In 2018, when Washington, D.C., was having a high-profile argument over Initiative 77, a ballot measure to end the lower tipped minimum wage in the city, Max Hawla was making a decent income as a bartender and barback. With his tips he pulled in about $40,000 a year, even though the minimum wage he was guaranteed by city law was just $3.33 an hour. To make that income, though, he had to work five bar shifts a week—which are physically demanding and usually run much longer than eight consecutive hours.

He loved getting paid in tips because he felt like it rewarded him for working as hard as he wanted. And he feared that if Initiative 77 succeeded—which would have raised the tipped wage over the course of eight years to match the city’s regular minimum wage, currently $16.10 an hour—those tips would dry up. “I was staunchly against Initiative 77,” he said. He remembers changing his profile picture to a crossed-out 77. He wasn’t alone. Although the initiative passed that June by a clear 12-point margin, a group funded by the National Restaurant Association calling itself Save Our Tips rounded up bartenders and servers like Hawla and flooded the city council with calls to overturn it. Lawmakers heeded the call and reversed the ballot measure just four months after voters approved it and before it could go into effect.

But Hawla has since done a 180 on the issue. In September 2021, he took a trip to Seattle, where Washington state law has done away with the lower tipped wage and requires all employees to be paid the same minimum as any other worker. Hawla visited a friend at his bartending job and asked him how he liked working without a tip credit. “He was like, ‘What’s a tip credit?’” Hawla recalled. Hawla explained that his own base wage was only $5 an hour (Washington D.C.’s tipped minimum had risen ever so slightly since the 2018 initiative) and that his tips were required to make up the difference between that and Washington, D.C.’s $15.20 minimum wage at the time. “He was like, ‘That’s stupid,’” Hawla recalled. His friend told him he was making $15 an hour and getting just as much in tips. “It was so simple,” Hawla said. “I was like, ‘OK, I’ve been lied to.’”

A month after he returned to Washington, D.C., he saw a sign urging people to vote yes on Initiative 82 on his way to work. He looked it up, finding out that it was a measure on this November’s ballot to once again get rid of the tipped wage and require tipped workers be paid at least $16.10 an hour by 2027. Hawla is now a staunch supporter, working with the campaign to get it passed.

He is part of a sea change that advocates are eager to take advantage of. After the pandemic, employees and employers alike in the restaurant industry have come to see the tipped wage as untenable. Laid-off restaurant workers filed for unemployment insurance, only to find out their wages were too low to qualify if their tips weren’t reported by their employers. When they went back to work, tips were depressed and unpredictable as people still stayed home.

In a March survey conducted by One Fair Wage, a national coalition that advocates to end subminimum wages, only 41 percent of restaurant workers said their tips were enough to ensure they were earning the full minimum wage where they lived. Now, in the tight labor market, many restaurants have had to voluntarily raise their base wages to attract and retain employees. One Fair Wage has tracked nearly 4,500 tipped businesses that are paying above their state’s tipped minimum wage, most of them at the regular minimum wage or higher. “It’s like night and day,” said Saru Jayaraman, president of One Fair Wage. “It really is this very historic moment.”

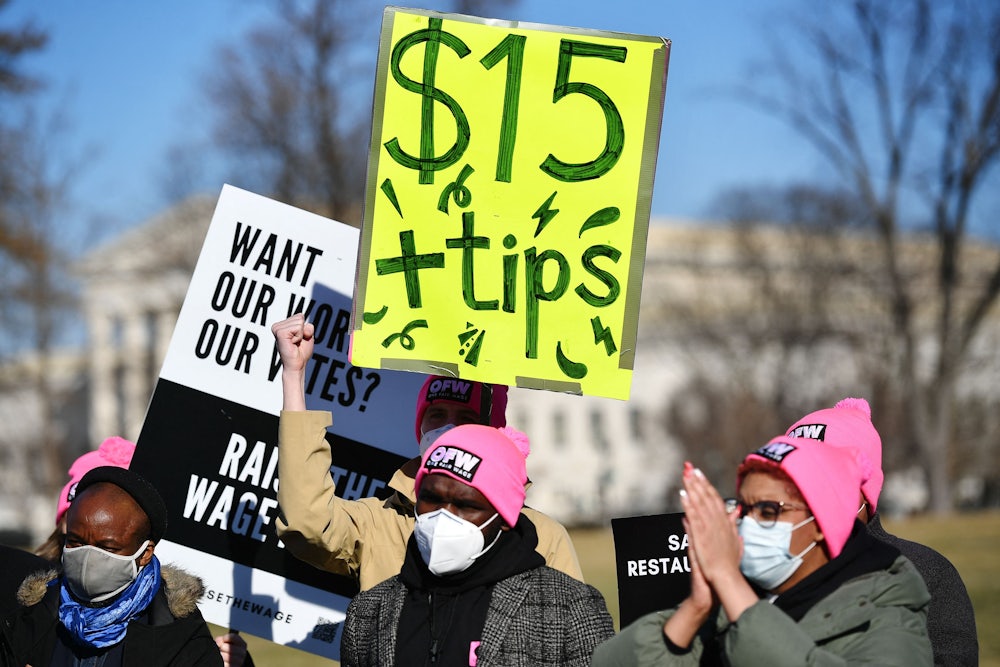

Advocates for getting rid of the tipped wage have launched into action. Years before the pandemic, they won three different ballot measures to end the tipped wage in Maine, Michigan, and Washington, D.C., only to watch as lawmakers in each place turned around and undid the measures. Now they’re waging new ballot campaigns this fall to get the job done and end the tipped wage once and for all. They also have campaigns to end it in 25 states, either through legislation or ballot measures, including proposed bills in New York, Illinois, Massachusetts, and Puerto Rico for next year’s legislative sessions and a ballot campaign in Ohio in 2024.

“What this new moment allows us to do is to win,” Jayaraman said. “It’s really our year of redemption.”

The tipped minimum wage dates back to the post-emancipation years, when employers refused to pay formerly enslaved Black workers in restaurants and railcars a full wage. Instead, they forced them to live off of the kindness of customers and their tips. That practice was enshrined in federal labor law in 1966 when the federal minimum wage was expanded to cover tipped restaurant and hotel workers but allowed employers to pay those workers at a lower rate as long as their tips made up the difference.

That’s how federal law still works today: A worker who receives tips, including not just restaurant workers but nail salon technicians, hairdressers, car wash workers, and people in plenty of other fields that get tipped, can be paid as little as $2.13 an hour, although the law states that their tips must make up the difference between the full minimum wage of $7.25 an hour. An employer is required to step in if tips don’t fill in the gap, but in practice many employers don’t. Between 2010 and 2012 the Department of Labor found 1,170 tip credit violations.

Some states have left this practice behind entirely. Starting in 1975, eight states—Alaska, California, Hawaii, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington—abolished their tipped minimum wages and required the same pay floor for all workers. But it has often been an uphill battle to add more states to that list.

In 2018, just before Michigan voters were set to weigh in on a ballot measure to raise the minimum wage and get rid of the tipped wage, as well as guarantee workers paid sick leave, the legislature passed its own similar legislation to remove it from the ballot and give itself the ability to later water it down. It fulfilled that promise in that year’s lame duck session, getting rid of the provision that would have eliminated the tipped minimum wage.

Advocates there have already tasted their own sweet revenge, however. The legislature’s move, a judge ruled this July, was unconstitutional. The ruling won’t be enforced until February, but when it is tipped workers will have to be paid $12 an hour, with tips on top of that.

Advocates aren’t stopping there. They’ve already collected 610,000 signatures to put a measure on the 2024 ballot to increase the wage to $15 for everyone, not just for tipped workers but also youths and those with disabilities. “We want to make sure that all workers are making a living wage regardless of the industry in which they are a part of,” said Roland Leggett, campaign manager for the Michigan effort. “We don’t want any workers to be left behind.” Right now, the campaign is recruiting and training over 30,000 tipped and low-wage workers—not just servers, but Uber drivers and barbers and all kinds of tipped workers—to have conversations with voters about the ballot measure.

With Democratic Governor Gretchen Whitmer supporting the idea, Jayaraman trusts that she would veto any attempt to roll this one back if it passes. Leggett is also confident. “What it’s going to say when we win,” he said, “is that, despite the fact that we had an adversarial legislature for many years that was unwilling to listen to the will of the people, that we were able to prevail.”

Advocates in Portland, Maine, are also hoping to prove that the will of the people prevails in the end. Mike Sylvester first ran for office as state representative in 2016, when a referendum was also on the ballot to increase the state minimum wage to $12 and get rid of the lower wage for tipped workers. It easily passed. But when he entered the state legislature early that next year, he watched as a deluge of about 20 bills were introduced to roll back different aspects of it. Progressive lawmakers were able to hold on to much of the changes, including increasing the minimum wage to $12 by 2020, but lawmakers reinstated the tipped minimum wage.

Instead of instituting change across the full state, advocates in Maine have shifted their attention to the local level. They’re pushing a ballot measure to raise the minimum wage to $18 an hour in Portland—the state’s largest city—that would apply to all workers. “Portland is the foodie city of the state, so it seemed like the logical place to start and hope that the rest of the state will follow,” Sylvester said. He and One Fair Wage have teamed up with the local Democratic Socialists of America chapter, which was also working on a ballot campaign to raise the minimum wage. “It’ll be historic, the first measure that ever has passed to increase the minimum wage and include every worker,” Sylvester said. Unlike at the state level, the Portland city council has to wait five years to overturn such a measure if it passes. If it succeeds, they might take it to other cities next such as Bangor or Lewiston, or perhaps run another statewide one.

Opposition is starting to form, and the tactic it’s taken is against ballot measures in general, arguing that it’s better for policy to be made through legislation instead. “They’re trying this new tactic because they’ve tried defeating multiple referendums one by one and that hasn’t worked,” Sylvester said. But it’s a far cry from Save Our Tips, which was formed in Maine to defeat the 2016 measure and was staunchly focused on its opposition to ending the tipped wage.

The opposition is also starting to appear in Washington, D.C., although it’s only just gearing up—it was quiet while advocates collected signatures, although it filed numerous legal challenges over whether the measure could appear on the ballot, all of which the pro campaign has won. The National Restaurant Association has historically fought these efforts tooth and nail—it dumped over $95,000 into the Save Our Tips campaign that was exported from Maine to Washington, D.C., against Initiative 77 in 2018. But “they have been more mute in the last six to nine months than we’ve ever seen them,” Jayaraman said. “There’s been no public war in the same way.” Instead of calling itself Save Our Tips, this time the anti-minimum wage effort rebranded and is called simply Vote No on 82.

Meanwhile, Chairman of the D.C. Council Phil Mendelson, who voted to overturn Initiative 77, has publicly pledged to respect the will of the voters if the new measure passes. Most other councilmembers have pledged not to overturn it, Jayaraman said. Many others who originally voted to undo it lost their seats in the aftermath, and more progressive members have been elected in their place.

A lot of voters are still “livid” about the council overriding their votes in 2018, said Ryan O’Leary, who proposed Initiative 82. “The general population has had a consensus shift around work and what a worker deserves,” he said. He’s also been going into restaurants at slow times of the day to talk to workers. “Almost every waiter and food runner and busser I talked to was excited to learn about this,” he said. A poll commissioned by One Fair Wage and conducted by Lake Research Partners found 91 percent support among Washington, D.C., restaurant workers.

No on 82 has amassed a war chest, taking in $91,000 between July and September, including a $4,200 donation from the National Restaurant Association, which also donated money earlier to fund the legal campaign, and $10,000 from celebrity chef José Andrés’s ThinkFoodGroup. The group has $52,000 on hand, compared to $5,400 for O’Leary’s efforts. But O’Leary is confident that, with those kinds of polling numbers, some support could wane and the measure could still easily make it over the finish line.

Hawla’s looking forward to what it’ll mean for him personally if it passes. “It’ll put more money in my pocket,” he said. He’s gotten used to not knowing what his income is going to be week to week and month to month from doing this work for seven years, but when he describes that to people with office jobs they’re baffled. Ending the tipped wage “is a baseline of security,” he said.

He’s been talking to friends and coworkers about the measure, and when he puts it in simple terms—that it’ll raise their pay and there’s no evidence their tips will decrease—they tend to support it. “There’s definitely been a reconsidering, and it’s part of the broader social and political reckoning we’ve been having since March 2020,” Hawla said. “People are just really burned out from having to work for shit wages.”