There was never any doubt that America’s influential band of Christian Zionists would embrace the Gaza war with enthusiasm. Three days after Hamas committed its infamous October 7 atrocities, the most prominent Christian Zionist of all, John Hagee, founder of Christians United for Israel, delivered an ecstatic YouTube sermon. “Good morning, America and the world,” he boomed in his finest Cronkite, “Israel is at war.” This was a battle between good and evil, Hagee said, before vowing to “lift up their warriors and leaders in prayer.”

But some evangelical Christians are looking to uplift with far more than cosmic invocations. Overwhelmingly supporters of Israel both politically and spiritually, some of the most strident of these advocates are using the war to proffer something that is more often left unsaid: In order to fulfill the prophecies these Christians hold most dear, Jews must convert to Jesus. And while the idea of bringing Jews into the tent is as old as Saint Paul the Apostle, it’s not simply American Jews that some of the more nefarious evangelicals are seeking to convert—it’s Jewish people in Israel, the ultimate supersoldiers for their holy mission.

One figure in this milieu particularly stands out. Curt Landry, described by one Israeli writer as “sometimes ‘Pastor’ sometimes ‘Rabbi’ but always missionary,” ministers to a congregation of around 100 in rural Oklahoma—but his true mission field is a long way from the prairies.

Shannon Nuszen, a Jerusalem-based former evangelical Christian missionary turned Orthodox Jewish convert runs an organization called Beyneynu, which monitors foreign missionaries targeting Jews as converts. She recently received a complaint from an Israel Defense Forces soldier on duty in the Gaza war, who claimed that a campaign of proselytizing was underway, seeking to convert Israelis fighting on the front lines.

“His unit was visited by a group of missionaries who brought donations,” she told me, supplying evidence. The soldiers were given a copy of Landry’s book, Reclaiming Our Forgotten Heritage: How Understanding the Jewish Roots of Christianity Can Transform Your Faith, which outlines a way that Jewish people can come to Jesus through what’s called the “One New Man” doctrine. “The representative explained to the soldiers that if they would agree to be photographed with the book, the ministry would continue to provide donations to the IDF.”

Landry’s own website boasts about these efforts. “Reclaiming Our Forgotten Heritage book distribution project inspired 10,000 IDF soldiers,” it says. Further distribution “will bring hope to 12,000 more! Keep the prophetic momentum going.” Each $20 donation to Curt Landry Ministries, it says, gives an IDF soldier a copy of Landry’s book, a hat embroidered with their unit logo, and a bookmark that takes them to a site “that answers their [frequently asked questions].”

Curt Landry doesn’t have John Hagee’s sway in Washington, but his ministry is doing the kind of work that the Hagees of the world cannot. His House of David church in Oklahoma is a Messianic Jewish church in all but name, and Landry’s practices and preaching undoubtedly count him as belonging to this controversial branch of evangelical Christianity—one that is finding new energy in the darkest of times.

Churches labeled as Messianic Judaism have been around since the 1960s, when the charismatic wave of Pentecostalism found new converts through the Jesus People movement that was wildly popular in California. Wearing hippie clothes and producing great music, the Jesus People swept a generation disillusioned by the Summer of Love off their feet. Many of those the Jesus People sought to bring into their fold grew up in Christian homes, but there was a small cohort who grew up in Jewish households too. The latter became known as “Jews for Jesus,” and while they found many converts, in time, a growing number of non–ethnically Jewish people became enamored with finding a way of celebrating Jewish customs while celebrating Christian faith.

Messianic Judaism might follow laws of the Torah, observe Shabbat, and even undertake circumcision, but the ultimate belief that believers must accept Jesus as their savior means that they are not recognized by any of the major Jewish denominations. However, a growing number of mainstream Jewish media, political, and even religious figures are happy to break bread with these congregations, thanks to their unswerving political support for the state of Israel.

Today, there are an estimated 175,000 to 250,000 Messianic Jews in the United States, and some 350,000 worldwide, with a small minority living in Israel. Though Messianic Jews identify as “Jewish Christians,” around half of those attending Messianic services in America are not ethnically Jewish.

Nuszen’s tip-off piqued my interest, because back in 2021, I visited Curt Landry’s House of David, a sprawling mansion outside of Fairland, Oklahoma, to see the modern expression of the movement for myself.

Instead of worshiping on a Sunday morning like most Christians do, House of David conducts its primary service on Friday night, in line with Jewish custom. An amped-up band opened with standard white evangelical devotional music, before a group of men led by a guy in a “WRSHP” baseball cap were called to the altar. There, they raised ceremonial shofar horns into the air and blasted tekiah: a long, deep sound that calls people to attention.

Smooth and syncretic as they come, Landry urged his people to “flow into Sabbath and surrender to the Holy Spirit within, where the supernatural happens: miracles and healings.” It was an unusual experience, to say the least, in a part of the world where traditional Jews aren’t exactly plentiful. Listening to the service, it felt at times as though the congregation worshiped the modern state of Israel as much as it did Jesus.

Landry and his fellow Messianics would argue that this is exactly the point. He rejects the label, writing, “We are an evangelical congregation made up of both Jew and Gentile Believers.” But for all intents and purposes, Curt Landry Ministries is a Messianic Jewish church—and it is at the vanguard of a global, highly political movement with unquestionable evangelical sympathies.

Squaring this merger of evangelical practices with Jewish appearances has been made all the more difficult by a long history of subtle antisemitic tropes existing alongside philosemitic beliefs in the evangelical movement.

A 1972 White House meeting between President Richard Nixon and evangelist in chief Billy Graham—a bog-standard Southern Baptist but one who is revered by Landry—laid these contradictions bare. The Jews “swarm around me and are friendly to me because they know that I’m friendly with Israel,” Graham told Nixon. “But they don’t know how I really feel about what they are doing to this country. And I have no power, no way to handle them, but I would stand up if under proper circumstances.”

The next year, during the Yom Kippur War, Graham campaigned for the largest airlift in U.S. history to aid Israel. His subsequent “Key 73” evangelism campaign made a landmark statement opposing “all forms of coercion, intimidation and proselytizing” to Jews. It heralded a new era of Christian Zionism, where evangelicals would give full-throated support to the state of Israel and ask for nothing in return.

That is to say: in theory, at least. Graham paved the way for the evangelical movement to understand the Jewish people. Usually spoken in hushed terms, this has become far louder since the outbreak of the Gaza war. There are “good Jews”—Israelis going into battle at the ultimate frontier—and “bad Jews,” who are left-wing, college types in the West, espousing socialism and protesting the repression of Palestinians.

“God’s Machine Gun,” as Graham was known, might have established a widespread embrace of Christian Zionism among American evangelicals, but Landry’s work in the Holy Land highlights that for the messianically inclined, political support is a means to an end—specifically, The End.

Landry promotes the One New Man doctrine, which one early proponent described as an “approach in partnering with” those early Messianic Jewish converts. Dr. David Rudolph, director of Messianic Jewish Studies at The King’s University in Texas, offers One New Man as a vehicle for Christians looking to understand their relationship to Jews and Judaism but who “find it difficult to know which directions are healthy” and, critically, “which lead to weirdness.”*

The idea of One New Man comes from a verse in the New Testament book of Ephesians 2, which outlines a vision of Jews and Gentiles finding peace with each other through the Messiah, healing the schism between Christians and the Jewish people—albeit, through the church.

For he himself is our peace, who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility, by setting aside in his flesh the law with its commands and regulations. His purpose was to create in himself one new humanity out of the two, thus making peace, and in one body to reconcile both of them to God through the cross, by which he put to death their hostility.

Understandably, many practicing Jews might think that this looks a lot like supersessionism, or replacement theology. This was an idea developed in antiquity that holds that Jews were replaced by Christians as God’s chosen people and that the promises made to Israel in the Bible are fulfilled through the Christian Church. As professor Mika Ahuvia, a scholar of early Judaism, wrote in the wake of the Pittsburgh Synagogue shooting, it was only after the Holocaust that people began acknowledging that supersessionist thinking had “violent real-world implications.”

It is simply unconscionable for modern Christians to preach such a theology, but it is easy to see how it gave birth to One New Man. Still relatively obscure in mainstream Christian theology, it is an idea that vibes with the direction of evangelical thought.

For Landry, One New Man is not simply a way of doing church: It’s personal. An adopted kid who was “bitterly disappointed” with the man who raised him, he discovered the Jewish roots of his birth parents and set about forming a ministry that combined his upbringing with his heritage. The ministry he founded in 1996 combines signs and wonders of charismatic Pentecostalism with a quest “to be a bridge of unity and restoration between Israel and the Church.”

As someone who has watched Landry’s ministry for some time, it is clear that he has a deep reverence for Jewish customs and the Jewish people. But Landry and One New Man devotees remain deeply evangelical Christians—and with that comes a conception of the End Times that requires Jews to accept Jesus in order to avoid eternal damnation.

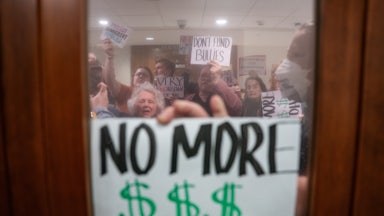

And while sometimes these sentiments get mired in the text, they eventually spill out into the open. Last year, Landry outraged some Israelis by erecting a statue in the Golan Heights that depicted a menorah on top of a Star of David, all being held up by a Jesus fish. The statue, which was removed after the outcry, came on the back of other instances of other Christian groups reportedly infiltrating Jewish organizations in Israel. It led to some members of the Israeli Knesset attempting to pass a bill making religious proselytization punishable by jail time, which was eventually shot down by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who didn’t want to upset American allies.

Landry’s efforts might be a minor skirmish at a time of immense suffering in Gaza, but that evangelicals feel empowered to try to convert Israeli soldiers while they are at war highlights calculations that go well beyond religious lines. Shannon Nuszen says that it is “beyond comprehension that evangelical Christians, who call themselves our closest friends, would capitalize on the pain and uncertainty that has engulfed the Middle East to peddle this unwelcome message.”

Landry’s latest effort shows that, among evangelical Christians of varying stripes, there is an unwavering belief that the Jewish soul must be salvaged, the ultimate prize: If only they understood what is otherwise in store for them. Israel, the nation and all who could call it home, are not merely great allies and custodians of the Holy Land but a counter to Western decadence.

Common ground may have been opportunistically forged in a secular sense between highly political Christian and Jewish leaders invested in Israel overcoming the Palestinian people, but there’s a reason why we don’t see One New Man espoused by Jewish rabbis. Landry and his cohort may provide overt support for Israel, but it’s also where his syncretic faith, which fetishizes Judaism and the Jewish people, becomes creepy. For all of the shofars and tallit prayer shawls, the One New Man doctrine ultimately holds that Jews must submit to Christianity before the End Times—with the war in Gaza serving as a sign from above that it might be happening very soon.

* This article originally misidentified Dr. Rudolph.