In his 1949 essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” James Baldwin objects to fiction that seeks to say of Black oppression only, as Miss Ophelia does in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, “This is perfectly horrible! You ought to be ashamed of yourselves!” Harriet Beecher Stowe’s book was, Baldwin wrote, sentimental and self-congratulatory—using its characters to prove a point, without granting them the “undefinable, unpredictable” qualities of real people. “The protest novel, so far from being disturbing, is an accepted and comforting aspect of the American scene,” Baldwin observed. It assures the reader that “whatever unsettling questions” it raises have “nothing to do with us.” In fact, “we receive a very definite thrill of virtue from the fact we are reading the book at all.”

Ryan Lee Wong has taken on the challenge of writing a self-aware, critical version of the protest novel with his debut Which Side Are You On—a slim work that is literally about protests and activism, that manages to interrogate both the rigidity of movements and the complacency that can find its way into them. Wong’s novel follows Reed, a 21-year-old Columbia University student visiting his hometown of Los Angeles. Reed had been an “Obama liberal” who saw protesting as an “embarrassing, pointless performance” until the 2014 killing of Akai Gurley, a Black man, by Peter Liang, a Chinese American New York City police officer. Now, he’s ready to drop out of college to devote himself wholly to the Black Lives Matter movement. But over the course of the week—through conversations with his mother, whom he learns was a co-leader of South Central’s Black-Korean Coalition in the 1980s, and his father, a Chinese American union attorney who spent his twenties reading Gramsci and Mao—Reed starts to question his radical ideals.

At the outset of Which Side Are You On, which takes its title from the union protest song, Reed speaks in soundbites that recall Baldwin’s description of Miss Ophelia’s statement against racism: “Her exclamation is moral, neatly framed, and incontestable like those improving mottoes sometimes found hanging on the walls of furnished rooms.” Or, as Reed’s childhood friend puts it, “You sound like Adorno, if he, like, worked out his ideas on Twitter.”

The night he arrives home, Reed goes to dinner with his parents in Koreatown. When they try to talk to him about school, he instead offers his observations on the racial makeup of the restaurant staff—the waiters are Korean and busboys Latino, which he sees as “a clear example of racial capitalism.” Reed won’t allow himself to just enjoy the perfectly charred kalbi or the time catching up with his parents: “I just think we have to be aware of each interaction, or else we’re blindly upholding the white supremacist heteropatriarchy.” His father responds, “I see they’re teaching you something at Columbia,” Reed shoots back, “I learned about racial capitalism through Twitter and meetings, not Columbia. Everything in college is designed to insulate us from the world, so we can patch over the neoliberal order without challenging anything structural.”

Reed speaks with the certainty of the newly converted. He has only

recently pledged allegiance to cross-racial solidarity, in the process turning

his back on essentially every other aspect of his life, from his schoolwork

(he’s on academic probation) to his family. He has come to L.A. to see his

Korean grandmother, who had a stroke and is in a care facility—he had only

half-listened to his mother’s updates on her condition while checking Twitter.

He can’t bear to take his attention away from the movement because he feels

like he’s playing catchup; he sees himself as a “naive, privileged kid trying

to build my analytical parachute mid–free fall,” as though theories are a means

of deliverance.

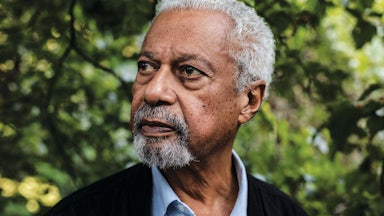

Wong is sympathetic to Reed’s idealism. Like Reed, Wong grew up in Los Angeles; his Korean immigrant mother actually was the co-chair of the Black-Korean Alliance, and his Chinese American father actually was a union attorney. And like Reed, Wong participated in Black Lives Matter protests against police brutality following the Gurley shooting. Which Side Are You On takes racial justice and the need for activism seriously. In a scene where Reed recalls marching across the Brooklyn Bridge to protest the lack of indictment in Eric Garner’s killing, Wong captures the immense grief undergirding the Black Lives Matter movement: “We must love and support each other, we chanted, because the system would kill you and blame you for your death. So we had to be there … if for nothing than to show each other that every lost life demands we pause the world for a moment.”

But Reed’s energetic pronouncements are not the moral center of the novel. Which Side Are You On revolves around a mother-son relationship and Reed’s struggle to understand why his mother is so critical of his style of activism. She sees her son’s methods of organizing as self-serious to a fault and knows just how poke holes in his self-righteousness. When Reed objects to the idea that self-care might be a necessary component of activism, his mother reminds him of how communities actually coalesce: “Organizing is person-to-person, right? And do most people like to sit around in meetings talking about blah-blah racial capitalism? Or do fun things, like sharing food, or exercising, or listening to music?” Much of the novel is spent driving around the city in her Prius (“Mom had finally broken her lifelong boycott against the Japanese colonizers because, she explained, the mileage was unbeatable, and anyway, we had to let go of that ancestral shit sooner or later,” Reed explains). The perennial L.A. traffic leaves ample opportunity for debates about activism and organizing.

Reed initially approaches these conversations with an eye toward extracting a perfect lesson from the Black-Korean Coalition to incorporate into a blog post, but his mother resists: “There are things I’m happy to share if they help you understand what you’re doing out there. But I’m not going to polish it into some tool kit you can circulate to your activist friends.”

Instead, she nudges Reed toward the same lessons she and his father had to learn as activists: on building trust and person-to-person relationships, on making space for joy, and on staying humble and forging forward even when you don’t win, when the revolution doesn’t come. She takes him to Roscoe’s Chicken & Waffles, where she used to eat with her coalition partner Bobby, a Black man who represented South Central. She takes Reed out to South Central, a neighborhood he had never actually set foot in, attempting instead to “understand this history at a safe, critical remove from the place, from the [people] right in front of me.” Gazing up at the Watts Towers for the first time, Reed realizes he feels like a tourist, that he actually does not know how to meaningfully be in solidarity with the Black community there.

The most important lesson Reed’s mother imparts, though, is also what she says is the “biggest challenge—figuring out your own people.” Reed has neglected to do so, out of fear that organizing fellow Asian Americans would only “take up space” and “be another subtle form of anti-Blackness.” When he protests with BLM, a parallel rally is also taking place, led by Chinese Americans who point out that Liang was treated differently from his white colleagues. Reed feels betrayed by “the tens of thousands” who support Liang: “They were ruining all the post-‘68 coalition building between Blacks and Asians, proclaiming that they didn’t want solidarity, they didn’t want to be people of color—they wanted to watch out for their own.” The result of his despair has been to pull away from his own identity: He realizes that he barely understands his own family’s history, especially on his mother’s side, down to the when and how and why of their emigration from Korea.

Crucially, for as much time Wong dedicates to cross-generational dialogue about organizing and history, he spends an equal amount of time capturing Reed’s physical makeover, grounding a heady novel of ideas in visible acts of self-reinvention. Reed’s mother imparts her lessons in exchange for dragging him to an early morning hot yoga class, to a Korean spa for a full body scrub, to a strip mall salon for a haircut to fix the crooked chop his activist friend gave him. By putting Reed through bodily discomfort—of crying with relief at the end of the yoga flow, of laying like a “specimen” on a spa table, of “being lathered up like a prize dog” while his friends are protesting Liang’s sentencing—Wong pulls Reed out of his head, out of his clear-cut thinking.

Simultaneously, these outings and others force Reed into the world, where he must interact with real people, not the archetypes he has constructed from his teach-in readings. The divide is not as simple as “Asians focused on their small businesses, totally ignorant of the racial context that allows them to succeed” versus a “Black community in a position of captivity.” It is in these tense scenes that Wong’s characters embody the “undefinable, unpredictable” nature of humanity that Baldwin wants us to acknowledge—their behavior and actions are not just the result of their categorization and politics, but a slew of idiosyncratic pushes and pulls, historical and personal. Wong stretches Reed through these smaller ideological wrestling matches to lay the groundwork for his climactic moment of reckoning with the movement.

Discomfort can breed further entrenchment in your own positions, but it can also drive self-interrogation. Wong could have written a pure satire of the puritanical strain of leftist Twitter politics, where people are all too eager to pile on others for problematic missteps, with Reed descending into his script of talking points, of “improving mottoes.” Instead, Which Side Are You On charts how the real work of activism comes not from merely announcing what you stand for and against, but from empathy grounded in understanding how much you still have to learn.