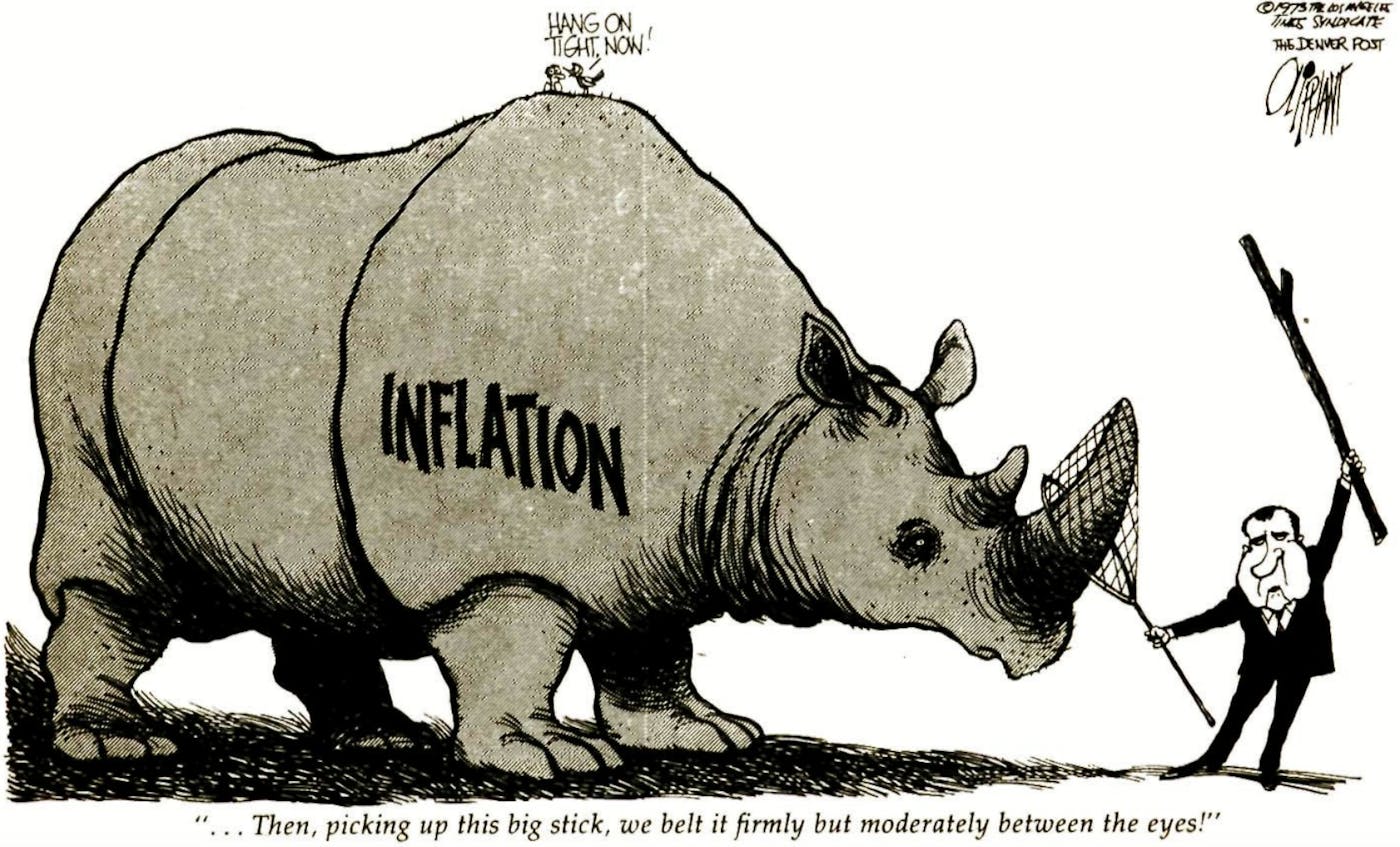

This is a hell of a time, I know, to seek attention for a fresh approach to the problem of inflation. Who is interested? After five years of an administration that made curbing inflation its number one domestic priority and a surfeit of Nixon’s, Shultz’s and Stein’s confident promises, glib forecasts and disastrous outcomes, after enduring the “classic cure” of a recession intentionally induced by tight fiscal and monetary policies, and after waiting out a long period of phased direct wage and price controls, only to see prices explode in 1973 to a degree unmatched since immediately following World War II, the American people numbly realize they are in for it, and that even higher price increases must be expected into the indefinite future. Frustrated and angered, the question people ask themselves has got to shift from “What can the government do about inflation?” to “If more inflation is inevitable, how can I protect myself, and the devil take the hindmost?” This is one reason why we stand poised today on the verge of an inflation far worse than any in current history. I intend to examine why this is so and to explore the choices we have for dealing with it.

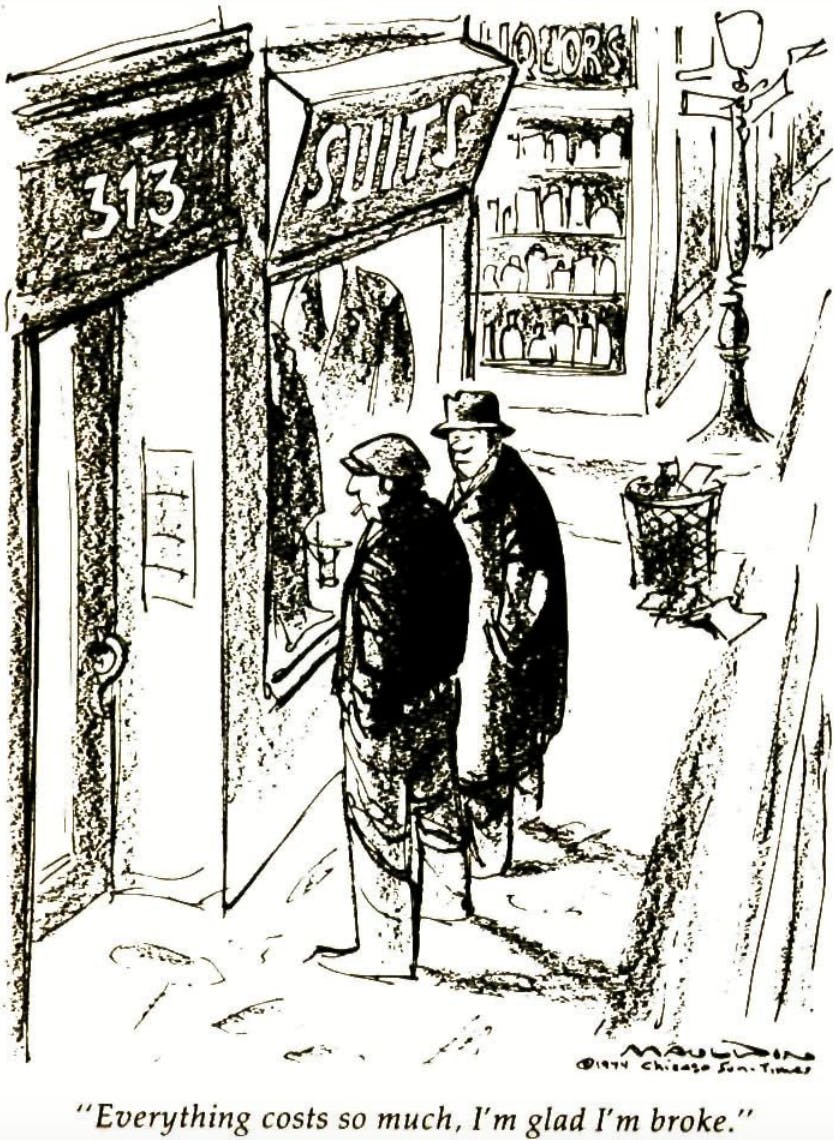

While the consumer price index rose by some nine percent in 1973, wholesale prices climbed on average at twice that rate. Since these must be reflected in consumer prices, this is a clear indication that substantially higher consumer prices are on the way. The skyrocketing prices of basic commodities in spot and future markets are even more dramatic signals. Wheat and soybeans at over six dollars per bushel, beef on the hoof at 49 cents the pound, potatoes over 12 cents, sugar over 18 cents, cotton about 70 cents, cocoa at 65 cents–such producer prices range from two to several times their levels of a year or two ago, and the end is not in sight. Silver commands nearly six dollars per ounce, gold $150. Land values, and those of “name” paintings, jewelry and precious stones have risen to incredible levels. They all play an important role in the psychology of expectations and contribute to the feeling expressed by a man I know: “Money is going out of style.”

The influence of continued oil and energy shortages will of course be with us for years to come. The prospect of huge budget deficits fired during the late 1960s by the Vietnam war stretches out into the indefinite future, not least because we have learned to fear economic stagnation even more than we fear inflation, hence “stagflation.” The extremely high interest rates we fostered “to fight inflation” themselves contribute importantly to higher costs and prices, and long-term rates especially show little prospects of declining. Environmental concerns occasion us to curtail the use of high-sulphur fuels, and of offshore drilling and pipeline construction, which increase the cost of purer fuels, and limit overall output. At the same time the massive investments required to reduce pollutants will not result in additional output and will thus contribute to higher costs and prices (at the same time they improve the quality of life). The giant Russian wheat purchase, which contributed so much to soaring grain prices, was to be sure a one-shot affair. But it coincided with the virtual exhaustion of our surplus food reserves, which for a long time operated to moderate price increases. Further it now appears that the disastrous droughts and crop failures that have beset Asia and Africa in recent years may recur more frequently than in the past due to an observed southward shift in the monsoon on which their agricultures depend. The devaluations of the dollar have increased import prices and costs in the domestic economy. At the same time, by making exports cheaper and achieving a favorable balance of trade, they reduce the quantities of goods otherwise available on the home market, thus contributing again to higher prices. As everyone knows the concentration of ownership and production in most of American industry supports an administered price structure more likely to rise than it is to fall when production declines. Underlying all these influences is the population explosion that is currently adding some 90 to 100 million lives year by year to the world’s population, all of whom need food, clothing and shelter, and adding to the vastly greater quantities of all goods and services needed to improve the intolerable living conditions of some one billion of the Earth’s present population.

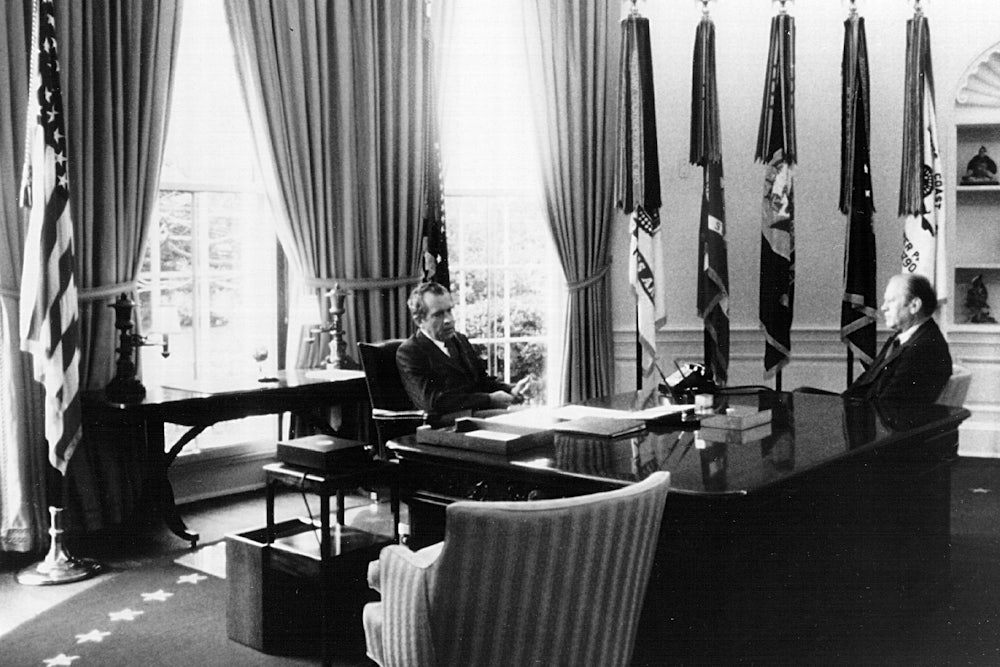

These are objective economic facts. When I turn to important subjective factors in the outlook for future prices, I must for considerations of space ask the reader to use his imagination when I suggest that demoralization—of workers, of consumers, of sellers, of government itself—will from here on out play an even greater role. This demoralization has to do with much more than just the course of prices. It reflects Watergate, pollution, runaway technology. It reflects the excesses and uglinesses of urbanization and slums and crime and noise and filth and drugs and corruption—the whole bit. One might say it reflects, for the first time in our national history, the loss of confidence that the future will be better for all of us. There is a growing sense that we have lost control, that things are going from bad to worse. All this conditions behavior. Workers care less and less about their jobs and job performance; some express their resentment in subtle sabotage. Productivity and quality decline. Consumers lose whatever sense of outrage they might once have had when faced with outrageous prices for goods and services. They begin to view them as ludicrous, respond with insecure laughs and shrugs. Since prices will obviously be higher next week or next month, why resist buying today? Sellers are subject to their own form of demoralization, as former limits on what the market will bear rapidly dissipate. And if today’s inventories will in all likelihood be replaceable only at higher cost levels tomorrow, why not protect tomorrow’s profit margins today? So far as government goes the Nixon administration stands in as great disarray on the price front as it does with respect to Watergate. It can scarcely wait to withdraw (as in Vietnam, “with honor”?) from the battle.

Prices reflect the economic relations within the society. If these relations—between workers and employers, among worker and employer groups, between creditors and debtors, workers and farmers, the working population and the retired, and so on—if these remained undisturbed by price changes, whether up or down, inflation (or deflation) would bother no one. Small changes, slow changes, are relatively easy to accommodate. But changes of some magnitude, which are concentrated within relatively short periods of time, disturb previously existing economic relations profoundly. They favor the interests of some groups in important degree; at the same time they injure the established interests of other groups already hard-pressed. At some point in the inflationary process, economic groups become variously aroused, protective, combative, aggressive. They gird themselves for political and economic battle to protect what they regard as rightfully theirs, or to enlarge what they consider their inadequate share. All prices are involved—the price of work (wages), the price of money (interest), the price of land and housing (rents), the price of risk-taking and management (profits)—for each price is someone’s distributive share, someone else’s cost. When the major economic groups in the society are aroused to this kind of struggle, rapidly spiraling prices—a galloping inflation—must ensue.

One cannot predict at what precise point so sharp a conflict will erupt. To me the reading is quite clear. One has only to listen to housewives waiting in line at the supermarket checkout counter, read of angry independent gas station and trailer truck operators, and consider the grim forecasts of trade union leaders about the kind of wage demands to anticipate in 1974, to sense the gathering storm. In my judgment we are close to the point now, if indeed we have not already passed it. (In 1949 the general price index in Brazil rose by 7.1 percent. From that point it drove inexorably upward in large though irregular annual leaps until, in 1964, general prices averaged nearly 50 times as much as in 1949. The annual inflation rate for 1964 exceeded 90 percent!) I don’t mean to suggest that we shall necessarily repeat the experience of Brazil, or of other countries that have also undergone runaway inflations. I cite the Brazilian case to show what sort of experience, in the absence of intelligent countermeasures, is possible. If galloping inflation, then, is in near prospect, what sorts of choices do we have?

Another try at the “classic cure”—tight fiscal and tight monetary policy—is not one of them. These indirect controls work, to the limited extent they do, by hitting the weakest hardest. Housing construction, small businesses and state and municipal governments (and their services) are most adversely affected by scarce and high-cost money, while increased unemployment takes its most severe toll among the weakest sections of the working class—Blacks, youth and the unskilled. They cannot effectively curb spending by giant corporations that generate the cash they need by raising prices and profits and huge depreciation cash flows. In any case while such policies might (conceptually) be appropriate in the earlier stages of a boom period, when they might moderate the pace of price increases with fewer adverse effects, they would constitute a major social surgery at this stage of the game, as even the President recognized in his state of the union speech.

It is worth considering whether there are not a number of selective measures which might, in combination, contribute significantly toward a price slowdown. In the oil and energy fields we could use allocations and rationing to stretch limited supplies more equitably. We might also place oil production, refining and distribution under regulation as a public utility industry as is the case with electricity and gas, although not coal. At the least we could set up, as Sen. Adlai Stevenson recommends, an equivalent to the TVA in oil, to create an economic yardstick on private industry operations and prices. In the case of major export crops like wheat and soybeans, where abnormally high foreign demand has forced prices up to levels that afford huge windfall profits to producers, we should institute export taxes to recapture the windfall, and use the proceeds to subsidize their domestic prices. (All producers would thus receive a weighted average of the export and domestic prices.) We might also (this would require acting in concert with industrial oil importing nations) impose export taxes on goods sold to oil exporting nations, and use those proceeds to subsidize lower oil prices here. We could lower the discount rate selectively, and require banks to set aside adequate credits for lower-cost lending to priority purposes such as non-luxury residential construction. We could enact much tougher consumer protection measures (quality controls, advertising claims, etc.) and enforce antitrust laws more vigorously to ensure that consumers got better value for their money. We might introduce curbs on installment credit, to reduce consumer demand. We could eliminate tax credits now accorded to investment, except in cases where new investment was urgently needed. We could foster the rapid extension of profit-sharing in collective bargaining agreements to temper wage demands and to make possible larger returns to labor without increasing wage costs.

All these measures have attractive aspects, and there is a good case for most of them now. For others however—installment credit curbs, investment tax credits—the timing may not be right because of their employment effects. Neither is a “stagflation” year, with its declining profit margins, a very good time to try to sell organized labor the profit-sharing idea. The possibilities of selective measures are thus promising but limited—too limited, and too late, to be adequate in the present situation.

In the opinion of many President Nixon’s price control program failed because of the premature liquidation of the relatively tight Phase II wage and price controls, rather than because of a basic flaw in the controls idea. Would then a return to a Phase II equivalent work? One fatal infirmity in the Phase II controls was that farm prices were exempt. A second essential point is that if wage arid price controls are to be accepted over a long period of time, groups whose incomes are controlled must perceive that they are not sacrificing a great deal more than others. A control system must therefore a) affect all income receivers in roughly equal measure—meaning that it must apply to rents, interest, dividends, executive salaries and profits, as well as to wages and prices, and b) it must be flexible enough to permit the timely and adequate adjustment of the inequities that were frozen into the structure when the controls were imposed. Freezing incomes is easy; it requires only fiat. But living with the income relations that exist at any time is more than difficult—it is impossible. The controls required by a comprehensive incomes control system (for that is what it comes to) must inevitably go far beyond it (except in the case of a major war, when such controls are accepted for the duration of the emergency only). Such a system must inevitably extend through allocation, rationing and production and use controls to a fully planned national economy. This may well be the way the country (and the world) will inevitably go; it may also be the most desirable way to go. But are we ready for it? Bearing in mind that national planning always raises the questions who plans what, for whose benefit, are we ready to risk how these questions would be answered? I admit to great trepidation on this score, as well as on the simpler question of whether we are smart enough, and the more subtle question of whether we know what moral and social values we would want to build into a comprehensive planning system.

Inspired by the moderate success of housewife resistance to high beef prices in 1973, housewives in the Boston area alarmed by threats of one dollar per loaf of bread this year are organizing to strike again. We shall no doubt see many similar actions across the country as food prices continue to rise in the months ahead. It is tempting to speculate on how effective a truly well organized buying strike or slowdown could be, if most housewives participated and if their action were extended across the board to the entire range of consumer goods. Suppose for example that every housewife determined that for one full month she would buy only the cheapest foods in the minimal amounts necessary to get by, and deferred all postponable purchases, buying only those things absolutely essential for strictly current needs (baking, patching, repairing, sewing, etc. wherever possible). In this scenario stocks would swiftly pile up on retailers’ shelves, retailers would cease to reorder, and the jam would soon backtrack to wholesalers, jobbers and manufacturers. Within a matter of weeks, pressures would build up enormously. Production lines would slow down and cease operations, workers would be laid off, and businesses all along the line would begin to experience unsustainable losses. Would not prices be forced down?

Indeed they would if one can accept the reality of the scenario. But if one can, how does one then envisage the companion scenario—that describing the effect of such a buying slowdown on the husbands and providers of all these households? Do they say, “Great work! Keep it up.”? Or do they come home and say, “Look what you stupid women have done. You’ve cost me my job.” In pitting against one another the disparate interests of the family in earning a living, and buying it, a major buyers’ slowdown invokes a dangerously unpredictable outcome. One can of course think of what might be a more practicable alternative—namely a rolling buyers’ boycott that would be selectively applied to only one commodity at a time. Thus housewives might strike first against beef, then poultry, then cereals, then fish, then clothing, then ... . The danger of work layoffs would in that case be similarly selective and limited, temporarily severe for those affected, but not calamitous for the nation, and permitting those working to help out those temporarily unemployed. But if mobilizing a general buying slowdown is difficult, how do you organize people across the country to initiate and carry through so disciplined a maneuver as a rolling, selective series of boycotts?

Professor Milton Friedman has recently advised that we emulate the policy adopted by Brazil in 1967 of incorporating purchasing-power escalator clauses into all important monetary contracts, to correct or compensate them for price changes. Thus in addition to the well-known cost of living clause in wage contracts, similar adjustments would be made in the interest paid on bank deposits, on government and business loans and so on. Personal exemptions under the income tax, and tax brackets, are similarly “corrected.” So also is the book value of business plant and equipment, thereby permitting larger allowances for depreciation and reducing the amount of profits on which taxes would be paid. “A world of zero inflation,” says Friedman, “would obviously be better. Yet . . . with it [the monetary correction] they [Brazil] currently experience less economic distortion from a 15 percent inflation than the US, without it, experiences from a 9 percent inflation.” Consequently “it is past time that the US applied the lesson.”

It is true that monetary corrections, applied across the board to all monetary contracts and price relations, would greatly reduce, if not eliminate, the changes in economic relations which, as I pointed out earlier, create such havoc and generate such group conflict, when prices change abruptly. And if only those relations were reasonably equitable to begin with, a comprehensive system of monetary correction could undoubtedly make even a high rate of inflation tolerable, and by that token minimize the group price-income conflicts that constitute the inflationary spiral. However what the good professor did not mention in reporting on the Brazilian “miracle,” were two facts of more than negligible importance. First that the economic relations prevailing in Brazil are such as to keep the majority poor in a state of bondage (studies of income distribution there suggest that the poor are even worse off now, after years of spectacular economic growth “successes,” than they were before); and second, that to enforce continuation of this “miracle” and prevent recurrences of the violent class economic conflicts that sparked galloping inflation in the early 1960s, the military government must continue to exercise its savagely repressive dictatorship.

This brings us to our next alternative and in my judgment the only real solution —social justice. We need, first, to provide liberal income supplements to the working poor, to provide more generous assistance to the aged, to fatherless families, to the disabled and helpless, and to guarantee public employment to those who are unable to find jobs in the private economy. We need to provide a national health service, an abundance of decent low-cost housing and adequate urban and intercity public transportation at moderate cost. We need to provide generous scholarship assistance for the children of all but the well-to-do to enable them to pursue their higher vocational, technical or academic interests beyond the high school level, and supplement this with tax relief assistance to their parents for the costs they bear. Workers stuck in dead end jobs should also be enabled to take training courses that would enlarge their opportunities. Major new public recreational and cultural facilities and services should be created. Revenue sharing with state and local governments should be adequate to help them in significant degree to supply essential services and ease the burden of crushing sales and property taxes. This will do for a start.

How do we pay for all this? The key strategic requirement here must be that the methods used again contribute to social justice by eliminating inequities and moderating disproportionate burdens in the tax structure. The fiscal dividend resulting from the full use of more productive resources, the elimination of the notorious loopholes in the existing tax structure, and the elimination of waste in the defense budget are all potential multibillion contributors. Combined, they should produce over $50 billion yearly. A significant mutual disarmament agreement with the Soviet Union could save many billions more. We can add to this additional billions from stiff penalties on industrial polluters and from savings on pork barrel projects, unmeritorious subsidies (shipping, agricultural) and on commuter and intercity highway projects that have already encouraged far more automobile traffic and congestion than we should tolerate. These should more than suffice. If they did not we could always go back to the tax levels that prevailed before the tax cuts of the 1960s.

There is no inflation in this scenario. But this is merely a by-product of something more important. What is at stake here is a happier society. It involves basically only some moderate transfers from those who can well afford it, and other transfers from wasteful to more rational and humane resource uses. For more than 40 years we have delayed. If we wait for a “right” time, a time free of grave national concerns or troubles, we will wait forever. It is only by our purposeful and constructive actions that the time can be made right. Like now. This is what the elections next fall, and in 1976, should be about.