Reform of the state abortion laws is not a popular cause even though these statutes result in extraordinary inhumanity when they are enforced, and lead to spurious medical practice when disregarded, as they commonly are. In practice, abortion is treated as illegal throughout the country unless the operation is undertaken to save the mother’s life. This has meant that zealous hospitals have refused to abort a 14-year-old girl impregnated by her father, a woman raped on the street by a man she had never seen, a mentally defective girl coerced into intercourse and in no position to take care of a child. In none of these instances were the lives of the prospective mothers in danger.

The very stringency of the laws probably has encouraged their violation. Each year between 200,000 and one million illegal abortions are performed in the United States, an estimated 90 percent of them by doctors. (Accurate statistics are scant, but doctors who make a study of the subject believe the probable incidence is closer to one million.) By contrast, an estimated 9,000 therapeutic abortions are performed legally in hospitals each year. In theory these are all carried out under the letter of the law, but in reality abortion prosecutions are unpopular and the decision whether or not to abort is left with the hospital. Their policies, while usually restrictive, are neither uniform nor just.

Medical justifications for abortion have declined. Advances in the treatment of pregnant women suffering from lung, kidney or heart conditions have meant that many now can be brought through pregnancy successfully, whereas in the 1930’s abortion might have been necessary to preserve their lives.

Some hospitals will abort for eugenic reasons, e.g. a woman who has German measles early in pregnancy. It has been amply demonstrated that in 15 percent or more of such cases, the child will suffer from congenital heart disease, blindness, or other malformation. On the other hand, the refusal of the Arizona courts to permit a hospital to abort Mrs. Sherri Finkbine after she had taken Thalidomide is a well-known instance of the opposition to abortion for eugenic reasons.

Abortions are more frequently granted for psychiatric reasons. Under the letter of the law, a psychiatrist must say or be prepared to say that the patient will commit suicide if she is refused an abortion. Since the incidence of suicide among pregnant women is very low, this seems a rash prediction for a scrupulous psychiatrist. (A medical examiner in New York City could not recall a single such suicide in a quarter century.)

In practice it is far easier for a woman with money to receive an abortion in a private hospital than it is for a woman without money to be aborted in a public hospital. In public hospitals officials are more prone to political pressures; in some, each abortion or attempted abortion must be reported immediately to the district attorney’s office. The emphasis is often on reducing the number of abortions each year, lest the hospital be known as an abortion mill. Catholic hospitals generally do not allow abortions to be performed. (An operation, however, is conceivable if the abortion should be the by-product of an operation to save the prospective mother’s life, i.e. the case of a malignant ovary.)

The cost of an illegal abortion fluctuates widely and depends on the qualifications of the doctor, the diligence of the police in applying the laws, and the time of pregnancy during which the abortion is sought. Present costs to the patient range between $350 and $1,500. A therapeutic abortion performed in a hospital might cost the patient $200 or slightly more. If the operation is performed before the end of the third month, it is a relatively simple and safe procedure known as dilation and curettage. As Dr. Alan Guttmacher, a leading gynecologist, describes it: The mouth of the womb is stretched open, after which a curette—a small instrument resembling a rake—is passed into the uterus and its pregnant contents scraped out. However, if the pregnancy has passed the third month a miniature Cesarian section is performed. In Sweden, abortion in these later stages is sometimes induced by injecting a salt solution through the abdominal wall.

A survey conducted between 1938-1955 of 5,293 white women by the Institute for Sex Research, founded by the late Dr. Kinsey, indicated that no more than 10 percent of 1,067 women who had abortions had taken drugs to induce them. The study of such drugs, they noted, has been avoided because of the moral implications, though it was evident it would not be difficult to develop effective and safe drugs, including some to be taken orally.

The impetus for reform of the laws thus far has stemmed from two major groups. One is the Planned Parenthood Federation of America, whose concern with birth control is long-standing. The American Law Institute, a select group of jurists, has adopted proposals for abortion reform as part of a model penal code. These proposals currently are embodied in amendments now pending in both the Minnesota and California legislatures. They would permit abortion in cases where pregnancy was the result of rape, incest, and in instances where it occurred in a minor or where it was obvious that the mother would give birth to a malformed child. The statutes would be additionally broadened to permit the operation should a prospective mother’s physical or mental health be “gravely” impaired by continued pregnancy. Two physicians would certify such conditions.

In neither state is the passage of these modest reforms likely, though in California a Los Angeles County grand jury called for reform. In New Hampshire where the state medical society had urged reform of the archaic abortion laws, both houses of the legislature voted last year over Catholic opposition for reform, only to have the bill vetoed by the Governor. In Illinois Catholic opposition to the abortion section of a model penal code was so strong that the section was dropped.

The American Medical Association seems to have established its position on abortion in 1859 when its House of Delegates approved a resolution condemning abortion except “as necessary for preserving the life of the mother and the child.” At that time, however, it was worried about the increasing frequency of criminal abortion practices and during the following decade adopted a series of strong resolutions condemning doctors who performed abortions and urged society to rid itself of this evil practice. When last heard from in 1908, the Delegates refused to authorize the creation of a committee to investigate the laws pertaining to criminal abortion. A sense of delicacy and expense have prevented anyone with the exception of Dr. Kinsey from collecting statistics on the incidence of criminal abortion. The federal government appears cowed in this as in most other areas of population control.

Then there are the churches. Roman Catholics regard abortion at any stage of pregnancy as a form of murder: life begins at the moment of conception. But this does not mean that Catholics are not aborted. There is every indication that they are, and in large numbers. Moreover, in various parts of Latin America, Catholic doctors have dispensed both birth control information and mechanical birth control devices to the population in order to reduce the vast numbers of women who fill the hospitals in various states of misery after their own attempts at abortion have failed.

Sanctity for the Chaste

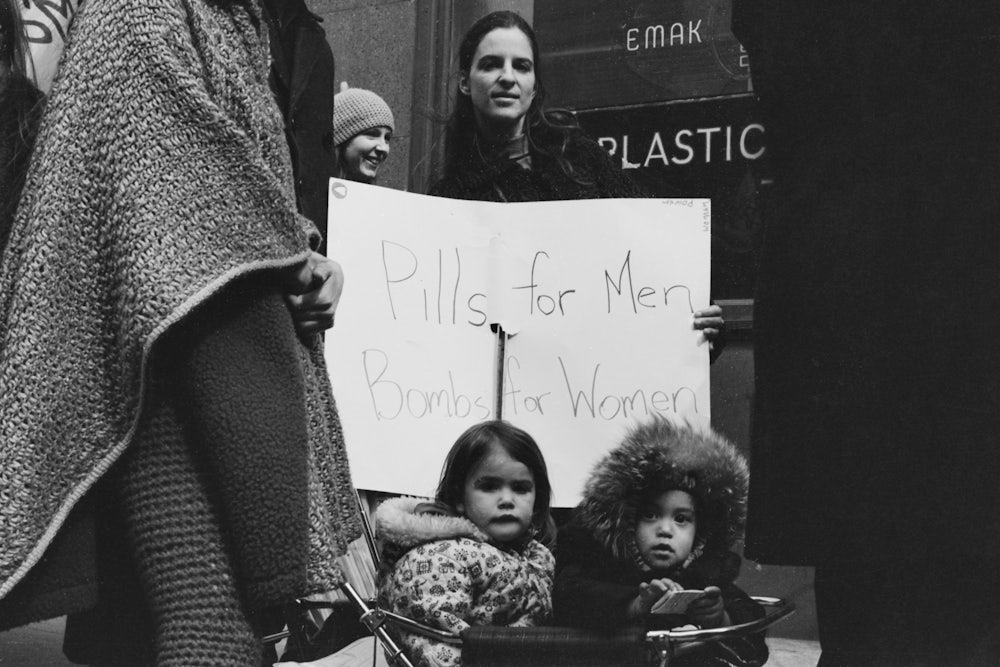

The opposition to abortion reform usually has less to do with religious dogma than with vaguely Puritanical traditions which influence Protestants. The practice, after all, is a white, middle-class phenomena, countenanced and paid for by the very people who make it a crime. The women of this group are left to stew in their own guilt. Their men take highly original views, never more contemporaneously expressed than by a young man quoted in the book. The Abortionist, by Dr. X. “Why don’t you get money from the man who is the father?” says Dr. X to an 18-year-old girl who straggles into his office pregnant and without cash. “I asked him,” she replied, “But he said, ‘Go to hell. You’re old enough to know the facts of life. It’s your problem’.” A variation was expressed in a cartoon in The New Statesman not long ago. A boy is talking to his sweetheart (obviously pregnant) at a coffee house. Says he, “Yeah, I know it’s mine, but I ain’t marrin’ no bird wot ain’t a virgin.”

One might expect a helping hand from the medical profession. Such is seldom the case. Ostensibly these doctors seek to protect their own skins from the public prosecutors. However, it seems far more probable that they abide by the AMA’s philosophy that modern medicine can best be practiced in the advanced circumstances of the Victorian era. By doing so, they deny many women legitimate medical counsel and, in effect, shunt them through the back door where they find other doctors who exploit them financially. These women must pay the medical profession several hundred million dollars a year to preserve its chaste veneer.

Society has adopted a somewhat more modern attitude toward abortion elsewhere in the world. In most Eastern European countries—which closely imitate the Soviet Union—abortion is legal on request through the third month of pregnancy, the safest period in which to abort. Since the mid-1950’s when this legislation was adopted, the numbers of legal abortions have grown markedly. (Most of the increase undoubtedly reflects the transfer of illegal abortions to a legal status.) In Hungary the number of abortions now exceeds the number of live births. The death rate from abortion operations is extremely low, in a 1957-58 period it amounted to 15 deaths in 269,000 abortion operations, according to statistics compiled by Dr. Christopher Tietze, Director of Research of the National Committee on Maternal Health. The announced purpose for legalizing abortion in Eastern Europe and in the Soviet Union was to abolish criminal practices, and to permit the prospective mother to make a decision as to whether or not she wanted the child.

It Costs $8.75 in Japan

Japan made abortion legal on request in 1948 for women less than three months pregnant, for the specific purpose of reducing the birth rate. As a result the rate has been halved. An estimated 1.7 million abortions are performed annually, slightly more than the 1.6 million births. There is little religious opposition to abortion in Japan. Shinto, for example, does not recognize the child as a living person until it has seen the light of day. Dr. Guttmacher learned in a recent trip to Japan that 20,000 doctors are licensed to abort, and the patient pays $8.75 for the operation, most of which can be retrieved through health insurance programs.

The Scandinavian countries have adopted abortion practices less restrictive than those of the United States, but far more limited in scope than either those of Japan or East Europe. In general abortion is permitted for reasons of life or health (social and economic considerations are taken into account in the definition of health); for congenital conditions including German measles and inherited diseases; and for various humanistic reasons, i.e. where pregnancy results from rape, incest or other violations of the penal code. The rate of abortions rose from seven per 1,000 in 1939, the year of legislation, to a peak of 70 per 1,000 in 1955. Since then they have declined to about 50 per 1,000. Abortions are permitted mid-way through pregnancy, and this contributes to the relatively larger death rate than that experienced in East Europe—66 per 100,000. A public health board, consisting of doctors, sociologists and social workers, among others, makes the decision for or against abortion in each individual case. These laws, however, have not substantially reduced the number of criminal abortions.

It seems likely that the United States will move, albeit slowly, in the direction of the Scandinavian laws. The idea of a hospital board deliberating and making the decision for or against abortion is gaining popularity. For one thing, it takes the pressure off a single doctor. If the state laws were broadened to permit abortion where the penal code was violated and in instances where the health of the mother was gravely threatened, such hospital boards would have considerably more latitude to judge. This would, however, necessitate the medical professions taking a somewhat broader view of health, which all too often seems to be interpreted where abortion is concerned to mean the mother’s sheer physical stamina to survive birth.

Even should these mild reforms be passed by some state legislatures, and the medical profession broaden its present limited perspectives, the incidence of illegal abortion is unlikely to decline unless the medical profession also adopts a more tolerant attitude toward birth control. And even then a decline is far from assured. We know perfectly well that young women have pre-marital sexual relations, and society encourages young married women to attempt to have families and careers at the same time. Such women finding themselves pregnant, will and do seek abortions, illegally if necessary. The emotional and psychological repercussions in certain instances are no doubt intense. Stories of the horrors of abortion, comprise a sizable body of literature. The Kinsey study showed, however, that three-quarters of the women interviewed who had had abortions reported no unfavorable after-effects. Social consequences were slightly more important among unmarried than among married.

At current estimates, one out of every four pregnancies in the United States is terminated by abortion. National figures of deaths due to abortion are not compiled, but it seems unlikely that these are high. Perhaps 100,000 illegal abortions are performed annually in New York City alone. Last year about 55 died in New York from abortion; 8,000 patients were treated in city hospitals for self-induced, incomplete abortions. (These often are begun with coat hangers, nails, or other objects which women jab into themselves.) The deaths, together with the large number of women hospitalized, obviously constitute a large public health problem, which New York has been meeting in several ways. The police have taken a slightly stiffer attitude toward abortionists, and carried out several well publicized crack-downs. The Health Department is considering putting out flyers on the dangers arising from self-induced abortion, particularly in the slum areas of East Harlem and the Lower East Side. But as one doctor said, “You can’t tell a girl she’s going to be crippled for life from an abortion when all she wants is out.” It is far more feasible and kinder to pass the word about hospitals in Puerto Rico or elsewhere, where abortions can be performed cheaply and cleanly. New York has further complicated its own problems by insisting that Welfare Department workers say nothing about birth control to families unless such information is requested.

It seems highly unlikely that many women seek abortion frivolously. They do so as a final, desperate measure of birth control. Yet the subject of birth control is greeted with fright in the counsels of government, manifested most lately by jibberish from the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, which spent an entire year rewriting a simple bibliography of population control research so that it would not offend anyone. Yet the government is in an excellent position to further the study of birth control and assist in the dissemination of birth control information and devices (to those who desire them) through financial support to clinics across the country. It could sponsor studies to determine the incidence, cause and effect of abortion in the country. It can scarcely expect volunteers from the National Service Corps to function as social workers in New York City and elsewhere, without facing up to these problems.

It is probably too much to hope that the medical profession can be lured off the fence in support of abortion reform in California and Minnesota or elsewhere. However, if the state legislators could screw up their courage, the few doctors who must deal with this problem might feel encouraged to put up a stiffer fight in their hospitals and within the profession. New legislation in the states might also mean that the few decent and reputable abortionists who now practice would be permitted to do so in a freer atmosphere, where they might perform a medical service to that portion of the population which desires it. That they should be packed off to jail by a minority applying anachronistic laws is intolerable. For there is nothing remotely resembling a consensus within this society against the practice of abortion. Indeed, it appears there are a large number of people in favor of it, when other measures of birth control have failed. With the federal government’s head buried deep in the sand, with the medical profession mired in the 19th Century, one can hope for little more.