After the FBI executed a search

warrant against Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago, the case against Trump would seem

like a slam dunk. The FBI found 11

sets of highly classified documents among the 20 boxes they removed,

reportedly including highly classified material on U.S. nuclear

technology and payrolls

for American spies overseas. Despite ludicrous claims that he had declassified

these documents with

his mind prior to leaving the White House, the consensus of national

security experts is that he had no

right to them even if they weren’t classified.

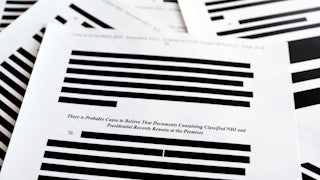

The warrant the FBI served indicated that Trump is being investigated for removal or destruction of records, obstruction of justice, and violating the Espionage Act. The last can include refusal to return national security documents upon request even if they aren’t classified. Thus, when the FBI showed up and confiscated top secret documents that the president had reportedly claimed (via his lawyers) that he didn’t have, it would seem like an open-and-shut case.

It is hard to find an innocent explanation for what Trump has done. But this is Donald Trump, who has managed to avoid consequences throughout a lifetime of cheating. There are myriad ways this can go sideways.

The first is the internal relationship between the FBI and the Department of Justice. We’ve already seen credible threats against FBI agents and members of the judiciary who implemented and executed the warrant. FBI Director Christopher Wray is a card-carrying member of the Federalist Society, appointed by Trump, leading a traditionally conservative organization riddled with Trump sympathizers. There is undoubtedly going to be strong internal pushback against an indictment by the Department of Justice.

There is also recognition by the FBI and DOJ that the indictment of a former president who is likely to run again is unprecedented. Not only this, but polarization and antipathy between the two political parties has reached a level unseen since before the Civil War. Indicting Trump is likely to set off violence. Worse, convicting him and sending him to prison could set off a chain of events that could expedite the dissolution of the United States, as internal pressure within red states mounts to formally cease the recognition of the authority and legitimacy of the federal government. Wray and Attorney General Merrick Garland are both keenly aware of this possibility, which may dissuade them from an indictment, arrest, and prosecution.

This isn’t the worst of it. The Supreme Court seems primed to look at Trump’s case from the most positive angle possible. There are several paths that the Trump legal team could take to defend their client, and the court would likely be favorably disposed toward all of them.

First, there’s the question of whether the crimes hinted at in the warrant took place while Trump was still president and if they were a part of his duties as president. As a rule, presidents are completely immune from civil action for things they did while in office (it’s called “absolute immunity”). More complicated is whether the president has qualified immunity from prosecution for crimes committed in office. It will come down to whether the court buys the idea that his actions were within the scope of his job—in this case, the act of handling classified documents and removing personal effects from the White House at the end of his term. This might seem like a stretch, but remember that conservative courts believe police officers are allowed to beat suspects to death (which is illegal) during an arrest, if it occurred as a part of their duties. Recent Supreme Court decisions have upheld broad qualified immunity for police officers, and at lower courts this reaches absurd levels. Police who kill completely innocent people (such as Philando Castille and John Crawford) rarely suffer any consequences worse than two weeks of paid vacation.

Then there is the matter of legal and historical tradition. Justice Samuel Alito made it clear that legal tradition is more important than the actual law in his Dobbs v. Jackson decision. Trump’s legal team can make a strong argument to Alito and others that there is a tradition of refusing to indict former presidents for their actions in office, even if these criminal actions fell outside the scope of their jobs. Gerald Ford’s pardon of Richard Nixon will factor heavily into this, as will the notion that this is an impartial application of the law. Trump’s legal team would argue that certainly Americans don’t want the next Republican administration to come back in 2025 and give Biden the death penalty for jaywalking or some other ridiculous charge, right?

While prosecutors are likely to point out that letting Trump go unpunished opens the door to dictatorship, the Supreme Court is also likely to accept the counter argument that the Constitution already provides a method to deal with wannabe dictators who break the law: impeachment. The Supreme Court would happily ignore the reality that in our hyperpolarized society you couldn’t get 67 votes to convict in the Senate regardless of what Trump did. He could literally murder someone on Fifth Avenue, or I guess these days South Ocean Boulevard, and the votes wouldn’t be there. The current Supreme Court is committed to justice in the abstract, and only in the abstract.

There are also questions about the constitutionality of the Espionage Act, which predates the modern classification system, and has elements that are broad and vague and that may infringe on the First Amendment. One could also make the argument that 18 U.S. Code § 2071 (concealment, removal, or mutilation of government documents) violates Trump’s constitutional rights because it bars people from holding office if convicted, but the Constitution already sets forth the requirements for the office of President. And obstruction of justice can be difficult to prove because it requires proving intent.

The upshot is that the road ahead for Trump isn’t as bad as it looks upon cursory examination. There are innumerable ways that Trump’s legal team can go at this. At the same time, the FBI and DOJ are going to be reluctant to pursue charges that they’re not 100 percent certain they can get a conviction on—or in the case of obstruction of justice, may not be worth the tap on the wrist that is the likely outcome. If they try and fail, it likely sets off violence and undermines the perceived credibility of their agencies. If they try, and succeed, it could spark a new nullification crisis on the right. Or, in the worst outcome imaginable, they could not try Trump at all, and thus pave the way for despots who would also turn over state secrets to hostile foreign powers for profit, as Trump may have done already. This entire fiasco is a Kobayashi Maru nightmare no-win scenario for the U.S. as a democracy and a win for the GOP as it eyes how it can secure permanent single-party rule past 2024.