Along with hundreds of other medical students, I sat rapt as Dr. Anthony Fauci, who had led the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases since before I was born, shared a series of slides that led to a single, inexorable conclusion: We didn’t know when or where, but there would likely be a major pandemic in our lifetimes. This was 2008, and Fauci had long since established himself as the single most respected infectious disease expert in the world.

Fast forward 14 years, and that pandemic has come to pass. Fauci understood that as new pathogens appeared more frequently, it became increasingly likely that one would emerge with the rare set of capacities for pandemic spread—and that it would drive our public health and health care systems to the brink.

What he probably did not—could not—understand was how that pathogen would convulse our politics. After all, Fauci, who announced on Monday that he’s retiring in December, is a relic of an era when government service transcended partisan warfare. The reign of President Trump ended that era—to many Republicans today, the government is just a tool to exact revenge on political enemies—and Fauci’s departure from NIAID shows why we should fear what comes next.

Fauci graduated from Cornell’s Medical College, ranked first in his class, in 1966. He finished his residency there a few years later. Rather than start a lucrative medical practice or ply his trade for a pharmaceutical corporation, he went straight to government service at NIAID, where he worked his way up to director in 1984—and has held the post ever since.

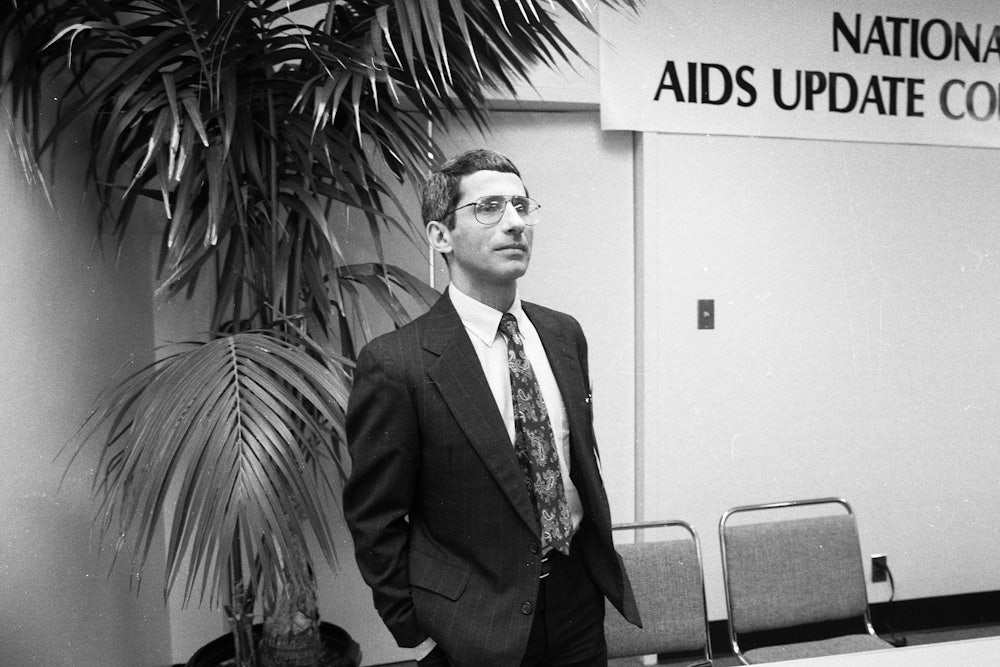

Covid-19 wasn’t Fauci’s first political rodeo. He led the institute through the HIV/AIDS crisis, where he was caught between the Reagan White House’s visceral anti-science bent and their disdain for the gay community, and a newly activated AIDS movement in the form of ACT UP, an organization of gay men dedicated to forcing urgency in the government and corporate responses to the epidemic. ACT UP protested the NIAID’s campus under slogans like “NIH, you can’t hide, we charge you with genocide.” Rather than reflexively oppose them, Fauci took their protest to heart. He recognized the unique perspective gay men had on the disease—and the fact that it could improve science and the epidemic response as a result. After attending an ACT UP meeting in 1989, he befriended the movement’s leaders. Together, they served as a critical conduit to enlist ACT UP as a trusted partner in NIAID decisions.

Since then, Fauci has cemented himself as the most trusted voice on emerging infectious diseases, at home and abroad—from SARS to Ebola to Zika. His scientific leadership of the arm of the National Institutes of Health dedicated to researching and developing vaccines and treatments for these diseases has earned him the admiration and trust of scientific and medical experts. But he also had a penchant for public communication, combining the fact-driven directness of a scientist, the calm and concision of a spokesman, and a politician’s innate ability to read his audience.

And yet, Fauci remained fiercely apolitical. Indeed, he held the same role under seven presidents—dating all the way back to Reagan. In 2008, President George W. Bush awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. But like many of the best things about government, Fauci was no match for the Trump era.

In early days of the pandemic, Fauci appeared across every major news outlet—but also directly contradicted a president who, at one point, seriously raised the idea of injecting bleach. He was thus adored by many Americans: There were Fauci votive candles, Christmas ornaments, and socks. But on the right, “fire Fauci” became a mantra of the Covid deniers—and even the name of legislation proposed by Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene. It is now a plank of the MAGA-possessed GOP that Fauci should be investigated and prosecuted for … well, it’s not exactly clear why, unless you believe the outlandish conspiracy theories.

The demonization of Fauci is about more than one man. It’s the ultimate triumph of the right’s politics of grievance and lies. There’s only one party that still believes in a politics of efficient, effective government, and we’re all the worse for it.

In December, when Fauci retires, the federal government will have lost one of the ablest public health professionals in its ranks. His example should be an inspiration to the next generation of the best and brightest—in public health and beyond—to serve their fellow citizens through government. But it may be just the opposite: The next generation could look at the way he has been vilified for his service and conclude that collecting a government salary to publicly debate craven halfwits over obvious truths simply isn’t worth it. In short, we may never benefit from someone like Fauci in public service again. And, that, perhaps, is the greatest loss.