“Man,” observed the American anthropologist Marshall Sahlins in his pathbreaking 1985 work, Islands of History, “lives by a kind of periodic deicide.” The specific god-killing he had in mind was heart-stoppingly real. In January 1779, the British explorer James Cook arrived in the waters around the Hawaiian Islands. His timing was impeccable: He came ashore during an annual indigenous rite known as the Makahiki, when locals celebrated the future return (and rule) of the fertility god Lono. Cook’s visit was seen as fulfillment of the prophecy, and the islanders greeted him as a deity. But his celestial promotion did not end well. Lono was supposed to be invincible. Cook, who was ultimately killed on the beach, proved not to be.

Ours is a world grown unfamiliar with the notion that humans can literally become gods. Fates like Cook’s have become odd curiosities, thanks, in part, to what the poet Stephen Spender called the “spiritual astigmatism” of the modern age: the tendency of scientific rationality to illuminate certain phenomena while obscuring others. The tale of Captain Cook helps modern readers believe that they have triumphed over the irrational past, just as it once made the captains of European empire feel superior to the indigenous societies they sought to conquer and exploit.

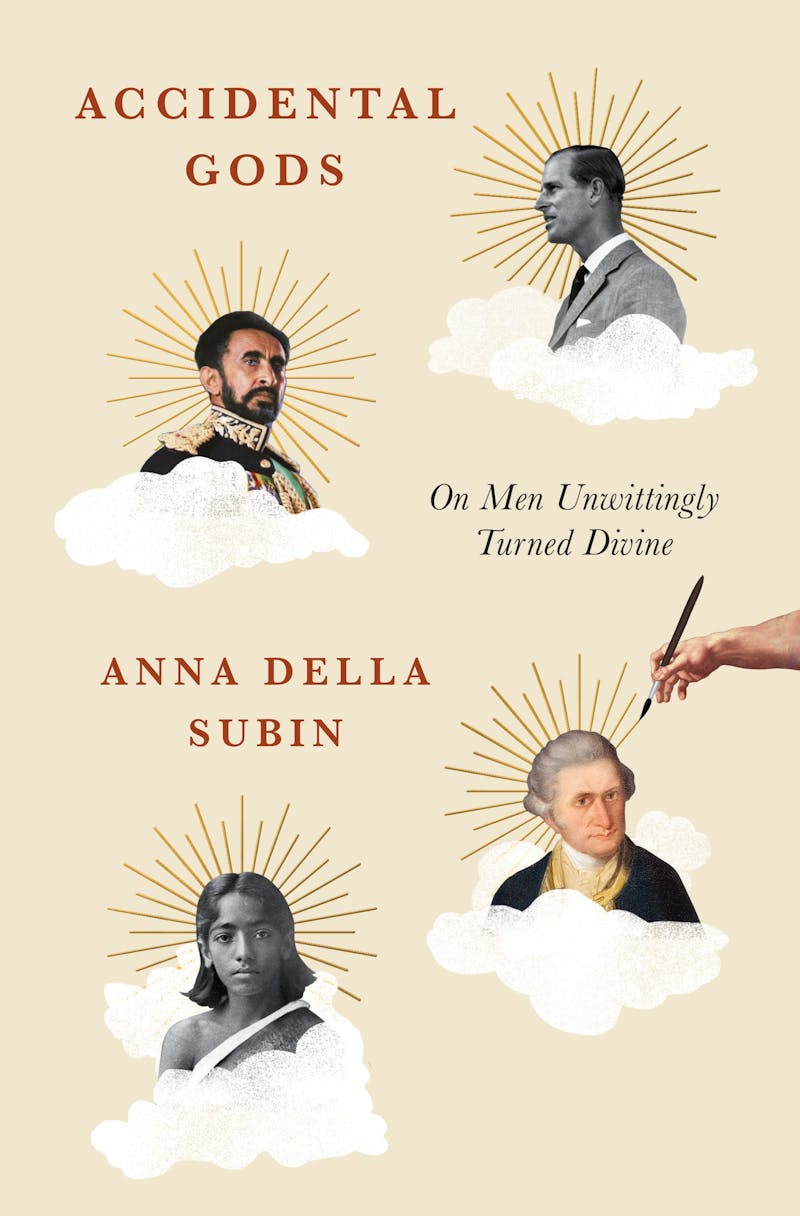

Yet as Anna Della Subin demonstrates in Accidental Gods: On Men Unwittingly Turned Divine, stories of deification tell us as much about how power is wielded on Earth as it is in heaven. Even today, the idea of inadvertent godhood is more alluring than we realize. With a stylish, playful, at times almost biblical authorial voice, as well as a keen eye for history’s most revealing paradoxes and charming cul-de-sacs, Subin restores to view the lost tales of modern men (and a few women) transformed into gods before our very eyes. Some of them, like the Spanish conquistadores, were elevated with their winking consent and in service of ulterior motives. Others were praised against their will and despite their protestations.

As Subin assembles this dazzling pantheon of inadvertent deities, from Mahatma Gandhi to the zombie spirit armies of French colonial Niger, she also returns them to their proper place at the heart of modern histories of race, imperialism, and anticolonial resistance. To exclude deification from our field of vision, to bracket off these accidental divinities from Real History as weird or nonsensical, is to misunderstand how white Europeans cemented their global power—as well as how colonized people profoundly challenged it.

In 1974, a man named Jack Naiva, the indigenous chief of a village called Yaohnanen in the South Pacific nation of Vanuatu, saw a living god. “I saw him standing on the deck in his white uniform,” he recalled. “I knew then that he was the true messiah.” The deity in question was the British monarch’s husband, Prince Philip, vacationing nearby aboard the royal yacht Britannia. Like Cook before him, he found himself fêted as a god on Earth.

After hearing about this elevation, Philip appears to have been rather delighted. In 1978, a delegation was sent to Yaohnanen to deliver a signed princely portrait. Philip’s island worshippers reciprocated by sending their god a traditional pig-killing stick. Then, astonishingly, Buckingham Palace staged a photo shoot: Philip stood outdoors, the weapon held firmly in his hand, a dark suit draped upon his athletic frame. The photo was received in Vanuatu as further proof of his godhood. As the islands neared independence in 1980, French officials accused the British of taking advantage of their prince’s divinity to preserve influence in the region. Not a preposterous claim.

One way to read Accidental Gods is as a sort of guidebook to the various types of modern divinities one might encounter in the wild. Philip is an excellent representative of the first and most familiar category: Europeans endowed with heavenly powers by the indigenous peoples they wished to rob or control or study or kill—who then seized upon their newly celestial status to reinforce the imperial project. It’s a long and disgraceful list.

It happened first to Christopher Columbus, we’re told, in 1492. Making landfall in the Caribbean, he was met by indigenous crowds who mistook his Spanish expedition for a celestial envoy. “They threw themselves into the sea swimming and came to us,” Columbus wrote in his diary. “We understood that they asked us if we had come from heaven.” The islanders made clear, he reported, that “if I wanted anything, the whole island was at my disposal.” He claimed their lands for Castile. No one could understand his proclamation.

Roughly the same thing happened to the Spanish explorer Hernán Cortés, who blazed his bloody trail through Aztec Mexico nearly three decades later. A European source reports that the Aztec emperor Moctezuma, believing Cortés to be an incarnation of the feathered serpent god Quetzalcoatl, handed over his possessions and territories to this newly arrived divine ruler. Tales like these became “foundational myths of the colonization of the Americas,” Subin writes, “a way to justify conquest and maintain European supremacy in the fragile settlements.” Fortuitously, it was all recorded for posterity by the new gods themselves.

Several centuries later, amid the bloody misadventures of high imperialism, the appeal of acquired divinity had not yet worn off. Queen Victoria experienced what Subin calls a “jungle apotheosis” when the residents of certain villages in India started to venerate her as a god, worshipping coins marked with her profile and praying to silver serving dishes that she had bestowed as gifts. British India blossomed with minor colonial gods, too. In 1846, a British minister named Thomas Ragland reported from the town of Illamulley that “the most dreaded deity of the place” was a figure named Pooley Sahib. “And whom do you imagine this mysterious personage to be?” he asked his correspondent. “You will be as much astonished as I was to learn that he is nothing more nor less than the spirit of an English officer, of the name of Pole, or Powell, or some other similar name.” The shrine dedicated to Pooley Sahib drew sacrifices of liquor and cigars, which villagers offered to ward off death and disease. Around the same time, a devout religious community of Sikh and Hindu worshippers began venerating a “raging god” known to many of them as Nikalsain, said to be a particularly vengeful and destructive deity. The spiritual germ in this instance was Major John Nicholson, an Irish Protestant soldier and official killed in the 1857 Indian Revolt.

Sensational stories like these traveled back to Britain, the breathless stuff of newspaper columns and parliamentary debate about the Empire. They also swirled into the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge, where they formed the basis of modern religious scholarship. Orientalists and philologists like Max Müller, who never traveled to India, used reports of deification in the colonies to construct powerful theories of world religion that placed European spirituality at the apex. The ability (and desire) to perceive the Infinite, Müller argued, was a universal human trait. Over time, evolved societies realized that the Infinite was none other than God: singular, invisible, and omnipotent. Müller thought that other forms of religion around the world were locked into earlier stages of spiritual evolution. Signs of backwardness included the tendency to worship objects, mythical creatures, or, he might have chortled, even other living human beings. How convenient!

Although colonial officials claimed to be appalled by all this god-making, they used it to justify their conquests. Europeans in the nineteenth century thought that mistaken deifications demonstrated the backward thinking and racial inferiority of their colonial subjects. This belief allowed them to argue that empire was benevolent as well as necessary. “Like an unwitting Atlas, holding the globe on his shoulders,” Subin writes, “the deified British officer propped up an empire.”

In 1882, the British poet, scholar, and colonial administrator Sir Alfred Lyall commented that there was much more to cases of Europeans being transformed into local deities than initially met the eye. Yes, he wrote, Indians were treating men like Nicholson as gods due to awesome wonder, a feeling brought about as they marveled at the trappings and power of British civilization. But Lyall also sensed a more subversive motive: pity for their own hapless colonizers, pointlessly and gruesomely killed far from home. On some level, they felt that the British were rather pathetic. Turning them into gods was a way of seizing the emotional upper hand while also controlling how the occupiers would be remembered.

Subin notes that the history of modern god-making can also be told as a tale of resistance. Elevating other human beings into living gods was a powerful way for colonized peoples to “imagine alternative political futures, wrest back sovereignty, and catch power.” In 1925, a quarter-century into the French occupation of the West African nation of Niger, imperial officials in the capital of Niamey began to hear unsettling reports about a “kind of crazy wind” that had been sweeping through the city. Women and men were tumbling into trances, possessed by the spirits of French administrators who had died on duty. The supernatural beings, known as Hauka (or “madness”), imitated their imperial oppressors by wearing pith helmets, drinking gin, and marching in mock military formation. As this army of colonial spirits grew, its haunted zombie-officers began renouncing French rule and planning for resistance. French officials worried that the Hauka represented “serious trouble” and called their own deified spirit-doubles a “sect that copies our administration and wants to supplant our authority.”

While the Hauka spirits were unnerving, however, they didn’t instantly end French rule. They occasionally refused to recognize the authority of certain officials. They reclaimed the bureaucratic language of colonialism for themselves, and their spirit-medium colonial look-alikes solved local problems. For decades, the Hauka lingered as a force in Nigerien society, a simmering cultural resistance to European rule that regularly spooked imperial officials. The other shoe finally dropped in 1974, when a collection of Hauka-possessed Nigeriens deposed the nation’s first postindependence ruler, formed a spirit-led regime, and expelled remaining French soldiers from the territory. Possession by dead Europeans, one Hauka official told an anthropologist, “is in our blood. All of us are touched by it in one way or another.”

The blundering apotheoses of explorers like Columbus and Cortés, then, are just one side of the story. In reality, colonized societies divinized human beings not just to accidentally give up power, but as a way of getting it back. Perhaps more frequently than Subin would care to admit, the resistance made possible by godhood was more symbolic than physical. Yet while deification may not by itself have toppled empires, it did help fuel anti-colonial forces by offering new ways of thinking about authority—on heaven as well as on Earth.

The long and tumultuous campaign for Indian independence, perhaps the most dramatic success of the anti-colonial movement, was itself turbocharged by apotheosis—unwanted, in this case, but not, in the final accounting, unhelpful. Mohandas Gandhi became known as “Mahatma” (or “great soul”) when the title was bestowed on him by Annie Besant, an unconventional British activist who determined him to be a quasi-god within Theosophy, the spiritual movement she chaired. Gandhi was suspicious and explained, “the word ‘Mahatma’ stinks in my nostrils.’” As he insisted in 1922, “I lay no claim to superhuman powers. I want none.”

But the rumors of Gandhi’s celestial status only grew louder. As he traveled India in the 1920s, building support for independence through nonviolence, he was met by passionate and ecstatic followers who believed him to be the latest incarnation of Vishnu. It was said that prayers to Gandhi could make you rich, return items that you had lost, or inflict pain on your enemies. One newspaper reported that a little girl had magically turned one grain of maize into four by invoking Gandhi’s name. Although he regularly renounced his own godhood, it’s not hard to see how divinity served Gandhi’s purposes—and those of Indian anti-colonial nationalism. Whether deities or not, charismatic leaders always benefit from the perception that they possess special qualities or unusual powers. It makes them worth following and suggests that the unachievable might finally be within a people’s grasp.

Yet the shift from authoritarian or imperial rule to democracy also depends upon a leap of conceptual faith. For the people to rule, they have to be able to imagine sources of earthly political authority that lie beyond tradition or paternalism or race or the terror imposed by soldiers’ boots. Paradoxically, Gandhi’s celestial status provided Indians with an alternate source of earthly power and legitimacy. It may not have been as egalitarian as he wished, but it may have ultimately made democracy and independence more thinkable.

As well as deifying Europeans for their own purposes, in other words, colonized societies started to worship something even more transgressive and powerful: themselves. “Let all other vain Gods disappear from our minds,” argued the charismatic Bengali Hindu monk Vivekananda in 1897, speaking in Madras about India’s future. “This is the only God that is awake: our own race … The first Gods we have to worship are our own countrymen.”

Europeans had already and always been worshipping themselves. Chroniclers assumed, for instance, that there was a good reason why explorers like Cortés or Columbus were mistakenly celebrated as gods. It was their whiteness as much as their technical prowess, many believed at the time, that had prompted indigenous peoples to mistakenly see them as divine. It’s these beliefs that make Subin’s history of accidental god-making also, and inextricably, a story about race. As racial theories calcified in the nineteenth century, the divinity of whiteness became a critical part of the stories Europeans told about their past, present, and future.

Many of these tales, Subin reveals, rested on calamitous mistranslations. Explorers heard what they wanted to hear, often converting complex indigenous concepts (like the Aztec term teotl, used to signify many different forms of divinity and authority) into the narrow parameters of monotheism. They did the same with race. When Henry Hudson arrived in North America in 1609, for instance, the Lenape people greeted him and his comrades as Shuwanakuw. The Europeans thought this was a statement about their “white skin,” but it was actually a comment on their beards. The Lenape were only comparing them to otters (hairy creatures emerging from the ocean), not welcoming them as white gods-on-Earth. This was handily lost in translation.

Subin observes that notions of whiteness and divinity remain closely intertwined. During the civil rights era, she writes, Ku Klux Klan leader Wesley Swift argued from the pulpit that white people were uniquely blessed with “celestial life,” making racial divinity “the core curriculum of white supremacist theology.” Similar notions froth and foam today on Stormfront, the radical-right online forum where users treat Hitler as holy and murmur to one another that “God is in our aryan DNA…we must do everything to be eternal.” It’s also common for white supremacists to borrow stories or symbols from Norse mythology in a bid to confirm their superhuman purity. (Look no further, alas, than the furry Viking hat and runic tattoos of the “QAnon Shaman,” arrested for his role in the January 6 siege of the U.S. Capitol.) For his part, President Donald Trump enjoyed being seen as a divine instrument. In online memes and overwrought paintings, he is sometimes depicted in the company of Jesus Christ: two heavenly white saviors.

Trump was thrilled to receive the fervent devotion of his Christian and white nationalist supporters, using his quasi-divinity to advance his own selfish interests. But his celestial promotion makes more sense, after reading Subin’s book, as a kind of resistance. What Trump’s supporters are challenging is not empire but rather the liberal, pluralistic, and multiracial global order that succeeded it. By this light, the president’s deification is not the strange mania of easy marks, keen to be hoodwinked by a trashy gratifying huckster. It is a meaningful, deliberate, and destabilizing challenge to democracy.

Perhaps it isn’t all that surprising. For if one marker of our modern democratic crisis is that “the people” no longer feel so exalted or sovereign, their world-making powers diminished and faith in their own self-made authority waning, it may only be a matter of time before someone or something else begins to seem worthier of collective worship.