I came to Joan Didion backwards, starting with the wry and savage essays of Political Fictions, and only later working my way backward through her oeuvre. It began in 2001. I was in college. It’s hard to remember now the terrifying political unanimity of that moment, the way that the deep popular cynicism and indifference of the post–Cold War, post–Clinton scandals evaporated on September 11, replaced by a furious national identity that couldn’t brook the slightest deviation from a newly (at least, newly open) warlike national purpose. I was 20, a wannabe radical and political leftist, barely recovered from my more problematic adolescent dalliances with tendencies that we would later come to call the alt-right or the post-left. Political Fictions, which combined the aristocratic disdain for which Didion has been criticized (sometimes rightly, sometimes unfairly) with the needlepoint precision of observation and description for which she has been lauded, provided a diagnostic framework through which to view the great disruptions of the Bush era in continuity with the stage-managed spectacle of American politics that had preceded it. It was also very funny—especially the chapters on journalist Bob Woodward and Former U.S. House Speaker Newt Gingrich—a quality that Didion’s critics and admirers both often underrate. It is astonishing to reflect that this weary, hilarious, incisive book was first published in America only a week after 9/11.

Loving a writer is often a matter of a fortuitous first encounter. I’m very glad this was mine. I think if I’d initially run into Didion via her famous early works, if some creative nonfiction class had tasked me with reading the deliberately mannered and self-consciously New-Journalistic essays of Slouching Toward Bethlehem and The White Album—“all that princess-in-the-consulate bullshit,” a friend of mine, less of a fan than I am, once called it—then I would have been turned off and might never have returned. I would have found it precious and high-handed, and I would have found its best-known bits of self-reflective revelation, the “here on this island in the middle of the Pacific in lieu of filing for divorce”–bits, calculated and artificial. I think I would have found her phony.

Instead, I read the essays in what amounted to reverse-chronological order, and so my perspective on the output of the sixties and seventies was to see a working-out and expurgation of a lot of “fixed ideas,” to use one of Didion’s own titles, and the gradual development of a style of writing into what would become a style of thought. Didion is, of course, inextricably linked to the idea of a style. An interest in the merely superficial is something else for which she’s often been criticized—unfairly, I think. For all the recognizable stylistic consistency of her prose across the decades of her career, it takes an intentional lack of generosity to miss the evolution of her writing and of her thought. In the essay “In Bogotá,” for example, written in 1974 and collected in The White Album in 1979, she remembers her time in a place that had experienced the violent expression of America’s Monroe Doctrine as “mainly images, indelible but difficult to connect.” That essay contains barely a whisper of what would become, a decade later, in Salvador, a far more searching, searing examination of the brutal consequences of American influence and interference at the peripheries of its global empire.

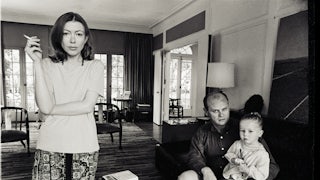

Popularly, The Year of Magical Thinking, the first of Didion’s two late-career “grief memoirs,” wrenched her image from the vitrine-like preservation of the woman in sunglasses, with the cigarette, leaning against the Corvette, into something more fully human, more embodied, capable of emotion, frail, and subject to the passage of time. But in my mind, the preceding book, Where I Was From, most explicitly and most intelligently examined her sentimental and intellectual transformation over the course of her life and career: “an exploration,” she called it, “into my own confusions about the place and the way which I grew up, confusions as much about America as about California, misapprehensions and misunderstandings so much a part of who I became that I can still to this day confront them only obliquely.”

That last phrase is a bit of writerly misdirection. She confronts misapprehensions and misunderstandings quite directly. Didion was from Sacramento, from an old, fairly prosperous California family. Some of her ancestors had travelled West with the Donner party. She was raised to believe in a story of frontier independence and agricultural self-sufficiency—a religion of unfettered yeomanry with roots in the earliest Jeffersonian ideas about the American republic, which found its apotheosis in twentieth-century California before the social convulsions of the latter third of the century. And even over the course of her career, as her own youthful Goldwater conservatism was tossed by the shoals of the counterculture and her own midlife anomie, as it broke up on the rocks of Ronald Reagan’s sublime idiocy and the shocking crimes of the Iran-Contra scandal, one sensed that she was not quite ready to give up the ghost of that California entirely. Until she did.

Where I Was From ranges from the “pioneer” Anglo settlement of the state—then, as now, dominated by huge landholdings, speculation, and an industrial form of agriculture—to the massive environmental engineering of the Sacramento Valley, from her personal family history to the defense industry–subsidized (and, later, defense industry–abandoned) suburbanization of Southern California. It reexamines California as a massive project of federal investment, and therefore a project of American imperial ambition in its own right. (She is never unconscious of the fact that California itself was a part of Latin America until the U.S. decided to incorporate it.) Among other reexamined illusions, it contains an embarrassed, even angry, reassessment of a novel called Run, River, by one Joan Didion—her first novel. Didion was an Episcopalian of a sort, although her own mother had refused communion and professed herself incapable of believing in the divinity of Jesus, but was never especially religious in her writing. Nevertheless, I find that Where I Was From reads almost as a narrative of conversion—or, maybe, of repudiation: the discovery, after a lifetime of unthinking faith, that the same lifetime’s worth of steadily accumulating doubts suddenly rolls down the mountainside and drowns out the old, mumbled liturgies.

This is the least appreciated of Didion’s qualities, but I hope it is the one that receives the most examination and reexamination now that she has died. It would be a shame if her legacy is only the rhythmic subtleties of her prose. There have been more radical political transformations, certainly, and more complete changes in an author’s style across decades-long careers, but I think there have been few more interesting evolutions. The self is always to some degree an essayist’s only real topic, but Joan Didion was, at her very best, able to perceive and represent her own self as a metonym for a larger American experience of history as a dream from which we have to wake up in order to write it down.