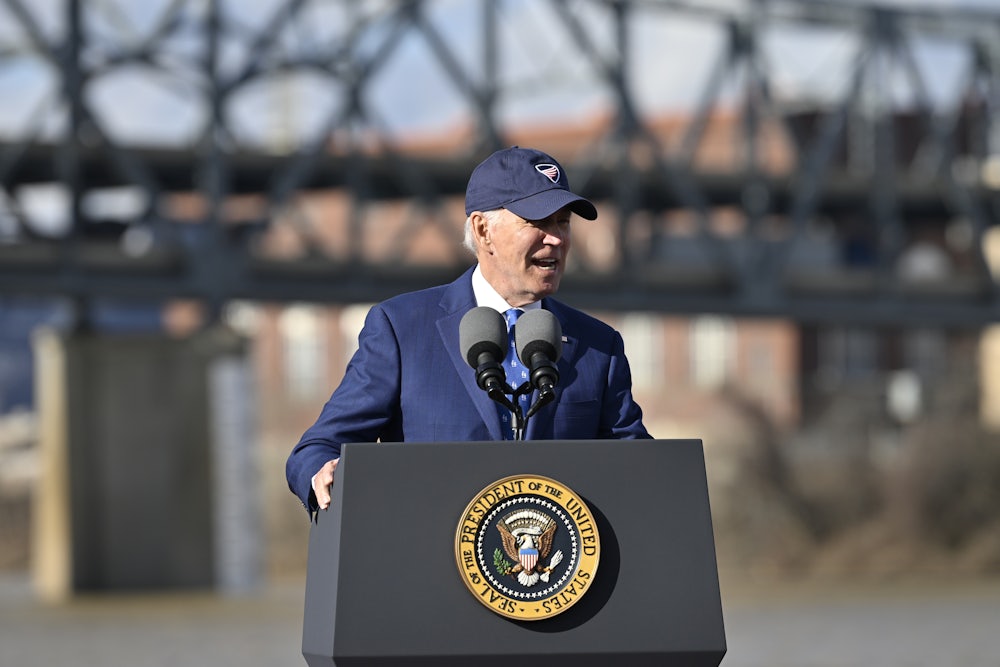

What now for Bidenomics? After two surprisingly, perhaps even shockingly, fruitful governing years for Democrats, the GOP—barely—holds the House. We’ve already seen the governing chaos caused by right-wing revolts against Republican leadership, and once the Kevin McCarthy saga is settled, we’ll likely see threats of investigations and impeachments. But don’t expect any substantive legislative progress.

This might be a very eventful policy year nonetheless. All eyes are now on the executive branch. The big question will be: Can the White House and the federal agencies make all of their legislative successes—the Inflation Reduction Act, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, and the CHIPS and Science Act—really work for the American people?

No doubt, these policies are a real break from the failures of neoliberalism. They invest public funds, from proper taxation on the wealthy and corporations who are otherwise skirting the law, in important new sectors of our future economy, from clean energy to semiconductor supply chains. They strengthen basic public scientific research. They strengthen government itself, from the IRS to the Department of Energy and more.

But whether these policies will actually work is an open question. In the year ahead, policymakers will face four important “choice points.” Their decisions will make the difference between a one-off set of government grants and tax credits and the ushering in of a new political order—a true split from market-only answers, and an embrace of sustained public investment in public goods that Americans will see, understand, and maybe even reward.

The four critical political economy questions for 2023: Will we plan? Will we repair? Will we embrace and amplify the role of government? And, as we seek to build roads and bridges, wind farms, and electric vehicle charging stations and semiconductor fabrication plans, will we listen to the communities who will be most affected by all of this change?

Will we embrace government planning?

For decades, open embrace of industrial policy was verboten. The idea that it is necessary, appropriate, and even good for the state to play a central role in deciding which industries rise and fall, how they are structured, and how they produce the goods and services we need: This was the policy that “shall not be named.” Sure, the Defense Department quietly nurtured the military-industrial complex, and various agencies enforced risk or competition regulations that made life easier or harder for industries. But they acted typically not with an explicit policy goal of onshoring or offshoring those industries, winding them up or winding them down, and almost never with job creation, worker power, and public safety in mind.

Covid-19, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and a political reckoning in the United States with what is required to address climate change changed all of that. Whether personal protective equipment, vaccines, or energy are produced at home or abroad, in friendly jurisdictions or hostile ones, these questions are no longer mostly about just-in-time logistics. They are now, more clearly than ever before, questions of life and death.

Which leads to choice point number one: Does Biden let each agency that got enormous pots of money and new authorities in the last legislative session burrow into their own siloes, responsive only to their congressional overseers? Or does the president insist that all these new laws add up to more than the sum of their parts? For all of this legislation to add up strategically, as National Economic Council Director Brian Deese often insists it must, the White House will have to drive alignment across agencies and communicate clear economic and sectoral priorities.

While the notion of “industrial planning” sometimes evokes more authoritarian political systems like China, the reality is that Western economies, U.S. states and localities, and well-run private sector firms all plan. Decades of research tell us that industrial strategies are more likely to be effective if they are part of an economy-wide plan, and more likely to be legitimate if this plan is inclusive, democratically decided, and accountable. What must be produced to meet the needs of a country as vast as ours? Where must it be produced to bring more of the productive capacity of our country to bear? Who should produce, and who should benefit? These questions must drive a strategic industrial plan that meets the unique challenges of the U.S. economy over the next decade.

Will we repair past harms?

The neoliberal era was premised on the assumption that markets would allocate capital efficiently—and, in certain ways, they did. Corporations moved manufacturing facilities where costs were low, often offshore. But they did so without regard to the kinds of things only democratically accountable governments attend to: whether the geographic distribution of economic opportunity contributes to a strong, vibrant democracy, and whether the location of new manufacturing facilities would strengthen or undermine our towns, cities, and communities. There’s a reason the narrative that Nafta cost American jobs has haunted Democrats for decades.

Setting a new economic North Star is about more than producing resilient supply chains or making efficient use of nearby colleges and training centers for workforce development, however important both of those might be. It is also about repairing past harm—some of which far predates the neoliberal era, all of which was made worse by neoliberalism’s “let the market decide” dogma.

In the coming years, government will write new rules and make important choices, shifting capital and structuring markets for decades to come. Where will our new manufacturing centers be located? What features, from the treatment of workers to the use of natural resources, will distinguish our most innovative, productive firms? Values beyond economic efficiency will guide those choices, and a new North Star must make those plain.

One value should be to recognize and repair the harm of years of neoliberal disinvestment and extraction, both public and private. This will not be easy. The Biden administration has already pledged a “whole-of-government” approach to race equity that directs 40 percent of the benefits of investments to “disadvantaged communities that are marginalized, underserved, and overburdened by pollution.”

This is certainly a reparative move, in that it requires acknowledging past harm. Fixing past harm was, for example, the basis of the administration’s summer 2022 decision to cancel hundreds of billions of dollars in student debt. Certainly, part of the argument for debt cancellation is about borrowers’ future economic contributions, but part of the policy decision was based on Occupy Wall Street–era arguments that our current level of student debt is unfair and extractive, because borrowers who took out loans never got the degrees or employment benefits promised. Whether the Biden administration has the political backbone to design IRA, supply chain, and infrastructure policies such that they redress past harms and prevent future concentrations of economic and political power remains an open question as we head into 2023. It is a critical one.

Will we make government visible?

The role and reputation of government itself is also important as we begin implementation at scale. The Biden team must strengthen government’s public legitimacy by driving a visible government plan that can shift public views toward government.

This will be a very tall order. Polling consistently shows that across the country, Americans of all ages and demographic backgrounds lack trust in the federal government, although Democratic and independent voters have more faith in government than do Republicans. Making government actions visible—marketing them, advertising them, taking full credit—might be risky given anti-government sentiment and the polarization of government itself, but this is a risk worth taking given how essential belief in government action is to our democracy.

This will be most important for the Treasury Department. For the past decade, we’ve had policy-by-tax code, from subsidies for health insurance to Covid recovery funds. This is largely the result of Senate rules that make more sensible policymaking impossible. It is indirect, and largely invisible. As Suzanne Mettler describes, this submerges the state. Voters don’t see what is happening and can’t hold the government to account, or reward it, for outcomes.

Correcting for these flaws is ultimately the job of Congress, but there are steps Treasury officials can take to add accountability, guidance, and oversight to guide these dollars in ways that align with industrial policy aims. Today’s Treasury leadership has done an admirable job of explaining itself. But government and those of us who are pro-government allies must do much, much more so that the American people understand government’s role in structuring and driving all manner of public benefits.

The new economics is such an important break from the past. Getting the public to see that this is the work of government—not just a policy here or there, but an entirely new governmental approach—critical to not just the success of these laws, but to our basic democratic project.

Who will we listen to, elite experts or ordinary citizens?

Most people still think about neoliberalism as a pro-market, libertarian-esque economic project. But the deepest part of the neoliberal legacy is not economic per se; it is about governance. The neoliberal fight is less about left versus right, and more about who gets listened to and whose advice gets baked into policy design: the expert economist or the union member, the corporate lawyer or the movement leader.

This leads to our final choice point for the coming year: As implementation decisions proceed, and our country builds out its manufacturing capacity at a blistering pace, whose expertise will the Biden administration make central? Trained experts of course matter on everything from economic to environmental effects. But so does the knowledge of line workers, nurses and orderlies, and everyday citizens. Will this administration, as it implements its $4 trillion agenda, find a smart and effective way to include the expertise of people whose lives will be most affected by the siting of the new wind farm or the implementation of health insurance directives?

Many prominent thinkers are understandably worried that such local expertise—a.k.a. democracy—will hobble our ability to build good things quickly, and with it all of the good intentions of 2022’s hard-fought legislative wins. Whether the Biden team, and local and state governments around the country, devise more robust ways to get input from the people who are least often heard from may determine whether any of the 2022 legislation leaves a legacy that lasts far beyond the next few years, and whether it’s a legacy our children will be proud of.

Conclusion

The battle for our new economy has only just begun. Republican lawmakers are already trying to claw back critical funding. Corporate interests are lining up to take advantage of all that the new laws have to offer. The question now is whether progressives and those fighting for the public interest—less informed than businesses, and less organized, but far more important for our politics—will step effectively onto the playing field. Even with no legislative prospects in sight for the next two years, 2023 will be a critical year in our fight for the economy the American people deserve.