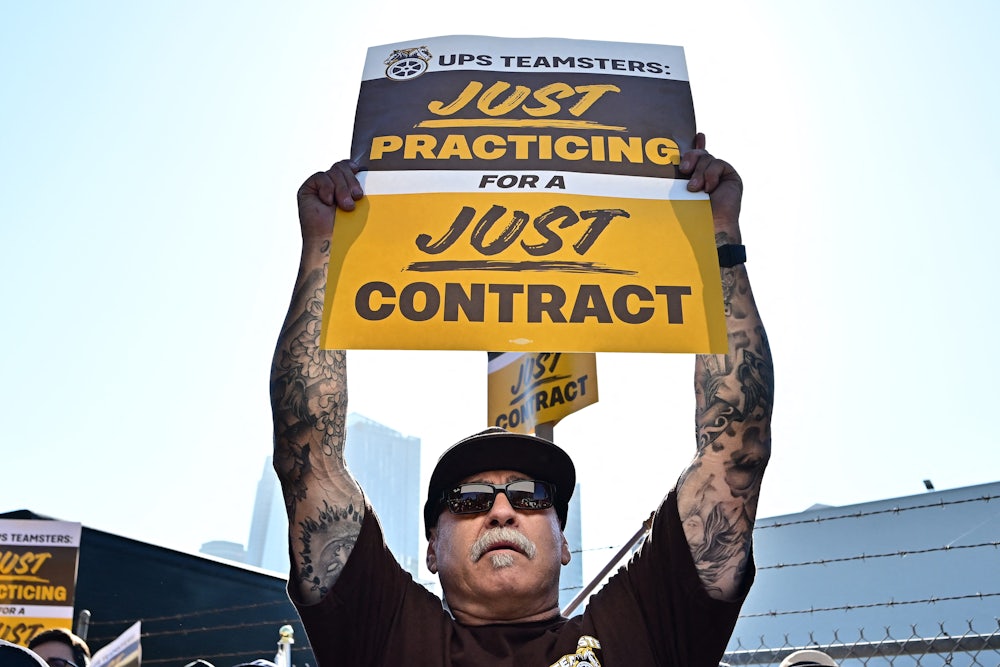

The United Parcel Service’s tentative agreement with the Teamsters on a five-year contract for 330,000 drivers and package sorters boosts starting hourly pay for part-time workers to $21, an increase of nearly $5; will increase hourly pay for existing workers by $7.50 between now and 2028; and guarantees that new vehicles purchased starting next year will be air conditioned. The contract, which must be ratified by union members, is the largest private-sector collective bargaining agreement in North America and, according to Teamsters General President Sean M. O’Brien, “sets a new standard in the labor movement and raises the bar for all workers.” Regrettably, it doesn’t set a new standard for UPS’s principal rival, FedEx Ground.

FedEx Ground drivers aren’t unionized; neither are about 40 percent of the workers at UPS’s second-biggest rival, DHL. But the main reason the UPS deal won’t raise the bar for FedEx Ground drivers is that FedEx Ground doesn’t, strictly speaking, have any drivers. This is achieved through a pernicious business model that David Weil, dean of Brandeis’s Heller School of Social Policy and Management and former wage and hour administrator in President Barack Obama’s Labor Department, termed, in a 2014 book that I seem to reach for more than any other, “the fissured workplace.”

To say that FedEx Ground doesn’t have any drivers is not to say that FedEx Ground drivers don’t exist. No doubt you’ve seen them on your doorstep. They wear uniforms with the FedEx logo and drive up in vans with the FedEx logo. But these drivers are, in a sense, an optical illusion. They’re FedEx drivers, but they don’t actually work for FedEx. They’re gig workers (“independent contractors”) or employed by small-business contractors. The business lobby’s fears that Julie Su, President Joe Biden’s nominee for labor secretary, will challenge this bait and switch is why Republicans (and some Democrats) are blocking her nomination in the Senate, just as they blocked Weil’s nomination last year to resume his former wage and hour post at the Labor Department.

FedEx Ground is not the same thing as Federal Express (later shortened to “FedEx” because who has the time these days for five syllables?). FedEx, founded in 1973, is the air service known for one-day package delivery when it “absolutely, positively has to be there overnight.” This service proved so successful that in 1998 FedEx created a subsidiary, FedEx Ground, to provide cheaper delivery of packages that didn’t absolutely, positively have to get there in one day, or even two. The idea was to put UPS out of business. Both FedEx Ground and UPS deploy drivers, but at UPS the drivers are employees who’ve been unionized since the 1930s. At FedEx Ground, because drivers are independent contractors, FedEx doesn’t have to furnish them with Social Security or unemployment insurance, or even pay minimum wage, as required by law when workers are employees. Or the drivers are employed by an intermediate contractor, which means that complying with all those laws becomes somebody else’s headache. For FedEx back in 1998, this model was, as Oliver North said about funding the Contras illegally through secret arms sales to Iran, a “neat idea.” It was less so, of course, for the people who deliver packages for FedEx Ground, who today earn less than half of what UPS drivers make, even without the new contract.

The state of California has lately been cracking down on the misclassification of employees as independent contractors through its 2019 law, Assembly Bill 5. The law imposed a strict new “ABC test” for determining whether a worker really is an independent contractor. Is the worker “free from the control and direction of the hiring entity”? Does the worker perform work “outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business”? And is the worker “customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business”? For FedEx drivers, the answer to all three questions is pretty clearly “no.” Su’s nomination is opposed primarily because she was California’s labor secretary when A.B. 5 was passed. The law was overturned by California voters in 2020, then reinstated in Superior Court, then overturned again by an appeals court and now awaits final disposition by California’s Supreme Court. The Labor Department, meanwhile, proposed in October its own regulation governing worker misclassification, one that explicitly rejects the ABC test because that would violate a ruling by the Supreme Court. That didn’t prevent Su’s opponents from claiming she’s itching to impose A.B. 5 on all 50 states, thereby blocking her nomination (though not her continuing presence as acting secretary, which, due to a law that applies only to acting labor secretaries, is not, the Biden administration says, time-limited by the Federal Vacancies Act).

It isn’t clear that a new Labor Department regulation or, in California, the ABC test, is needed to find FedEx Ground’s policy toward its drivers in violation of labor law. For years the courts and the National Labor Relations Board have gone back and forth over whether FedEx drivers are employees or independent contractors. The matter never seems to get resolved in any permanent way, but in June the NLRB issued a ruling that, by implication, says FedEx Ground drivers are employees and therefore, crucially, able to unionize. When FedEx Ground drivers work for a contractor that employs many FedEx Ground drivers, the arrangement resembles the franchising model. These small businesses have complaints of their own about FedEx Ground. One of the larger “franchisees,” a Nashville-based contractor named Spencer Patton, who employed hundreds of FedEx Ground drivers, complained last year that FedEx was expanding profit margins at small-business contractors’ expense. To discuss this and other matters, Patton created a trade association for other small businesses employing FedEx drivers. In response, FedEx canceled Patton’s contract and sued him for spreading what it said was misinformation. The lawsuit was dismissed in April.

One cheering fact is that FedEx’s attempt to put UPS out of business hasn’t worked. Not only is UPS still here, it’s roughly twice as profitable as FedEx Ground. There are advantages, it turns out, to employing drivers rather than treating them as independent contractors or the employees of small-business contractors. When Covid hit, for example, FedEx Ground found that its drivers were just independent enough to stop driving and isolate at home, along with much of the rest of the country. As a result, FedEx Ground struggled to deliver packages. UPS did not experience comparable difficulties with its union drivers.

But FedEx isn’t UPS’s only problem. “The competitor that I think is the destabilizing one,” Weil told me, “is less FedEx than Amazon,” and specifically Amazon Flex, a crowdsourcing delivery service created in 2015. Depending on how you calculate, Amazon Flex drivers can net as little as $5 an hour, according to a 2018 report by David Vernon, an analyst at the brokerage firm Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. Meanwhile, FedEx, whose hopes to expand market share through a UPS strike were dashed by the tentative contract agreement, is preparing to combine FedEx Ground with the overnight-delivery division (which now goes by the redundant-sounding “FedEx Express”). Unlike FedEx Ground, FedEx Express has always employed drivers, and those jobs will likely be eliminated in the consolidation. The fissured workplace isn’t done trying to kill off UPS and the union-labor model it represents. That it’s failed thus far doesn’t mean it won’t prove a threat in the future.