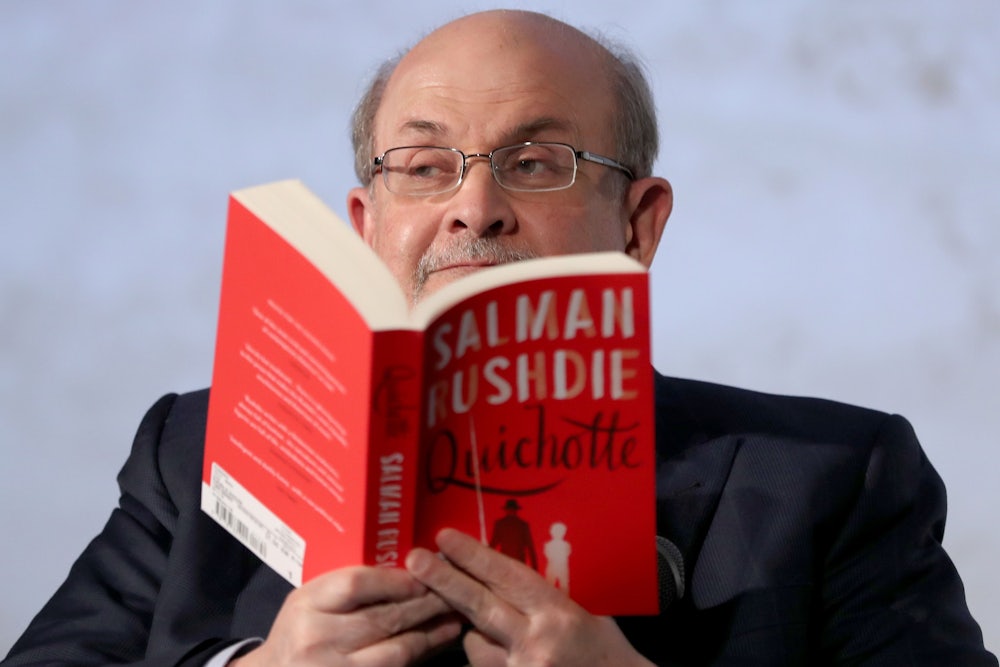

The novelist Salman Rushdie was repeatedly stabbed on Friday as he was about to give a lecture at an education center in western New York. The 24-year-old suspect’s motive is unclear, police say, but we do know the attack was premeditated. We also know that since 1989, Rushdie has been living under a fatwa, issued by the late Supreme Leader of Iran Ayatollah Khomeini, calling for the author’s murder for writing The Satanic Verses—a decree that has left a trail of blood and destruction. The attacker has expressed affinities for Shia extremism and the Iranian regime.

But to certain American writers who have made their name by imagining the death of free speech at every turn, the real cause of the horrific attack was clear: cancel culture.

Writing in The Atlantic, Graeme Wood wondered “if some of us are more Khomeini than we’d like to admit.” Referencing former President Jimmy Carter’s disgraceful 1989 op-ed that soft-pedaled the fatwa, “Rushdie’s Book is an Insult,” Wood lamented that “over the past two decades, our culture has become Carterized. We have conceded moral authority to howling mobs, and the louder the howls, the more we have agreed that the howls were worth heeding.” In a similar vein, Bari Weiss argued on her Substack that “it is the indulgence and cowardice of the words are violence crowd that has empowered” religious fanatics like Rushdie’s alleged attacker. The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik expressed concern over “the idea—which has sprung to dangerous new life in America as much on the progressive as the theocratic side of the argument—that words are equal to actions.” And Cathy Young distilled this argument into perhaps its purest form, writing on Twitter that “once you’ve decided that dissenting speech amounts to ‘harm’ and ‘violence,’ you’re halfway to defending stabbings.”

Given the above commentary, you would think that many on the left today were responding to the attack in Carter-esque fashion. But you will find no such examples in the writings above, and in fact you will be hard-pressed to find any online whatsoever. The response from the left, appropriately, has been horror, solidarity, and unqualified condemnation of the attack. That these writers nonetheless insist on connecting Rushdie’s stabbing with America’s comparatively quaint free speech debates—while also failing to make the obvious comparison between Rushdie and America’s real cancel culture, which is conservatives’ zeal for book-banning—exposes their blinkered thinking.

To read these pieces is to enter a maze of false equivalences and sweeping claims presented without evidence. Take, for example, Weiss’s assertion that “of course it is 2022 that the Islamists finally get a knife into Salman Rushdie. Of course it is now, when words are literally violence and J.K. Rowling literally puts trans lives in danger and even talking about anything that might offend anyone means you are literally arguing I shouldn’t exist.” The words “of course” are doing a lot of work here to combine two entirely different phenomena. On the one hand, we have a physical attack on an author who has long been explicitly menaced by a foreign power—threats taken seriously by the British government, which provided security for him over many years. On the other hand, we have criticism by individuals of J.K. Rowling’s stated beliefs. How is this even remotely similar to a state-backed call to violence? And is there any reason to think that Rushdie’s attacker was in any way tuned in to such debates?

Wood speculates that today “nobody would publish [The Satanic Verses], because sensitivity readers would notice the theological delicacy of the book’s title and plot.” That’s certainly within the realm of imagination, but we don’t need to reach for hypotheticals when Margaret Atwood’s classic novel depicting a theocratic dystopia, The Handmaid’s Tale, is already banned in nine school districts across four states, or Alison Bechdel’s acclaimed graphic memoir, Fun Home, is banned in five districts in four states. The sensitivity readers are already here, in our legislatures and school boards, and they are not bothered in the slightest with the concerns of the so-called politically correct left.

Gopnik likewise predicts that “efforts will be made, are bound to be made, to somehow equalize or level the acts of Rushdie and his tormentors and would-be executioners, to imply that though somehow the insult to Islam might have been misunderstood or overstated, still one has to see the insult from the point of view of the insulted.” Again, we are left to wonder why the commitment to such a twisted hypothetical amid a national wave of calculated attacks—mostly verbal, but sometimes physical—on teachers for daring to teach fiction such as Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (banned in two districts in Oklahoma) or Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner (banned in four districts across Florida and Texas)?

If you want to place the attack on Rushdie into a U.S. political context, it’s the rise in legislation to ban books from schools and local libraries that should most concern you. PEN America’s recent Index of School Book Bans lists more than 1,100 books banned from 86 school districts across 26 states. The most common themes among the banned books are discussions of race in U.S. history and LGBTQ+ identities. At the forefront of the national book-banning charge, you will not find progressives or offended college students, but conservative legislators intent on purging from schools and libraries content that threatens their political and religious sensibilities. Religious justifications have been central to conservative book-banning efforts.

The recent, well-documented surge of attempts by the religious right to ban books—not the moral panic over “cancel culture” or the “words are violence crowd”—is the correct context in which to understand the ways America might fail to protect current and future writers as it failed to protect Rushdie last Friday. Americans are not actually so deluded as to think there’s no difference between a claim that speech is offensive or causes harm and a courageous author facing an attempt on his life for his speech. We have not lost sight of authoritarian efforts, backed by state power and the credible threat of physical violence, to make us wary of what we say. The banning of books is not a figurative matter in contemporary America. It’s not like the censorship of another time, place, or regime; it’s the censorship we actually have.

For these reasons, efforts to explain the attack on Rushdie in the relatively trivial terms of the culture wars are at best tendentious, at worst a harmful distraction from the real threat. Once the state carves out a shifting, unbounded category of books it deems blasphemous, obscene, or seditious, and codifies such viewpoints in law, the state is creating the conditions for violent responses to speech. The fatwa against Rushdie is a de facto book ban, imposed by an authoritarian regime based on a sense that Rushdie’s novel, and novels like it, are blasphemous and punishable by death; it aims to cow people as well as educational and cultural institutions—schools, libraries, bookstores, printing presses—from having any connection with the book. Fortunately, at present, we’re missing the “punishable by death” part of the equation, though the organizers of Drag Queen Story Hour have come under attack from violent right wing agitators like the Proud Boys.

The U.S. political climate is now extremely volatile, with concerted efforts among conservative religious propagandists to justify book banning by portraying the discussion of banned content as a form of sexual perversion, and the authors of banned books, and the teachers teaching them, as “groomers” or pedophiles. The objective in so doing is to frame a class of people, and associated ideas, as outside the bounds and protections of humanity, or as worthy of contempt or disgust. Book-banning legislation formally sanctions such a worldview, endangering teachers, with the Justice Department now having to address threats of violence against teachers and school personnel. Being a vigilant, good-faith defender of free expression thus means, among other things, putting the decadence of culture-warring in perspective when real—not figurative—authoritarianism is in play.