It sounds like a vintage Abbott and Costello sketch, but the question of “who’s on first” continues to roil the Democrats. Later this week, a key committee of the Democratic National Committee is expected to decide the initial order of the 2024 presidential primaries. At the moment, though, the members of the DNC’s Rules and Bylaws Committee are mired in limbo waiting for recommendations from the White House.

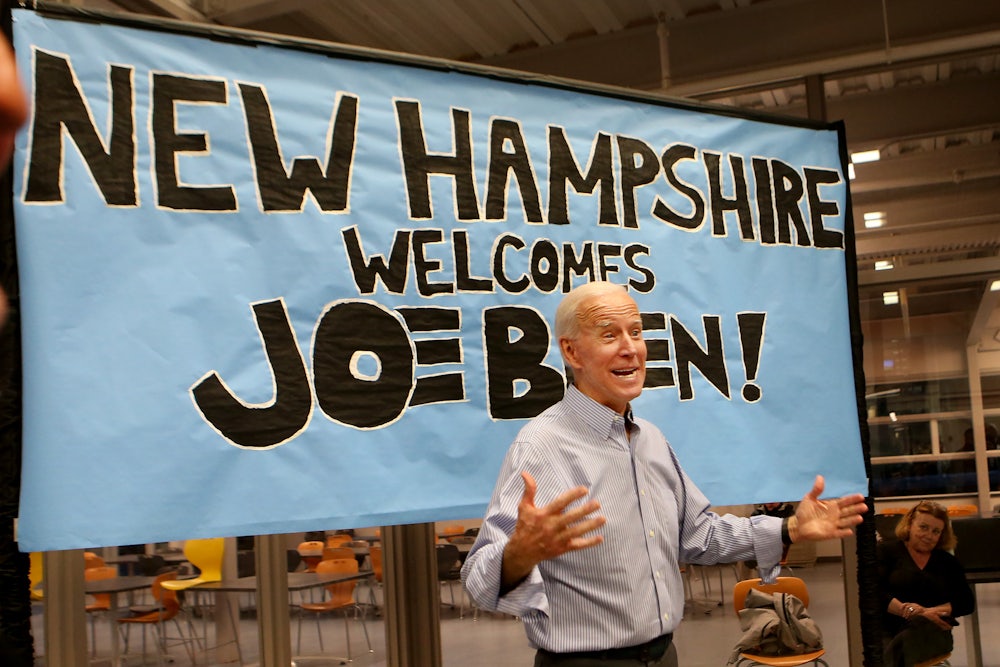

Maybe the Democrats wouldn’t have come to this point of uncertainty if the definite results from the opening-gun 2020 Iowa caucuses hadn’t been delayed for more than three weeks. Maybe the traditional front-of-the-pack status of the New Hampshire primary would have been ratified by now if Joe Biden had not finished fifth in the state with just 8 percent of the vote in 2020. But in truth, the Democrats have long chafed at the tradition of beginning the nomination fight in Iowa and New Hampshire—two states with all the diversity of an Icelandic phone directory. As a result, the DNC required a formal application from every state that wanted its primary to be among the first four or five on the calendar.

As of midafternoon on Tuesday, members of the DNC’s rules committee had not even received an agenda for Thursday’s meeting. What may be complicating everything is the status of Biden’s 2024 ambitions as the nation’s first four-score-year-old president. If Biden, as he has broadly hinted, runs for a second term, the major goal of the White House in setting the primary calendar would be to discourage the possibility of any serious opposition. But if Biden decides to go out on top after the relative success of the midterms, then the order of the 2024 primaries will partially shape the choice of his successor as the nominee.

With the almost certain demise of the Iowa caucuses, though, the Democrats’ current primary calendar actually needs minimal tinkering. Keeping New Hampshire as the first primary and simply adding a different Midwestern state later in the cycle would bequeath the Democrats a 2024 schedule that is diverse and representative of key constituencies, and gives outsider candidates (on the model of Jimmy Carter in 1976 and Pete Buttigieg in 2020) a chance to prove their mettle through personal campaigning rather than just expensive TV ads.

For all the griping about its monochromatic population, New Hampshire still offers a strong case as the kickoff state. The snows of New Hampshire have been the setting for long-shot candidates to break through and sometimes change history. The anti-war battalions that powered Eugene McCarthy’s challenge to Lyndon Johnson in 1968 helped convince LBJ not to seek another term. New Hampshire gave a scandal-scarred Bill Clinton a second chance in 1992 after he promised voters he’d be there for them “till the last dog dies.” But beyond tradition, New Hampshire embodies a key element of the modern Democratic Party—independent, college-educated, socially liberal voters. The state is geographically compact (no candidate will ever need to charter a plane in New Hampshire), comparatively affordable (the Boston media market is smaller than that of New York or Philadelphia), and can count votes quickly in its high-turnout primary.

The rest of the early calendar can more than compensate for New Hampshire’s disproportionately white electorate. Nevada, a swing state whose voting-age population is nearly 30 percent Latino, has been vying to jump to the front of the line. But dominated by the casino industry and its powerful union, the Culinary Workers, Nevada is atypical in too many ways to go first. Also, there is a strong practical argument against starting the primary season in the Pacific Time Zone, which would mean that the triumphant candidate would be giving a victory speech at a time when much of America had gone to bed.

Biden is president largely because he swept the 2020 South Carolina primary with its majority Black electorate. With Jaime Harrison, who lost a 2020 Senate race in the state, as the current DNC chair it is safe to assume that South Carolina can get anything it wants from the Democrats. Its reward would be to stay in the third slot in the primary calendar as the state that may well anoint the nominee rather than merely winnow the field.

What is missing is a Midwestern state to replace Iowa, which now has an all-Republican congressional delegation. For nearly two decades, Michigan has been vying to jump the queue, actually losing half of its delegates in 2008 as punishment from the DNC for holding an outlaw early primary. Awarding Michigan the last early slot (over its top rival, Minnesota) violates the long-standing principle that small states should go first, since Michigan is the tenth-most-populous state in the nation, more than three times the size of Iowa. But moving Michigan to the very front of the line would be even worse, since it would destroy the last vestiges of personal campaigning that allow a candidate who begins without a vast TV budget to woo voters in local coffee shops and VFW halls. That said, Michigan’s rebirth as a state with a Democratic edge under Governor Gretchen Whitmer probably will be enough to vault it onto the 2024 early calendar. But at least if Michigan is placed in the fourth slot on the calendar, the candidates, who have survived that long, would have by then raised enough to wage a credible campaign in a major state.

The hard thing for the DNC to accept and ordinary voters to understand is that there is no perfect calendar, no ideal order of the states. If the Democrats truly craved demographic perfection, they should erect a theme park in the Washington suburbs called “Campaign Land.” Pollsters could populate Campaign Land with a random sample of Democratic voters as the candidates move from a stage set with hay bales to a mock-up of an abandoned factory to a prototype of a new research laboratory supposedly constructed with federal funds under the Biden administration.

Short of going the theme-park route, a primary calendar that begins with New Hampshire, Nevada, South Carolina, and Michigan is about as good as the Democrats can pull off. It highlights three Democratic-leaning swing states plus South Carolina, the state whose primary anointed both Barack Obama and Biden. The danger for the Democrats—and this is so in character—is that they may overthink things in arranging a calendar for 2024 and beyond. Sometimes the best answers are the simplest.