Central to Joe Biden’s political persona as Middle-Class Joe—the heir to the liberal populism of Harry Truman—is the president’s pedestrian educational record. Unlike every Democratic presidential nominee from Michael Dukakis in 1988 (Harvard) to Hillary Clinton in 2016 (Yale Law School), Biden never attended school anywhere with a whiff of the Ivy League.

As Richard Ben Cramer described it in What It Takes, his intimate portrait of the president at the time of his initial 1987 bid for the White House, Biden had modest educational ambitions as an early 1960s undergraduate at the University of Delaware. “A gentleman’s C seemed good enough,” Cramer writes. “It wasn’t that Joe lacked brains or ambition.... It’s just he didn’t give a damn. He didn’t want Harvard Medical School. Law school, probably, but it didn’t matter which law school.” Even at Syracuse Law, chosen mostly because his soon-to-be first wife, Neilia, was from upstate New York, Biden’s only academic goal was to avoid flunking out—which he barely pulled off.

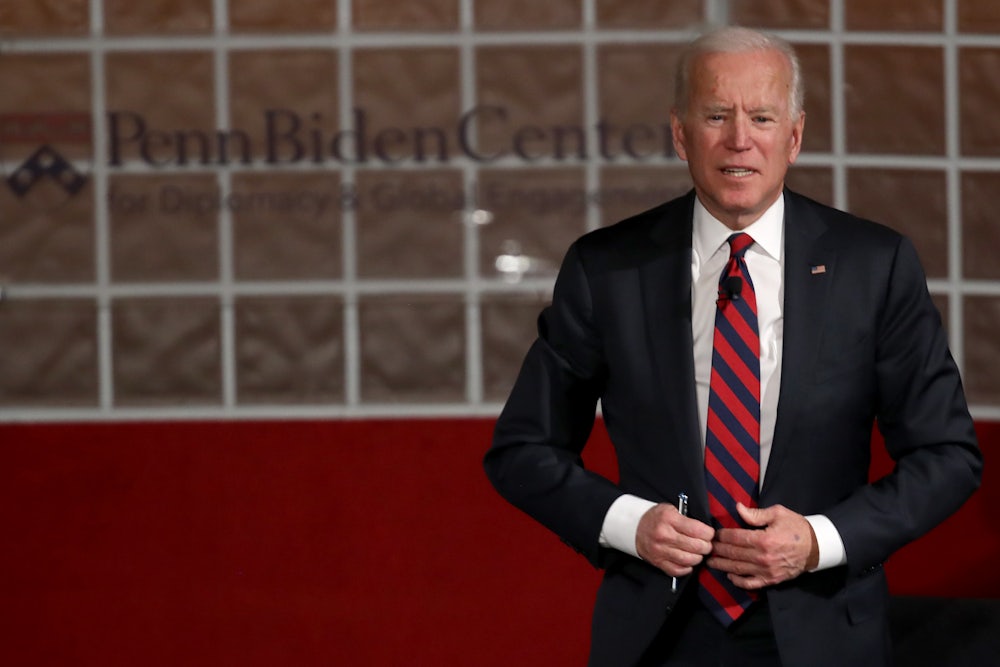

Maybe I’m expecting too much from Biden, but a small incident recently reported by Annie Linskey in The Wall Street Journal troubled me. Toward the end of a nuanced article about the president’s many, many ties to the University of Pennsylvania, Linskey revealed that one of Hunter Biden’s daughters was rejected for early admission to Penn in 2019. That setback prompted Biden—then a private citizen about to declare for the presidency—to speak to the dean of admissions at Penn. Probably not coincidentally, Biden’s granddaughter ended up among the 7 percent of applicants eventually admitted to Penn in 2019.

In a world of overhyped fake scandals—where everything is the greatest outrage since Aaron Burr killed Alexander Hamilton—this is a nothing-burger. Many politically connected parents or grandparents have put a thumb on the scale in the effort to score an edge at a prestigious college. Jared Kushner’s father pledged $2.5 million to Harvard before his son, despite shaky grades and SATs, was miraculously admitted to the school. As an extreme example, the FBI snared leading Hollywood figures in its “Varsity Blues” scandal built around the children of the powerful being admitted to selective colleges based on bribes and fake claims of unusual talent in minor sports.

But still, even after adding all the context in the world, this is not a good look for the president. Perhaps Hunter Biden’s daughter would have gotten into Penn on her merits during the regular admission period, but thanks to Grandpa Joe’s intervention, we will never know. In all likelihood, someone else was denied admission to Penn so there would be a slot for Biden’s granddaughter. For Biden, the incident is a reminder that a great strength (his tragedy-marred love of family) can also be a great weakness (his indulgence for Hunter’s dicey business dealings in Ukraine and China).

Biden’s intervention with the dean of admissions at Penn also provides a window into the president’s thinking about power and privilege in America. It connects with a story in What It Takes, which was a book that Biden so loved that he spoke at a 2013 memorial service for its author at the Columbia Journalism School. Sometime in the late 1970s, after Biden had been in the Senate for a few years, he was hanging out in a Wilmington backyard with longtime friends. Out of nowhere, Biden began talking about how he had learned in Washington that “there’s a river of power that flows through this country.” With passion in his voice, Biden explained, “Some people—most people—don’t even know the river is there.... And some people, a few, get to swim in the river all the time.” And then Biden moved in for the clincher, “And that river flows from the Ivy League.”

Despite his dedication to returning to Delaware on Amtrak every weekday night so that he could be with his growing sons, Biden also accepted the credo of the Washington elite. Biden made sure that his children would always swim in that Ivy League river of power. Beau Biden attended the University of Pennsylvania as an undergraduate, Hunter Biden received his law degree from Yale, and Ashley Biden earned a master’s degree in social work from Penn. It is an unalterable truth of life in supposedly meritocratic America—the powerful and the connected want to pass their privilege on to their progeny. And, as Biden recognized nearly a half-century ago, the Ivy League and a few similar schools embody the yellow brick road in America.

Sometimes, these graduations of educational power seem ludicrous. When the always loathsome Ted Cruz was a law student at Harvard in the 1990s, he would only work in study groups with fellow graduates of Harvard, Yale, or Princeton. Lesser Ivies, such as Penn, were beneath Cruz’s contempt. The scary thing is that Cruz may have been right in careerist terms. A new study has discovered that students whose undergraduate education was at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton are disproportionally likely to become Supreme Court clerks, no matter where they went to law school or their grades there.

So much of this privilege is never directly acknowledged. And it will get far worse if the Harvard-and-Yale-dominated Supreme Court, as expected, overturns affirmative action before the end of the current session in June.

Colorful Texas Democrat Jim Hightower got it right at the 1988 Democratic convention when he declared that Vice President George H.W. Bush “was born on third base [and] thought he had hit a triple.” In late 1999, when his son, Texas Governor George W. Bush, was running for president, The New Yorker published his Yale transcript. Interviewing Bush the following week aboard his campaign plane, I whipped out a tear-sheet from The New Yorker as I asked the third-generation Yale graduate about his 71 percent freshman grade in political science. Bush squinted at the transcript and noted with pride, “Twelve hundred college boards. Not half bad.” And then he looked at me, his fellow baby boomer, and said with an edge in his voice, “But I bet you did better, Shapiro.” My response: “Yes, I did, Governor. But I didn’t get into Yale.”

(Full disclosure about the allure of the Ivies: I’ve now spent the past decade as a lecturer in political science at Yale, based on my University of Michigan education.)

From time to time, Biden might have used the bully pulpit of the White House to remind Americans how corrosive this obsession with the Ivy League has become for democratic values. This important observation could have built on Jill Biden’s career boosting the virtues of community colleges. The president might have even pointed out that he received a fine education at a public university in Delaware. But instead, Joe from Scranton is like every other anxious parent and grandparent seduced by academic prestige. Something is wrong when even the president believes that in contemporary America you can no longer truly succeed on merit alone.