In the past few months, a select group of Republicans received glossy booklets from Florida Senator Rick Scott, who currently serves as the chairman of the GOP’s Senate campaign arm. The 15-page pamphlet is a glossy articulation of Scott’s policy stances, which extend beyond the 2022 campaign trail to touch on immigration, “color blind equality,” religious liberty, “America First,” and “economy/growth.” It is, essentially, a rehash of Scott’s February “11 point plan to rescue America,” which on his website has now been plumped up to 12 points.

Scott’s booklet has reinforced the impression among many in Beltway circles that the Florida senator is gearing up to run for president. Within the party, Scott’s critics gripe that he’s been so focused on laying the groundwork toward a presidential run that he’s cashing in on his credentials as National Republican Senatorial Committee chairman to further his own ambitions ahead of the party’s.

Scott’s spit-shined policy manifesto, which he’s revived during the final months of the midterm cycle, isn’t the only thing that’s grabbed the attention of these critics. They also point to NRSC campaign ads airing across the country that feature just Scott on camera, rather than the Senate nominees the party wants to boost or Scott alongside such a Senate nominee. One ad, for instance, is a straight-to-camera shot of Scott urging supporters to sign a petition to oppose an election reform bill that Scott said was about “legalizing election fraud.”

NRSC Communications Director Chris Hartline said in an email that the videos Scott was in were “straight to camera fundraising videos, as every chairman of every committee does and has done since video was invented. And we do them with the Chairman, other Senators, other prominent Republicans, anyone who will help us raise money.”

In September, Scott is also doing the sort of thing that earns you a heaping helping of presidential speculation: He is co-headlining an event in Iowa—in this case for Mariannette Miller-Meeks, a member of the House who is running for reelection—alongside Governor Kim Reynolds. The event has been advertised.

That Scott harbors presidential aspirations is not exactly a secret among Republicans. Nor is Scott the first NRSC chair to have such ambitions. But the obvious way Scott has prioritized his future plans has cast a shadow on all of the NRSC’s moves this cycle. “‘Rick Scott for President’ has sort of antagonized a lot of these issues,” a former top NRSC staffer said.

Scott’s tenure as NRSC chair has fostered criticism outside of the 2024 presidential speculation (because, let’s be honest, every politician is running for president until they aren’t). The list of unforced errors by the NRSC is not small. There was Scott’s oddly timed vacation to Italy in August, just a few months before the midterm elections. Strategists argue that the committee is trying to expand its map of competitive races by investing resources in more long-shot races like Washington State or Colorado. They also complain that the NRSC sank $21 million into a quixotic text-messaging project.

“We’re going for reach states so he can be a hero. But you gotta protect what you have,” a former top Republican Senate staffer said.

As of the end of July, the NRSC reported having $23,165,628. By comparison the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee reported having $54,144,546. Some Republicans in Washington have adopted a gloomy outlook to Senate fundraising.

In August, Scott was one of the headliners at a fundraiser on Nantucket, alongside the Republican nominees for Senate in Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. It’s not unusual for a committee chair to co-headline a fundraiser along with Senate candidates, but in August, voters and donors are usually more focused on vacation (as Scott was when he slipped off to Italy) than statewide races.

The feeling coming out of the fundraiser was mixed. It yielded over $100,000. One of the candidates in attendance wondered why he even came if his share of the event was only about $25,000, according to two Republicans with knowledge of the fundraising event. Of the 41 people at the reception, only 16 people went to the dinner afterward, including the fundraiser’s VIPs (J.D. Vance, Hershel Walker, Dr. Oz, and Ted Budd), according to those with knowledge of the event. Planners for the fundraiser expected about 50 attendees. (Another attendee of the fundraiser disputed this characterization and said the turnout was good.)

In the last few weeks, the NRSC has been in a defensive posture over reports that it’s cutting spending in winnable states. The New York Times reported the NRSC was cutting millions of dollars of advertising in Arizona, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Politico followed up with reporting that said the committee cut $13.5 million. But just this week, the NRSC and the campaign of Arizona Republican Senate nominee Blake Masters placed their first coordinated campaign-ad spending of the cycle. On August 19, Fox News reported that the NRSC booked $2.2 million in advertising for Arizona and Wisconsin.

The most widespread insider critique of Scott’s stewardship of the NRSC centers on his consultants. Scott has long employed OnMessage, an established Republican consulting firm. Rival consultants argue that since Scott became NRSC chair, OnMessage has had a near monopoly over NRSC contracts. They argue that the NRSC never seriously offered request for proposals, or RFPs, from other firms and instead gave most of its contract work to the firm that has been a longtime vendor to Scott.

Hartline denied that the NRSC is excessively using any one vendor.

“No, OnMessage does not have a monopoly on contracts,” Hartline said in an email. “We have dozens of vendors. The ones complaining to you just weren’t good enough to get contracts.”

Sniping among political consultants over committee contracts is as common as among nerds at a science fiction convention. But of the near-dozen Republicans interviewed for this story, it was a common data point in arguing that Scott is focused on his team and his ambitions rather than the GOP’s as a whole.

“When OnMessage came in, they cut out a lot of other consultants,” the former top NRSC staffer said. “They always do that. That’s their M.O.”

OnMessage did not respond to request for comment by the time this piece was published.

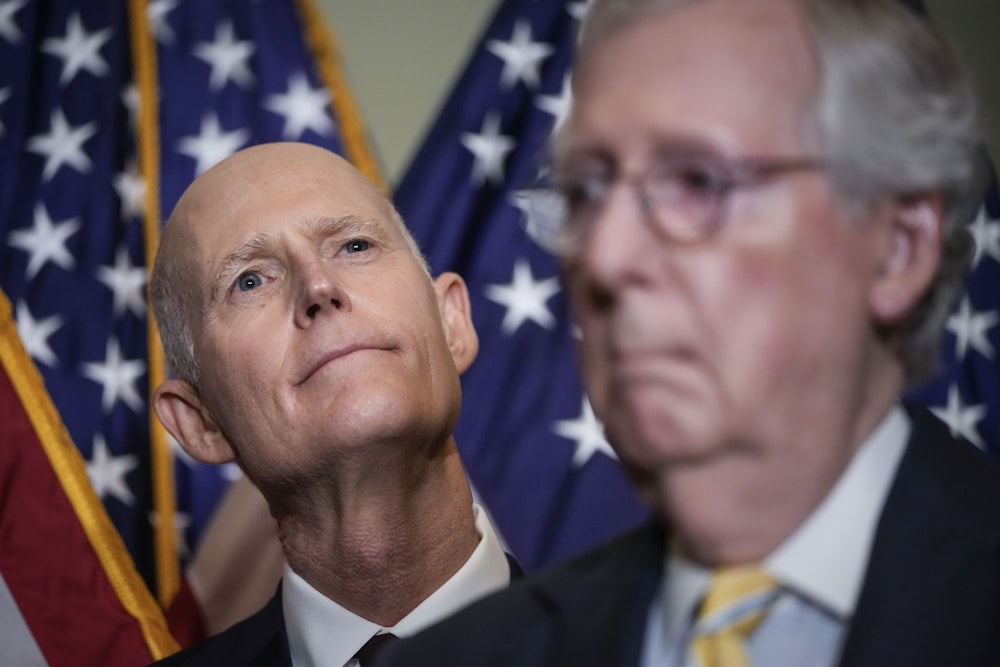

With only a few months to go before the midterm elections, Republicans now find themselves in a situation where Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell is tamping down expectations about Republicans’ chances in the midterm cycles. In August, McConnell said, “I think there’s probably a greater likelihood the House flips than the Senate.”

Some Republican operatives interviewed for this story say Scott is partially to blame for candidate recruitment. The NRSC and its chair are traditionally neutral in Republican primaries (like the analogous Democratic gubernatorial and congressional focused committees), so meddling in primaries or endorsement would be out of the question. But the argument goes that Scott could have spent more time directly recruiting competitive candidates and steering aspiring lawmakers to different offices to avoid bitterly divided primaries. But doing so might also antagonize or alienate Donald Trump and his supporters—something Scott is less interested in doing than, say, McConnell.

“He doesn’t want to upset the base by picking favorites in a primary, even though getting involved will lead to better candidates, as we saw in 2014,” a veteran Republican campaign operative said. “He doesn’t want to tick off the base.”

No Republican I talked to for this story thinks all is lost. They still expect the GOP will regain control of the Senate. But they fret that if it does, Republicans will have something like a 51-seat margin come January—not a more robust 53 or 54 seats.

A more focused chair might have been obsessed with growing the Senate majority as much as possible. But Scott’s moves suggest he’s focused on another influential political office. “We’re on knife’s edge in the Senate, and fundraising is going bad,” a veteran Republican strategist said. “We don’t know where the money went, necessarily, on a lot of this stuff. We don’t have good ads going out there. Candidates feel like they’ve been left in the dark, and Rick Scott seems to be running for president.”