Much like the previous year, 2021 was a constant deluge of news: much of it bad (failed insurrection, the persistence of a deadly pandemic, etc.), some of it good (vaccines, boosters, etc.), and almost all of it overwhelming. It was a year of grim milestones, such that the phrase “grim milestone” itself became a cliché incapable of capturing the breathtaking devastation wrought by phenomena such as the pandemic and natural disasters.

The presence of the pandemic in our lives likely kept one such horrifying development off the front page: This year’s surge in drug overdose deaths, which for the first time climbed past 100,000 in the 12-month period ending in April 2021. The numbers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics, released in November, articulate a devastating new record of predicted deaths that came amid Covid-19’s ravages. The provisional number was a 28.5 percent increase from the 78,000 deaths in the prior year, with 75 percent of overdose deaths caused by opioids, mostly of the synthetic variety. As of early December, the predicted number of deaths for the 12-month period ending in May 2021 was slightly lower, but still above the 100,000 mark. (The number of reported deaths was slightly under 100,000 for both periods of time, but according to the NCHS, these numbers were underreported due to incomplete data.)

“I was expecting that the numbers would look bad,” said Dr. Andrew Kolodny, the medical director of the Opioid Policy Research Collaborative at Brandeis University’s Heller School for Social Policy and Management. “But it got even worse than I anticipated. Significantly worse.”

The 12-month period between May 2020 and April 2021 coincided with the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, a time that saw more people lose access to treatment as well as an increase in patients reporting mental health issues. A separate report released in July found that life expectancy in the United States had decreased in the single largest one-year drop since World War II, a decline fueled by the combination of Covid-19 and deaths from accidents or unintentional injuries, one-third of which were drug overdoses. (Data released in December confirmed the decrease in life expectancy of 1.8 years between 2019 and 2020, with coronavirus replacing deaths from unintentional injuries as the third leading cause of death in 2020.)

Prior to the arrival of the coronavirus, the opioid crisis had the country in its grip. Opioid deaths increased by 200 percent between 2000 and 2014; a brief decrease in deaths in 2018 was offset by a surge the following year. The data released in November showed that there were more overdose deaths from synthetic opioids than there were overdose deaths from all drugs in 2016.

West Virginia had the highest rate of deaths, with the District of Columbia coming in second. Although Vermont had a comparatively smaller quantity of deaths, it had the biggest increase in overdose deaths, at 70 percent, with West Virginia clocking in behind it.

Kolodny told The New Republic in a November interview that most people who died due to overdoses were addicted to opiates and that the devastation of addiction had been exacerbated by the pressures of the pandemic. In the early weeks of the pandemic, the stress of isolation and the potential loss of support offered by 12-step programs could have encouraged relapses among people who were in remission; moreover, it may have been more difficult for people still in the throes of addiction to receive necessary treatment.

Congress made efforts to address the opioid crisis, but it was simply not at the top of the legislative to-do list this year. The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022, which was signed by President Joe Biden on Monday, includes an amendment to identify countries that are major producers or distributors of illicit fentanyl and withhold some foreign aid unless they classify the drug and crack down on traffickers within their borders. Democratic Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Republican Senator Rob Portman of Ohio, each representing a state the opioid crisis has hit disproportionately hard, also recently reintroduced a bipartisan bill this year to permanently “schedule,” or classify, illicit fentanyl, allowing federal law enforcement to bring action against drug manufacturers and distributors.

Earlier this month, several Democrats reintroduced the Comprehensive Addiction Resources Emergency Act, which would provide $125 billion over 10 years to address substance use, with targeted funding for states, cities, and counties, as well as money for research and training.

But Congress has not fulfilled Biden’s budget request or passed any appropriations measures, instead opting to pass a stopgap measure funding the government at current levels through mid-February. This is due to a disagreement between Democrats and Republicans over how certain programs should be funded—a predictable annual debate. But the lack of action does factor into the effort to address the epidemic of opioid-related deaths. The president’s budget request included nearly $11 billion in funding to address the crisis, and the Senate appropriations bills introduced this year included a $500 million increase for State Opioid Response Grants. (In October, the House passed a bipartisan bill reauthorizing the State Opioid Response Grants, but it has not yet been considered in the Senate.)

House Appropriations Committee Chair Rosa DeLauro has called on Republicans to engage in negotiations on an omnibus appropriations bill that will address the opioid crisis, among other critical priorities. “This is a big issue that people are facing in their lives,” DeLauro said about the crisis in response to a question from The New Republic in November. “Let’s get to the table, let’s talk. Because this is critical.”

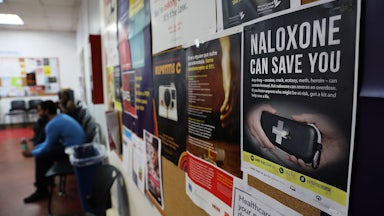

The White House has also introduced a “model law” for states to expand access to naloxone, which can be used to counteract the effects of an opioid overdose. However, Kolodny argued that expanding access to naloxone doesn’t address the root of the problem. “The opioid crisis is an epidemic of people with opioid addiction, a preventable and treatable condition,” Kolodny said. He also said that there needs to be a regular funding stream to address the crisis, not just one-time appropriations that leave states in the lurch when the money runs out. “We need new funding streams, or at least a commitment to long-term funding, if we’re really going to build out the system we need so that people can much more easily get treated.”

Members of Congress have recently introduced legislation that would address the underlying cause of the crisis, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, or CARA, 3.0. Congress passed CARA in 2016 and legislation including several provisions from CARA 2.0 in 2018. The new legislation includes policy changes and an additional $785 million in funding for prevention, treatment, and recovery services.

“We’ve got to go all in,” Representative Tim Ryan, a cosponsor of CARA 3.0, told The New Republic in November. “I didn’t think there was enough money in the first one for treatment and recovery … It’s got to be a comprehensive approach.”

Without additional funding for treatment, the opioid crisis will only worsen. This does not just mean additional rehab beds, Kolodny said, but long-term outpatient programs with access to treatments like buprenorphine, which is prescribed to combat opioid use disorder. Medical practitioners currently still need federal permission to prescribe buprenorphine, limiting the number of physicians who can provide it. (Members of Congress have introduced a bipartisan bill to remove the requirement to seek permission in order to prescribe buprenorphine, but it has not yet been acted upon in either chamber.)

“That has to be easier for people to get than it is to buy heroin or prescription opioids or fentanyl,” Kolodny said. “Buying a bag of dope is inexpensive and easy. But accessing effective treatment is expensive and complicated.”