May 2018 was a pivotal moment for people we might now call “anti-woke” thinkers. When Bari Weiss put together a feature on “the Renegades of the Intellectual Dark Web,” writers and academics who churned out books and blog posts on political correctness suddenly acquired the sheen of glamour that comes from having a forbidden or dissident point of view. The piece, which profiled “a collection of iconoclastic thinkers, academic renegades and media personalities” who felt “locked out of legacy outlets,” ran with moody portraits of the likes of Joe Rogan, Eric Weinstein (then managing director of Thiel Capital), and Michael Shermer (publisher of Skeptic magazine). The group bemoaned the “siege” on their perverted sense of free speech. But their thought crimes also seemed to be serving them pretty well.

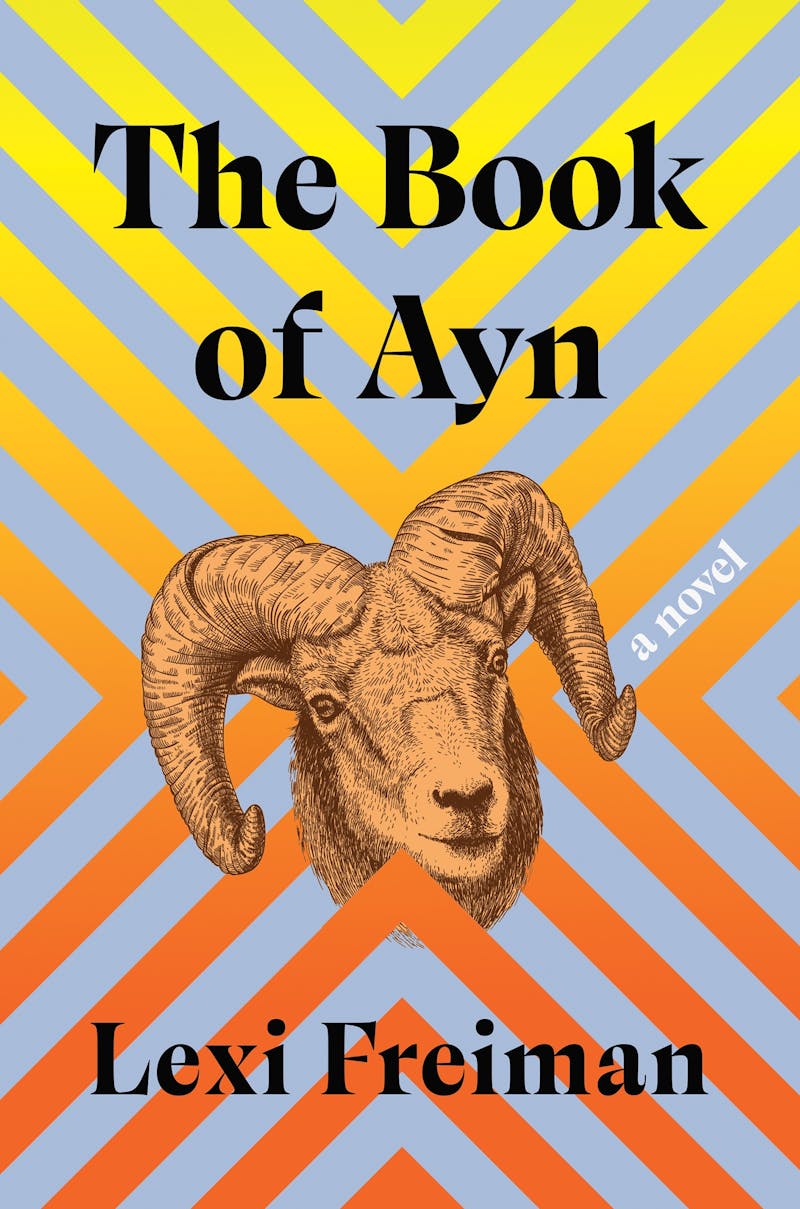

Like the Intellectual Dark Web’s mavericks, Anna, the 39-year-old protagonist and narrator of Lexi Freiman’s rollicking satire The Book of Ayn, is addicted to “the verboten,” to “the dizzy zing of the counterintuitive” and the attention that airing it brings. Anna believes that her contrarianism has gotten her canceled—The New York Times has panned her new novel, a satire of the opioid epidemic that she wrote in a family friend’s Madison Avenue pied-à-terre, calling the book “classist” and deeming Anna a “narcissist.” Anna also studiously avoided the trauma plot, to the chagrin of the Times, which accused her of “under-contextualization.”

Wounded by the Times and dropped by her publisher, Anna slides not into the alt-right, but into the rational selfishness of Ayn Rand. Smarting after being shunned by the literary collective, she soothes herself with Rand’s philosophy of individualism, the sense that “being your own raison d’être resolved all questions of meaning and purpose.” At first blush, it’s an odd choice of hero: Rand isn’t even especially popular among the anti-woke set. Shortly after diving into Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead, Anna attends a “dissident soiree” in a West Village townhouse with the likes of “furloughed boomer editorialists, Black libertarian Substackers … and socially dysfunctional moderates out for a good time”—an updated Intellectual Dark Web. Even there, she can’t find fellow Rand fans. A pair of Dimes Square girls call Rand “a bit basic” and are quick to pivot to a man who might introduce them to Peter Thiel.

The Book of Ayn is not a novel that satirizes the Annas and Ayns of the world in order to sketch out a more compelling left-wing vision. Nor is the novel merely a satire. Freiman’s debut, Inappropriation, an irreverent take on identity politics in the package of a coming-of-age novel, proved her dexterity at picking apart sacrosanct stances while also plumbing the depths of the desire to belong. The Book of Ayn accrues similar layers: Anna’s tailspin becomes an epic hero’s journey through New York, Los Angeles, and Lesvos; a Künstlerroman of a novelist in a midlife crisis; a picaresque quest for meaning.

Freiman smartly sidesteps politics and polemics—mercifully, the novel never mentions Trump. She makes The Book of Ayn instead a novel saturated with avoided grief, wherein Anna must grapple with her record of “yoking myself to bad ideas since I was three years old”—the age when her baby brother died and she responded by smearing her own poop on her parents’ bedroom walls. Freiman presents a case against “The Case Against the Trauma Plot,” examining what Anna’s refusal to conform to narrative expectations in life and in art has cost her, and how she might find a path forward. In this, The Book of Ayn is both more and less transgressive than its title makes it seem; Anna’s provocative posturing serves as armor against pain.

Unlike much of the Intellectual Dark Web, Anna has a sense of humor about her cancellation. “Truthfully, I’d known that scatological humor was now banned from descriptions of the rural poor,” she explains. She was just trying to “bring a little slapstick to the ongoing national tragedy.” Perhaps her greatest thought crime was refusing to believe “that people were products of their circumstance.” Anna had chosen to make “certain characters selfish without explaining why. I had simply put them in their adult lives with a puppy and a bag of heroin.”

Anna is thus not so much a reactionary as an edgelord reveling in “the soft stuff of moral subtlety,” Freiman opting to take her on an absurdist quest for artistic and personal fulfillment, a quest that ultimately forces her to reckon with her own circumstances.

Freiman’s novel trots briskly across the globe but packs its two parts with scatology, philosophy, fertility, sex, a brief moment of virality, a woke Seinfeld remake, goat yoga, literal death and ego death, and a Greek commune that recalls the Rajneeshpuram of Wild Wild Country. The breakneck pace both affords comedic effect—Freiman works an outrageous line of dialogue or image into nearly every page—and enacts Anna’s spiral, as she flings her whole being into the embrace of one radical philosophy and then another. Anna gloms onto Rand and then onto “the truly spectacular pariah” who founded the commune in a mode that mimics the Intellectual Dark Web’s embrace of reactionary ideologies—she is attempting to revive her career after realizing that her original schtick is unsustainable. That the one thing she has been avoiding all along—the trauma of her brother’s death, which she doesn’t even believe belongs to her—might hold the key is obvious to the reader but repulsive to Anna.

Instead, she distracts herself with more immediate tasks: soothing her wounded ego and resurrecting her artistic brand. Reveling in the apparent originality of making a Randian worldview her entire identity, Anna flees Manhattan for Los Angeles. She’s connected with a manager who wants her to write a half-hour comedy about Rand, whose work she has barely had time to read, let alone comprehend. No matter—Anna, who loves a good paradox, believes she can cancel herself into a more lucrative career. She’s determined to write a “funny homage” to Rand that contains no trauma and no character arc. Freiman, who also writes for television, sends up the whims of the industry—the manager’s ask soon morphs into an hour-length animated historical comedy.

It seems for a moment that Anna might be able to deliver. In L.A., she serendipitously finds herself in an apartment building full of Gen Z-ers making micro-content for an app she mishears as being called “Jizz.” The app’s users apply animal avatar filters to “behave in ways that were off-limits to human beings.” While flirting with her neighbor, who uses a Labrador filter to “embody idiocy,” she allows him to film her babbling about Rand’s takes on “the empty moral center of altruism, the self-sacrificing impulse at the heart of socialism. The death drive, which I knew almost nothing about.” He applies a horned sheep filter; Anna becomes Ayn Ram, goes viral, and believes she’s found a way to transmute radical selfishness for a television audience.

When Anna is forced to admit that she’d been ignoring the fact that Rand can’t joke and that the virtue of selfishness was a bad idea at the root of “the emptiness of modern life,” she wallows momentarily in her own stupidity. In these scenes, Freiman gives depth to a character who might otherwise stall out as a troll oblivious to her own contradictions—depth that hinges on the dreaded backstory. Family matters call Anna back to New York, and Freiman extends the meditative moment for a few beats longer. Depressed and living with her disapproving mother, who keeps a “shelf of photo albums with their cluttered pages and all the little sinkholes of grief,” Anna seems on the verge of understanding what’s underneath her impulse to be contrary, to give credence to “the disreputable side.” She almost admits to her mother that she had wrapped herself in Randian self-interest because caring—about others, about anything—“felt like death, like disappearing.”

This is the expected emotional climax of the novel, but Freiman’s not done putting Anna through the wringer. Soon, a friend sends an email about an ego death workshop at a commune in Lesvos, and she’s off for an adventure that recalls “Eat Pray Love narrated by Humbert Humbert.” The relentlessness of Anna’s seesawing between revelations and self-deceptions in Lesvos gets a bit tiresome, as does her love affair with a barely legal Slav with blond dreads who wholeheartedly loves both the commune’s deceased Master and Tom Cruise.

Ultimately, though, this Greek jaunt serves to bring Anna back to her writing, which promises her a path forward. Anna’s quest across The Book of Ayn is for her next artistic project, one that doesn’t feel so empty at its core. In order to get there, she has to reckon, finally, with what’s been driving her rebellion against caring too much for or about anything but handsome young boys all along. That Freiman literally cakes Anna’s trauma narrative in shit—feces torment her across the novel—feels apropos. She is, after all, fucking with us.