“We’ve sort of become a nation of whiners. You just hear this constant whining, complaining about a loss of competitiveness, America in decline.… You’ve heard of mental depression; this is a mental recession.”

—UBS vice chairman Phil Gramm in July 2008, seven months into the worst recession since the Great Depression and nine days before Gramm withdrew as co-chairman of fellow Republican John McCain’s presidential campaign

“Income inequality is not rising.”

—U.S. Policy Metrics senior adviser Phil Gramm, along with co-authors Robert Ekelund, professor of economics emeritus at Auburn University, and John Early, former assistant commissioner for the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in The Myth of American Inequality: How Government Biases Policy Debate, published September 15

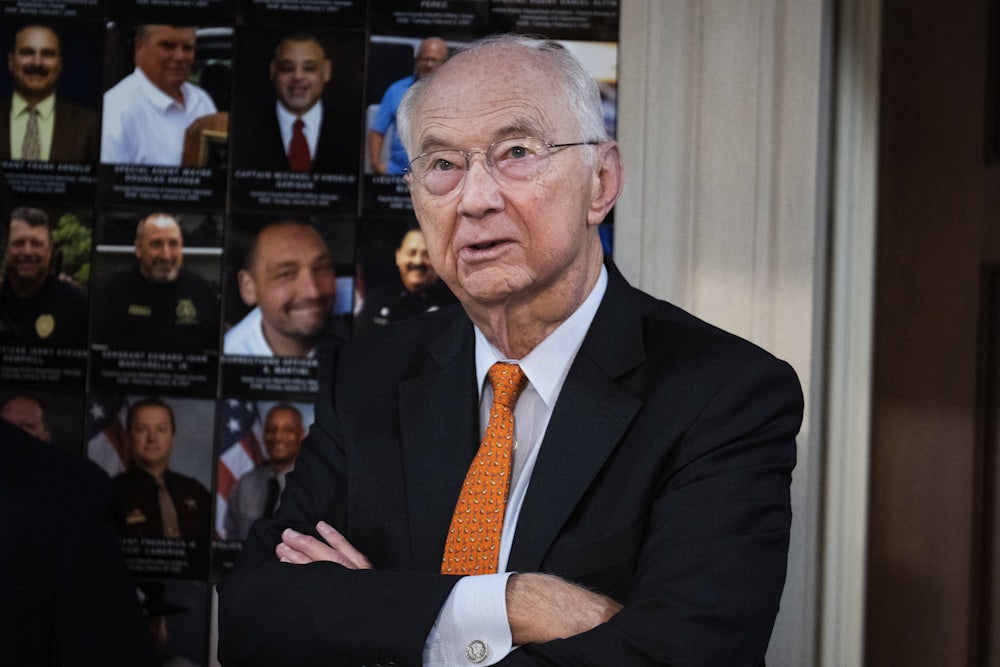

I’ve always had a soft spot for Phil Gramm. The former senator and onetime economist at Texas A&M amassed a fearsome campaign war chest to run for the Republican presidential nomination in 1995, only to quit the race in February 1996 after suffering humiliating defeats in Iowa and New Hampshire. That year’s Republican nominee, Bob Dole, would later lose to President Bill Clinton. Twelve years later, Gramm inadvertently helped Democrat Barack Obama defeat Republican John McCain for president by pooh-poohing the Great Recession.

Gramm is a plainspoken man who would rather piss you off than get your vote. He can’t help himself! But unlike the truth-tellers whom history will remember as Profiles in Courage, Gramm, if he’s remembered at all, will be memorialized as a blunt talker who was always wrong—exuberantly, audaciously wrong, in a Byronic sort of way, but wrong nonetheless.

Gramm’s latest exercise in error is The Myth of American Inequality. Gramm and his co-authors, Robert Ekelund and John Early, maintain that America is becoming not more economically unequal but less so. This is a very daring argument, given the mountain of evidence to the contrary. Other conservatives have argued that growing economic inequality doesn’t matter, but not many have argued that economic inequality doesn’t exist. How do you even make such an argument? Here’s how, in four easy steps.

Scramble the timeline. “Income inequality is not rising,” Gramm and his co-authors state. “It has in fact fallen by 3.0 percent since 1947 as compared to the 22.9 percent increase shown in the Census measure.” This is sheer lunacy.

As Gramm well knows, incomes became more equal from the 1930s through the late 1970s. Around 1979, that trend reversed itself and incomes started becoming less equal. They have become steadily less equal ever since, and today, according to Berkeley economist Emmanuel Saez, the top 10 percent’s share of national income exceeds the previous high in 1929 (scroll down to Figure One).

If you start your timeline in 1947, as Gramm and Co. do, you capture a huge chunk of the pre-1979 decline. If you see someone mapping the inequality trend who doesn’t begin around 1979, that’s an immediate tipoff that they’re pulling a fast one.

For the record, though, income inequality by any honest measure has increased almost as much since 1947 as it has since 1979.

Emphasize broad-based inequality. As I explained in my 2012 book, The Great Divergence, there is not one income-inequality trend but two coinciding trends. The starker trend, mapped by Saez and Thomas Piketty, shows huge gains in the pre-tax share of national income by the top 10 percent, the top 1 percent, and the top 0.1 percent, with the gains getting larger the higher you go. (You can make these gains slightly smaller by factoring in taxes and government transfers, but only slightly.) The second, less stark trend is the broad-based post-1979 growth in income inequality as measured by the Gini index and/or by dividing the population into five “quintiles”: the bottom 20 percent, second 20 percent, middle 20 percent, and so on. The gap here, which has mostly stabilized over the past couple of decades, is between college graduates and non–college graduates. Among the reasons you haven’t lately seen the broad-based trend worsening is a weakening in the economic strength of the professional-managerial class (nicely described in 2013 by the late Barbara Ehrenreich and her former husband, the psychologist and author John Ehrenreich).

Gramm and Co. build their book around the Census Bureau’s annual inequality reports, which mostly map broad-based inequality. The latest Census report, which came out last week, showed that 2021 saw the first increase in the Gini index since 2011. But (as the report notes) that’s probably because low-wage workers who dropped out of the workforce at the height of the Covid pandemic in 2020 returned to full-time work in large numbers in 2021 (as documented in monthly jobs reports by the Bureau of Labor Statistics).

Pretend the inequality trend is a poverty story. If you remember nothing else, remember this: The post-1979 income inequality trend is a story about middle-class decline. Average wage growth slowed dramatically in absolute terms after 1979, and the gap between the middle class and the rich became a chasm.

In their book, Gramm and company talk a lot about poverty. That’s a distraction from the inequality story, because while life has been getting steadily worse for the middle class, it’s been getting somewhat better for the poor. The reason life has gotten somewhat better for the poor is that the government has gotten more generous in extending benefits to the poor. The nonprofit Center on Budget and Policy Priorities reported in 2019 that the poverty rate had fallen by nearly half since 1967, thanks mostly to income security programs. More recently, The New York Times’ Jason DeParle reported that child poverty has fallen 59 percent since 1993, in large part because of expansions in the Earned Income Tax Credit. We still have far to go, but today we are a less desperately poor society than we were in 1979. This is a humanitarian triumph.

Gramm doesn’t see it that way.

In January 1995, Gramm said on Meet the Press: “We have gone too far in creating an entitlement society.… If we stay on the same road we’ve been traveling, in 20 years we’re not going to be living in the same country we grew up in.”

Now it’s 27 years later and Gramm and his co-authors aren’t happy:

It is hard to see how a middle-income family with two adults both working would not resent the fact that other prime work-age people who are not working at all are just about as well off as they are.… It seems unjust that 60 percent of Americans have virtually the same standard of living despite dramatic differences in their work effort and levels of earned income.

The convergence Gramm describes is real, if exaggerated here, and it helps explain the bitterness of our politics today. As life gets no better for the middle class and government programs make life somewhat better for the poor, the difference between being middle class and being poor becomes … blurry. I don’t doubt that this creates middle-class resentment. But it’s perverse for Gramm to want to resolve this by making the poor poorer. If work is not being rewarded sufficiently in the private sector—and it isn’t—Gramm should favor resolving that by securing workers a living wage (by, for instance, increasing the $7.25 hourly minimum wage and removing government obstacles to unionization).

Reclassify health insurance as welfare. Gramm bellyaches in his new book that the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, when it compares levels of income inequality in different nations, doesn’t figure in health insurance, on the grounds that it doesn’t consider health care to be income. Most OECD countries have national health insurance that essentially removes health care from the wage economy. Gramm thinks that’s a scandal.

Gramm takes census data on pretax income and adds in the value of taxes, employee benefits, and government assistance. Fair enough. But if you want to argue that income inequality is a fantasy, that adjustment won’t get you there; you’ll just get a slightly less pronounced inequality trend. If you want to say black is white and up is down, you have to factor in the value of the benefit that OECD excludes: health insurance, funded privately or publicly.

Here’s how Berkeley economist Gabriel Zucman, who hasn’t read Gramm’s book but did read an August Wall Street Journal op-ed summarizing its main points, explained the health insurance problem in an email:

The claim on the high growth of bottom incomes is largely due to the inclusion of Medicaid and other in-kind health transfers at cost. Because health care is so incredibly expensive in the US this looks like a huge transfer to the bottom but of course that’s not income flowing to Medicaid beneficiaries, but to the providers of health care services, many of whom are towards the top of the distribution.

I suppose Gramm would answer that access to health care has market value and therefore must be income. But it isn’t the sort of market value that any of us is eager to realize, because that would entail getting sick. By Gramm’s logic, the sicker you get, the richer you become.

There’s more to say about Gramm’s book. In the next installment—yes, I will write about this twice!—I’ll discuss how Gramm addresses the seemingly insurmountable fact that the rich have gotten much, much richer. He answers, in part, by asserting that Ebenezer Scrooge is actually a very admirable character who’s been widely misunderstood. I kid you not.