It does not augur well when a culture’s richest and most powerful men begin musing in public about whether a better life might await them on some otherworld colony. If you’ve spent all or even some of this last year living here on earth, it’s easy enough to understand the temptation, but when the lords of this particular realm are indulging these fantasies—think of Elon Musk’s aspiration to build a city on Mars over which he might preside like a more epic and meme-forward version of Total Recall’s Cohaagen—it gives the impression that they are more or less done with this used-up planet and everyone on it. Imagine Watchmen’s Dr. Manhattan in high isolation on the moon, a god grown tired of his rude and ravening and hungry lessers, except now he’s also really into NFTs and tax avoidance. It’s all ominous, almost poignantly oafish, and sociopathic in the deeply corny ways that we have come to expect from our superclass of tech billionaires. But there is an even worse escape than all of this.

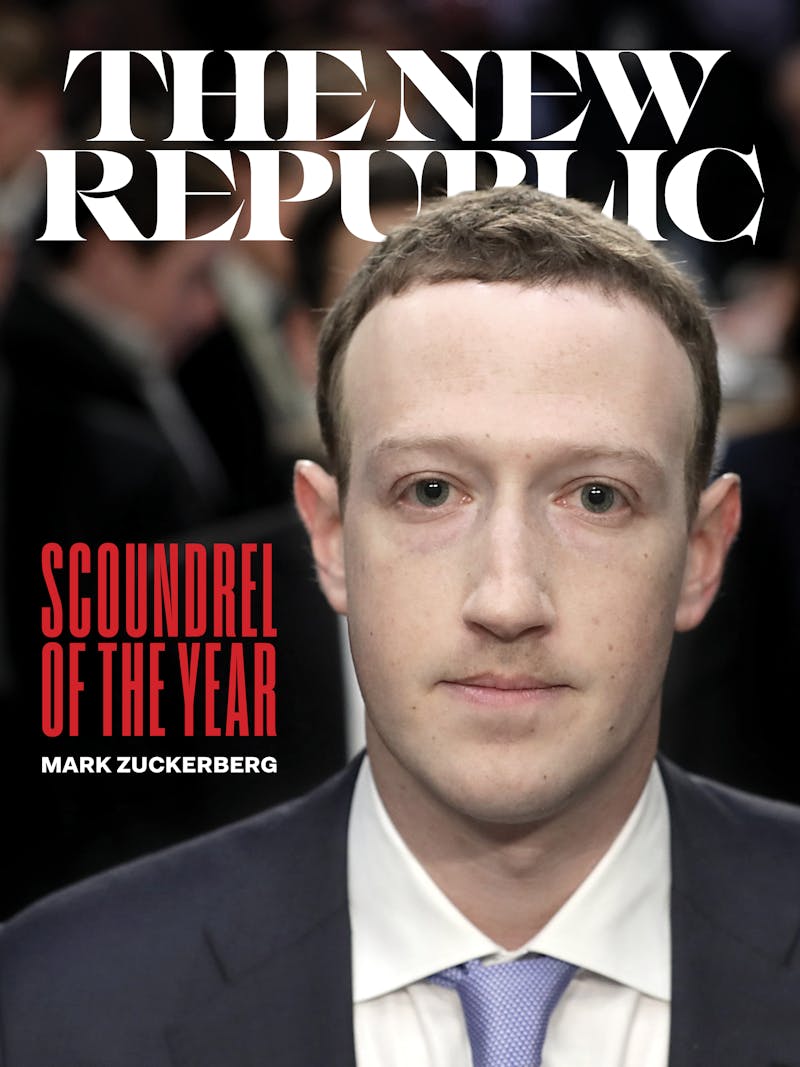

In October, Facebook Founder Mark Zuckerberg announced that his company would not just be changing its name to Meta—I will continue to call it Facebook here, as I assume will everyone else—but broadening its ambitions to encompass becoming a virtual reality community in which people might work, play, spend, and live. “I believe the metaverse is the next chapter for the internet,” Zuckerberg said in announcing this news. “And it’s the next chapter for our company, too.”

To a certain extent this is just how Silicon Valley’s apex-predator types talk about things now. Because the Web3 fripperies that intrigue them—think of the speculative-unto-grifty froth at the confluence of cryptocurrencies and NFTs and virtual reality and other such ostensibly decentralized, ostensibly liberative online aspirations—are intriguing to them, they believe that those fripperies must therefore be the future of something or other. And, to a certain extent, the outsize power and wealth afforded them by their success in this version of the internet guarantees that they’re at least a little bit right, if only because anything with that much influence and raw money behind it is unlikely to go away simply because normal people do not find it very appealing. In matters like this a little bit of brute force, when exerted by a class of sufficiently forceful brutes, can go a very long way.

But it is worth mentioning that the metaverse as Mark Zuckerberg envisions it is just not a very appealing idea, and only partially because it is Zuckerberg himself explaining it. The concept that Zuckerberg laid out in a protracted and pyrotechnically cringy presentation seems so thoroughly innocent of any idea of what people actually want to do in their nonvirtual lives, let alone in their virtual ones. “This is the Facebook ‘metaverse,’” Max Read wrote in his newsletter. “Using goggles made by Facebook subsidiary Oculus, you enter the Facebook-hosted V.R. metaverse, where you can meet your friends at a V.R. bar, play V.R. board games, go to V.R. meetings for your V.R. job, get summoned into a V.R. conference room to get V.R. furloughed by your V.R. boss and a V.R. human-resources representative.” To be fair, Zuckerberg makes clear in his presentation that metaverse users will also be able to look like a cartoon bear while doing all of these things, if they so choose.

As John Herrman noted in The New York Times, the reason to be skeptical about this endeavor is not that people don’t want to do some or all of the stuff that Zuckerberg talks about in strained tones of wonder and whimsy. Whether in terms of speculating on cryptocurrencies or gaming with a V.R. headset or just clocking into a virtual workplace, people are absolutely already doing all those things, albeit sometimes more happily than others. It is not even the question of why anyone would entrust the design and implementation of the future to Facebook, which has made the world infinitely dumber, uglier, and worse in a number of obvious and inescapable ways, and is a miserable website to use to boot. That is a really good question, though, if only because it is just extremely difficult to imagine someone choosing to work and live inside the website that convinced their grandparents that the germ theory of disease was a hoax. But what really rankles is that it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter that this vision of the future is extractive, joyless, and dull; that the smug cretins who got rich off the platforms that this new decentralized movement is supposedly leaving behind are also leading the supposed successor movement doesn’t matter either. This push to transcend the world that Facebook has befouled and create a new, virtual one can be read in a sense as a response to the 10,000-page Facebook Papers leak, which demonstrated both the extent to which Zuckerberg’s own criminal indifference and Facebook’s inability to police its own sprawl have made the site a malignant metastatic force in countries around the world. Again, it doesn’t matter.

This is the taunt implicit in everything Zuckerberg does at this point in his reign. Here is a man who got unconscionably rich off the worst website that has ever existed, a website that has broken brains on a scale previously unimaginable in human history, and here is his stupendously wack vision for the future—and everyone is just going to have to deal with it. There are many things to abhor about Mark Zuckerberg and his works, but the fundamental mediocrity of it all—the lack of vision, the absence of any moral sense or shame, the inability and unwillingness not just to fix but even reckon with the dangerous and ungovernable thing he’s made—is what feels both most egregious and most of this moment. It is embarrassing and not a little enraging to realize that you are subject to the whims of an amoral and incurious capitalist posing as a visionary optimist. It is especially humiliating when the all-bestriding and inevitable figure in question is such a dim, dull nullity.

It seems important to mention that Facebook is not just a bad website, but a company that has shown itself willing to do the wrong thing whenever and wherever given a choice. Facebook was not the first and is not the only company to tell wild lies to advance its own ends, but few companies have done it bigger or suffered less for it. Facebook also did not invent a politics grounded in unreasoning spite and toddler-grade oppositional defiance and relentless resentful signaling; Americans did that all on their own, with some crucial late help from one family of reactionary Australian media types. But Facebook did create an algorithm that valued that style of grievance above all others, which pulled users along behind in turn. In the United States, the culture wanders, hunted and lost, through the virtual and nonvirtual wreckage those decisions made, without even the armor afforded by a V.R. bear costume. Abroad, where Facebook has been criminally indifferent at best and actively complicit at worst in abetting the spread of dangerous medical misinformation and genocidal rhetoric, the damage has been infinitely worse.

Americans represent only about 10 percent of Facebook’s users, but nearly 85 percent of the efforts that the company has put toward stemming the spread of misinformation has been focused on the U.S. In early December, NBC News’ Brandy Zadrozny reported that the specious pseudo-documentary Plandemic, which Facebook more or less succeeded in banning in the U.S. after it spread widely on the platform in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, was not only still easy to find on Facebook in Romania, but had been viewed on the platform more than 800,000 times in a country that, with a 40 percent vaccination rate, significantly lags behind the rest of Europe. Massive class action lawsuits filed against Facebook in California and the United Kingdom in December on behalf of Rohingya refugees living in the U.S. and the rest of the world, respectively, claimed that Facebook’s presence in Myanmar after 2011 was a “substantial cause, and perpetuation of, the eventual Rohingya genocide” that began in that country in 2013, and which Facebook effectively ignored despite multiple warnings from inside and outside of the company.

“In the face of this knowledge, and possessing the tools to stop it, it simply kept marching forward,” the California complaint reads. “The undeniable reality is that Facebook’s growth, fueled by hate, division, and misinformation, has left hundreds of thousands of devastated Rohingya lives in its wake.” It is all bad, but the common denominator is that Facebook, which is obsessed with its own internal data and metrics, always knew what was happening and why and always blithely didn’t care. Despite the ongoing human rights crisis in Myanmar and the attendant international outcry, Facebook didn’t even hire content moderators fluent in local languages until 2018.

Facebook, as a company that is hyperfixated on growth and its own bespoke engagement standards, makes the decisions it makes because those decisions make important numbers go up. When it allows Vietnam’s government to censor dissidents on the site, it is because doing business in Vietnam makes revenues go up. When it permits incitation-oriented hate speech to exist on the site, whether in relatively minor markets like Myanmar or enormous ones like India, it is because it has noticed that keeping readers enraged also keeps them engaged, and because that engagement (Facebook’s current internal term of art for this, coined by Zuckerberg himself, is the suitably dystopian “meaningful social interaction”) is what the company values. When Facebook gooses its algorithm such that it favors and promotes that kind of speech, it is for the same reason. These are all profoundly vile, but none could remotely be described as a mistake. Every one of them is a choice, and the person who makes the choices at Facebook is Mark Zuckerberg.

So when Zuckerberg tells weird lies about all this in front of the U.S. Senate—when he claims that 94 percent of hate speech was scrubbed from the site before anyone ever saw it, for instance, despite internal metrics that show only 5 percent was removed at all—it is because he believes he can get away with it. There is no one who could meaningfully tell him no, both because he owns 58 percent of the company’s voting shares and is also the chairman of its board, but also because Facebook is organized such that he effectively has the final say on every decision the company makes; no other company this size invests so much formal or informal power in one person. It’s a terrible thing to say about someone, but Mark Zuckerberg really is Facebook. It shows.

The most fundamental problem with Facebook is that it does not have, and never really has had, any idea how to do any of this. It certainly has no real sense of how to be the kind of unimaginably vast global institution—the site claims 3.51 billion monthly users—that it very quickly became, and is in fact absolutely terrible at every aspect of being that site beyond the crucial Making Money Doing It element. All those monthly users interacting with all the ads that choke Facebook’s timeline and clutter its margins and blunder unbidden into every available space generate a lot of money for the company. This presumably helps soothe the realization that the core product itself is both absolutely loathsome and widely loathed—confusing and unpleasant to use, governed by an algorithm that seems to have been designed to make the experience of being on the site as unpleasant as possible, and increasingly the province of the shut-ins, kooks, quacks, grifters, and the dreaded Gun Uncle. Facebook has been pretty much exactly that bad for many years, in fact. It is, in every sense, the website that exists at the exact midpoint of Everyone Can Share Anything With Anyone and “doing the logistical and marketing scutwork for genocidaires and authoritarians and local sociopaths.” It’s awful.

More than that, it could only be awful. Facebook, which talks about itself as The Sharing Place but is driven by the incentives of the cheesy surveillance and value-neutral click-chasing and overwhelming economic leverage and relentlessly cynical avarice that make it profitable, could never and would never become anything but this, and could never and would never care about any of the damage it does. It will respond to a certain level of opprobrium or shame, albeit in qualified ways and at the last possible moment; if there were any sense that the regulatory or governmental arms of the U.S. government might be able or just willing to hold it to account, Facebook might theoretically respond to that. What that has looked like, for years, is Zuckerberg putting on a neat suit and sitting in front of various plump Senate grandees who take turns asking him to help them unlock their phones and accusing him of being very unfair to Diamond and Silk. The senators change, but Zuckerberg and his answers stay the same.

It is fraudulent and irresponsible and quite probably criminal in ways that reflect its co-founder and ruling lord, but what Facebook most has in common with Zuckerberg is that it sucks—not just in the sense that it is lame and bad. Even if you leave aside its authentic crimes against humanity, Facebook is still a machine built to turn lonely elderly relatives into blood and soil fascists; a haunted satellite that intermittently farts out the dispiriting opinions of random former high school classmates; a relentlessly tweaked, irredeemably borked newsfeed that shoves variously viral idiocies and advertisements at users with the horny and unlovable insistence of a frotteur moving through a crowded subway car.

The funny part is that Facebook isn’t even good at being that. Sure, the numbers go up, but the people that Facebook and Zuckerberg are trying to court with their metaverse initiative—younger people in general, but primarily the elusive creator who has little use for Facebook’s towering and overbearing uncoolness—know what Facebook is. They know that Zuckerberg’s metaverse is just a mall-shaped prison through which all of humanity would wander while being pelted with advertisements, slurs, and dumb, garish lies. In a nation functioning as poorly and unaccountably as ours, even petty and fraudulent titans like Zuckerberg can come to seem permanent; it is part of the citizenry’s broader terms of service that every now and then the accumulated consequences of their failures simply come rushing downhill at us like an unpleasantly fragrant mudslide. From that vantage point, after all this, it is impossible to perceive Mark Zuckerberg’s invitation to join him in a second universe as anything but a taunt. Look what he’s done to this one.