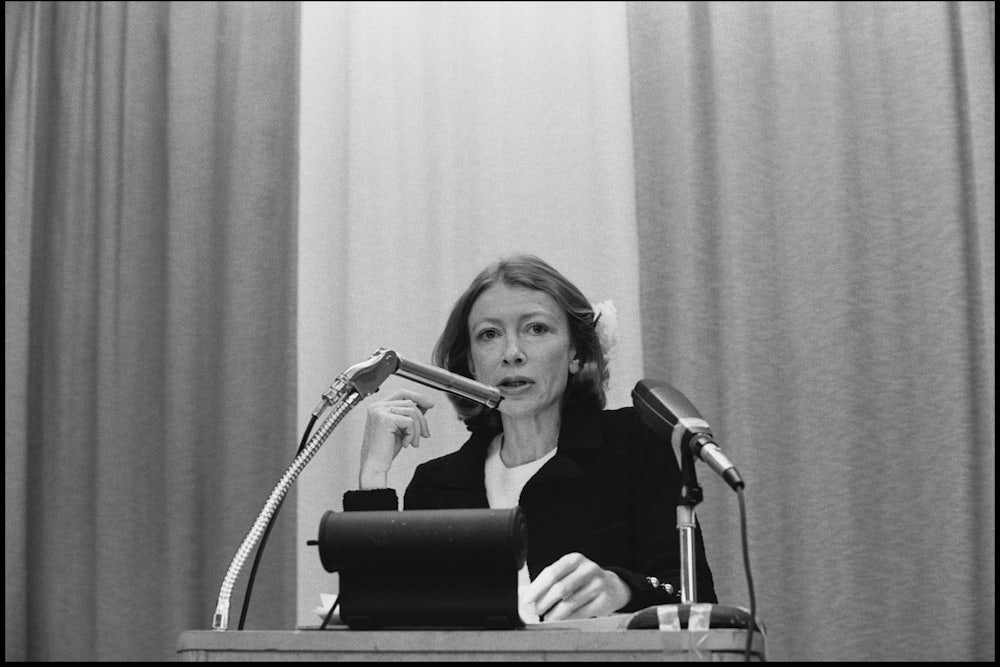

Joan Didion has had a startlingly active afterlife. A star-studded memorial, a pricey estate sale, an underselling Upper East Side co-op: In the almost two years since her death at age 87, much has been said about the queen of New Journalism—good, bad, and unctuous. The lifestyle coverage can be both a distraction and a deflection from the serious substance of Didion’s reporting on topics from the Central Park Five to wartime atrocities in El Salvador. More than the sunglasses or art collection, this journalism—for publications from The New Yorker to the Los Angeles Times, but mostly in The New York Review of Books—is a major part of her legacy. Her thoroughly researched and meticulously written analyses of the politics, personalities, and issues of her day should be studied as antidotes to the punditry of the 24-7, 280-character news cycle, in this age when truths are even stranger than “political fictions.”

Beginning in the 1980s, Didion did at the The New York Review something that very few women reporters had been allowed to do when she began her career decades earlier, when they were confined to fashion magazines or research departments: She covered campaigns and conventions, presidents and vice presidents. In 1968, she had written about Ronald Reagan’s wife, Nancy, back when he was governor of California, and in 1977, her topic was the empty mansion he built on the outskirts of Sacramento. In 1989, she took on the president himself.

The Reagan article, “Life at Court,” is a think piece reflecting on the legacy of his two terms based on recent books. The year prior, Didion did weeks of legwork, not just brain work, covering the presidential primary in California and the Democratic and Republican conventions in Atlanta and New Orleans. Her resulting article, “Insider Baseball,” analyzed the deep disconnect she experienced between both parties and the people they are supposed to represent. The candidates, she wrote—she barely deigned to speak George Bush’s or Michael Dukakis’s name—“tend to speak a language common in Washington but not specifically shared by the rest of us.”

Robert Scheer traveled with Didion as part of the press crew on these campaigns. At the time, he was a reporter for the Los Angeles Times and an outspoken, contrarian journalist himself. He found his colleague to be a fierce and fearless road warrior. “The times that I was alone with Joan traveling, I didn’t think of her as frail,” he says. “I thought of her as quite feisty and capable of surviving quite well and having a sharp eye and also keeping up the schedule that was even more exhausting at times than I wanted to do. What I loved about Joan was she had none of the pain in the ass qualities—the know-it-all, I can figure this out in 15 minutes arrogance—that a lot of journalists have. She always felt there was a lot to learn.”

Didion critiqued not just the two political parties but the entire system of political discourse, including policy advisers, pollsters, media consultants, and columnists: “that handful of insiders who invent, year in and year out, the narrative of public life.” Didion had a name for these invented narratives, which became the title of her 2001 collection: Political Fictions. “Insider Baseball” and its companion pieces don’t offer the sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll stimulation of Joan’s 1960s and 1970s writing, but they are equally insightful and arguably more important.

Political Fictions won the prestigious George Polk Book Award for “investigative work that is original, requires digging and resourcefulness, and brings results.” In her book Joan Didion: Substance and Style, the scholar Kathleen M. Vandenberg examines Didion’s later writings, beginning with Salvador, and argues that far from reifying and representing the ruling class, as other critics have charged, Didion sounded some of the earliest warnings of the Trumpocalypse to come. “She has, in both subject matter and approach, been amazingly prescient about the future of political and cultural discourse and the ways in which patterns of thinking and narratives of ‘fact’ are rhetorically constructed, and grounded both in the past and in the adherence to regional traditions and values,” Vandenberg writes. Joan warned us.

Didion’s writing style changed with the increasing complexity of her subjects. Her articles for The New York Review were much denser, less full of the “white space” she extolled in “Why I Write,” more linear rather than fragmented, and deeply, even maniacally, researched. Rather than giving in to the widening gyre, she was now determined to make sense of the world. She had a profound understanding of the importance of narrative, of finding order in disorder. “I mean total control has always been the reason I wrote anything at all,” she said in a 1972 letter to New American Review editor Ted Solotaroff.

Some of the change in Didion’s writing was mechanistic. Her switch to word processing programs allowed Didion to cut and paste passages in more complex and seamless ways than her old habit of arranging note cards on the floor. She wrote longer, in bigger paragraphs. She also turned less often to first-person narrative. She was now the well-informed expert offering her take on current events—an authority figure. These articles—“In the Realm of the Fisher King,” “Times Mirror Square,” “The West Wing of Oz”—don’t offer the same lyrical, conversational prose of the pieces gathered in Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album. They provide a different kind of pleasure: the thrill of a thorough, precise, relentless, and often unexpected interrogation. (“We are in an interrogation room, and I am interrogating Officer Gerrans,” Didion wrote in “Slouching Towards Bethlehem.”) And every now and then, she still gets in a jab so clever and/or ironic, it makes you laugh out loud, such as this one at Reagan in “The West Wing of Oz”: “Two hours before his 1981 inauguration, according to Michael Deaver, he was still sleeping. Deaver did not actually find this extraordinary, nor would anyone else who had witnessed Reagan’s performance as governor of California.”

Poet Michelle Bitting draws frequently on Didion’s prose for its weaving of incisiveness and insight. “There’s so much in it, and yet it never feels laborious to read, you never zone out on all of the information that she’s giving you,” she says. “I think she knows how to press into the facts and then pull back to the personal. And all the tangents, but it never feels like, ‘Oh I’m lost.’ There’s a music to it. But it’s so clear too.”

Didion wrote with the kind of authority historically allowed mostly to men. But she brought additional insights that the men could not, shaped by gender and her upbringing in Sacramento. “Clinton Agonistes,” an article about President Bill Clinton’s sex scandals and impeachment hearing, opens thus: “No one who ever passed through an American public high school could have watched William Jefferson Clinton running for office in 1992 and failed to recognize the familiar predatory sexuality of the provincial adolescent.” As someone who attended a provincial American public high school and watched Clinton shake hands at a New York rally in 1992, I can only respond, “Exactly.”

The bravery of Didion’s genre innovations throughout her career created whole new ways of writing; without them, untold numbers of readers might not have become writers. David L. Ulin is an author, professor at the University of Southern California, former book editor at the Los Angeles Times, and editor of the Library of America editions of Joan Didion’s work. “There’s a real present tense quality to that writing, in the sense that I always have the notion, even when I reread it now, of her in the moment trying to figure it out,” Ulin says. “It’s polished, but I almost feel like I’m watching the movement of her thinking … I’m always aware of her uncertainty, of what she doesn’t know as much as what she does know.”

Postmortems tend to praise Didion as a stylist. If by “style” they are referring to her intrepid interrogations and rigorous, luminous prose, then yes, she was one of the greatest of them all.

Excerpted from The World According to Joan Didion by Evelyn McDonnell and reprinted with permission from HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright 2023.