niece. To researchers, he was even more pointed: “I abhor all biographical facts, consider them useless and distracting from one’s accomplishments.” He gave differing accounts of his family and influences, an inscrutability that was inherent to the surrealist and Dada projects but that in Ray also thickens the smog around his work. Unlike Duchamp, Picasso, Pollock, Warhol, Bacon, Rothko, and other twentieth-century grandees, Ray isn’t a brand. His style is varied and amorphous, so that even art buffs sometimes have trouble conjuring a particular Ray image. His work, like his life, can feel haphazard and trackless.

On the matter of Ray’s influence, Lubow also basically shrugs. He name-checks Jeff Koons as a contemporary analogue to Ray’s pornographic husband-and-wife photos, but the comparison is superficial. He also quotes Robert Mapplethorpe, a Ray aficionado who believed the artist was the most important photographer of the twentieth century, without considering the affinities between the two men. More strangely still, Lubow doesn’t delve into Ray’s obvious sway over fashion photography. Guy Bourdin, Paolo Roversi, Sarah Moon, Ellen von Unwerth, Mert and Marcus, Helmut Newton, and other photographers all bear traces of Ray’s dreamlike atmosphere. Lubow gawks instead at Ray’s auction prices.

These numbers are impressive, but dollars don’t illuminate Ray’s endurance in the culture. He’s there, though: diffuse, distilled, continuing—he would have hated this—unnoticed.