As if Donald Trump’s big-league lead in the polls wasn’t enough of a reason to stop paying attention to Iowa and its first-in-the-nation caucus now, anyone unfortunate enough to still be paying attention was treated to this week’s undercard debate between Nikki Haley and Ron DeSantis. The sniping, stammering, and eye-rolling was all kids’ table stuff, without even the whinging smarm of Vivek Ramaswamy as Ted Cruz’s tech-bro younger brother.

But there is no “adults’ table” in the modern GOP. It’s chaos and pouting, all the time. Trump staged a town hall on Fox News to run opposite the debate intentionally but anyone who took the time to compare the two events would have been at a loss to determine who was “unpresidential” and who was “presidential.” The choice was just between obviously and not-so-obviously unhinged.

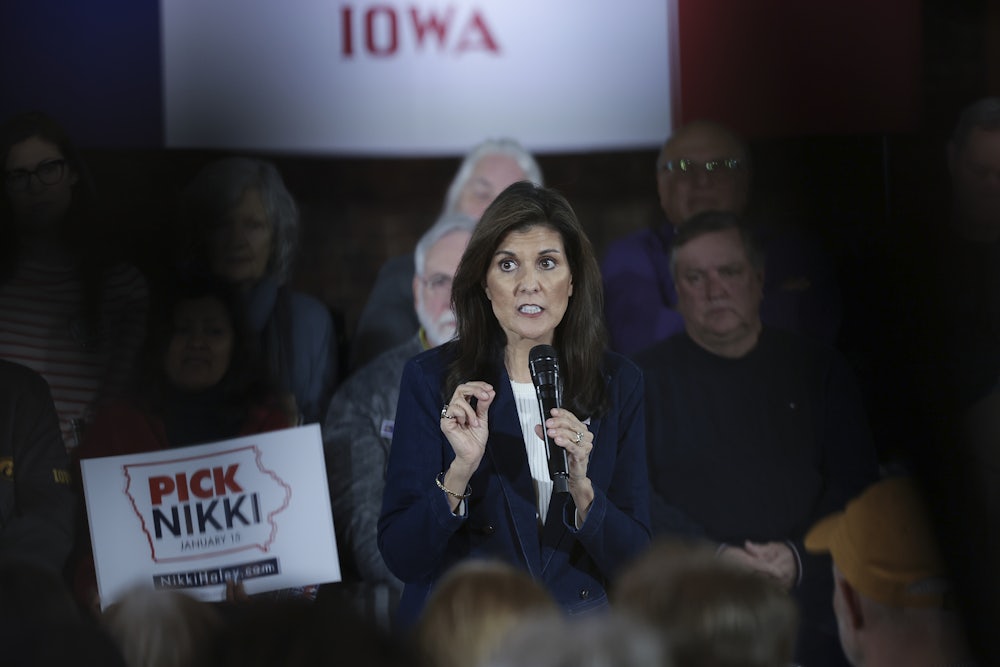

But I drove around Iowa for many days recently, and the conventional wisdom about the 2024 Republican field is wrong. Trump is not inevitable. And Nikki Haley is the most dangerous candidate the GOP has produced in a decade. She is also the most capable of beating Joe Biden.

Iowans greet reporters covering the caucuses with the wary Midwestern friendliness that, in Minnesota, they call “neighborly right up until the front door.” Over the years, I’ve found potential caucusgoers happy to discuss their political thinking but often reluctant to forthrightly declare their allegiances. Those not familiar with the culture of the caucuses—or who harbor stereotypes of simplistic rural conservatism—might be surprised by the Sunday morning talk show–ready punditry exhibited by men with farming-brand gimme caps and women with multiple pieces of cross-adorned jewelry, who can hold forth on electability and strategy with the best of talking heads. Unlike most cable newsers, they tend to refer to the challengers by their first names—an artifact of having the hopefuls tromp through living rooms and county halls so regularly. “I think if you look at Ron’s record in Florida, he’s got the appeal to get the Trump votes,” one gentleman told me. Another: “Nikki can get the suburban women Trump can’t.” (Not sure if it’s reverence that keeps Trump from being “Donald” or just the sense that “Trump”—that plosive “p”!—has always suited him better than his first name.)

Their caution is due to more than charming prairie stoicism. Politically active Iowans of both parties are historically protective of their position as First in the Nation and enjoy playing out the suspense of what will go down on caucus night. With the disastrously glitchy accounting of 2016 having scared the Democrats into rethinking Iowa’s sacred position in their selection process, Republican voters seem to be playing their cards even closer to the vest and squeezing out any drama they can from what appears to outsiders like a contest so sloppily one-sided it’s barely worth monitoring: After all, Trump has a 49-point lead over his nearest competitors’ polling averages; 53 points in the latest YouGov Poll.

But speaking to actual Iowa caucusgoers reminds you of a variable unique to the Hawkeye State: Iowans are cagey about their votes because they are really, truly not sure what they will do.

The caucus format encourages not just last-minute decisions but after-the-last-minute conversions: Neighbors gather in public spaces to listen to each other make speeches on behalf of their nominee, and the appeals are not necessarily tethered to policy or even an official campaign statement. The system combines the worst aspects of an election to the high school homecoming court with the dark-money machinations of American national politics. It is more like homecoming, actually, because many of the caucuses occur in the same places as high school dances.

You can be charmed by the process’s lack of professionalism even as you are appalled by how fundamentally undemocratic it is. At a caucus in 2020, a volunteer handed me a fun-size candy bar stapled to a flyer: “MOUNDS of support 4 Warren!”

Yet it is the wild, hyperlocal horse-trading, unpredictable circumstances, and literal sugar high of the caucuses that could defeat the Republican candidate least interested in democracy—or at least the one most vocal about his disinterest. Though much of the national media has been more focused on the various court cases threatening to keep Trump from participating in the 2024 election, he could still be sidelined the old-fashioned way: Not enough people vote for him.

At least, that’s how it’s supposed to work this year. The Democrats have done away with some of the truly batty caucus procedures—for the first time, there will be secret ballots! And they won’t make people physically gather into cliques representing candidate support. But the caucuses are still misshapen beasts, prone to unpredictable behavior: They are a multihour commitment in the dead of winter, in which neighbors try to convince neighbors to swap their vote.

Let’s recall the absurdities that emerge from the caucuses. Since 2004, there have been seven contests in Iowa: Democrats in 2004, 2008, 2016, and 2020; Republicans also in 2008 and 2016 and on their own in 2012. In every case, the final results looked vastly different than the polling suggested—either because of an upset or a landslide emerging out of a tangled polling clump. You might recall the biggest shocks: Obama leaping from a dead heat with Clinton to win by seven. Santorum surprising himself by going up eight points to beat Romney. Cruz going from four points behind to four points ahead of Trump—and little Marco coming in second!

But even when the results match expectations, a close read of the results tells the story of a process and a populace that confounds expectations more than it meets them. In 2004, John Kerry, Howard Dean, John Edwards, and Dick Gephardt started the morning of the caucuses in a statistical dead heat; by the end of the night, Kerry had collected 13 more points, Edwards 11, with Dean falling by a few and Gephardt by seven.

This year’s particular variables are familiar but threaten to destabilize the rickety framework of the caucuses: A wave of bitter cold and winter storms is currently sweeping the state. These have interrupted campaigning already; forecasts in Iowa’s three population centers are at least three or four degrees below zero. In some of the more rural counties—which, OK, means most of Iowa—the forecast goes as low as negative 14. These will be the coldest caucuses ever.

The massive lead Trump has is its own burden. Even a man as eager to believe in his own popularity as Trump has managed to grok that his apparent inevitability could break him. To turn his supporters out, Trump must insist he could lose, though it wounds him to say so. “Pretend you’re one point down,” he urged them this week. He has also said the situation is dire enough that he might caucus for himself—“We’d love to have you fill out the card; I’ll caucus with you”—so much for caring about voter fraud.

A close examination of the polls reveals another vein of instability in Trump’s lead: An unusual number of Iowans have admitted they are undecided or might switch their support; a late-December Fox Business poll found that a full third of respondents said they could change their minds. For comparison sake, 2016 polls showed that 86 percent of respondents were either completely decided or “strongly committed.”

Only 16 percent of Trump voters express uncertainty; around 40 percent of Haley and DeSantis supporters confess such squishiness.

But given the mutable alliances of caucus night, dropped support for DeSantis or Haley doesn’t necessarily work to Trump’s benefit. At this point, anyone supporting his rivals is doing so as an explicit rebuke of Trump as the nominee, if not Trump himself. I talked to several voters who voted for Trump twice and appreciated his presidency. Over and over, they echoed what Haley and DeSantis have said from the stump: Either he’s a distraction, or he’s distracted, or both. The question Trump skeptics will ask themselves on caucus night is probably not, “Can I live without Trump at the top of the ticket?” but, “Who do I think can beat Biden?”

I don’t think it’s Ron DeSantis.

I would prefer people decide who to support based on their position on issues and not their electability. I also think DeSantis is a disingenuous hate goblin with an ideology born of utter convenience. So it gives me no pleasure to report that the DeSantis supporters that turned out for his events are picking their candidate based on his positions. His Trumpy positions.

I hate to make fun of people for their looks or just way of being, but, again, speaking as an outsider, DeSantis moves through the world with oblivious awkwardness. He has the affect of an animatronic bear. Maybe that’s why he hates Disney so much. A lot has been made of the evidence that he wears lifts to appear taller, but I don’t think we should shame people for dressing in a way that supports their gender identity.

But none of the people supporting him care much about the strangeness of his smile or weird way of standing. They cheer him because he has more finely tuned his speech to the dog whistles that excite the Trumpist base. He’s big on “woke mind virus”–style fearmongering. Disney is “trans-ing kids”; there’s porn in the schools! Also, he shipped a bunch of “illegals” to Martha’s Vineyard. All of this hits exactly where it is expected among his fans. But listening to him as a visitor from planet general election, he can sound like he’s running a very obscure RPG. There’s some mystical power called “DEI”? A villain named “Soros”? DeSantis vowing to be “the worst nightmare for the medical biosecurity machine” sounds like he’s playing something from the Alien franchise, not running for president.

I’m not sure he believes what he’s saying, but one lesson he’s taken from Trump is that you don’t have to believe in anything as long as you’re willing to go to war against vulnerable people. DeSantis has all of Trump’s nihilism—but is even less honest about it. He presents himself as a moral crusader. He’s less interested in morality than power. Elected by a thin margin in 2018, his first year as Florida governor—including his initial reaction to Covid—showed him to be center-rightish and willing to work with Democrats. Then he started his working on his résumé for the presidential campaign.

The media continually misreads his “decisive” Florida victory in 2022; he won by a lot because he cheated a lot, instituting various hurdles to voting that suppressed turnout among likely Democratic voters and eased access in GOP strongholds. It didn’t help that the Democrats were running a re-retreaded Charlie Crist—well dressed but grey all over; a human gym sock.

Watching DeSantis is depressing. He is Trump minus the indictment and a few inches up and around. I sometimes wonder if he’s jealous of Trump’s mug shot. The only good news about DeSantis is that if he finishes third (as current polling indicates), he will also have no money left. As the saying goes, there are only two tickets out of Iowa—up or out.

The bad news about DeSantis is that Haley is a surging second in New Hampshire and she is worse news for Democrats, and maybe America, than him.

Haley could beat Biden. The polls already tell us so; in the latest round from The Wall Street Journal, she bests the president by 17 while Trump and DeSantis squeak by, almost within the margin of error, by four points.

She is a frighteningly talented campaigner in person. Like most politicians on the stump, she sticks to a set speech at every event. What makes her special is how she manages to illuminate it with conviction. She possesses an improvisatory spark, sure-footedly swerving off topic with a wink and nod, as if to admit, “See, we all know I’m giving a speech, but I’m also here with you, listening to myself give a speech.”

After an audience member sneezed at one event, she interrupted her patter with a “Bless you” that telegraphed empathy and conviction: “I can care about you and still take care of business.” I was impressed; I was even more impressed when the exact same thing happened four hours later at a different campaign event. I can’t say if the sneezers were planted—at this point in the campaign season, it’s a little late for allergies—but more power to her if they were. If Haley is going to win Iowa—or even come in a strong second—it will be primarily because she and her team have put that level of detail work into making every spontaneous (or was it????) audience sneeze worth something.

Such moments demonstrate the strengths of Haley’s superficially traditional campaign. With a little extra shove against the weight of disbelief, her events allow one to imagine that the past eight years have been free of Trump’s reality-warping presence. She doesn’t mine Fox for easy outrage material, and I don’t think I’ve heard her say “woke” once. She speaks passionately but without venom; it’s not that she doesn’t call for bloodshed; she just directs her fire against targets invoked by politicians of all stripes (look out Hamas, terrorists, and cartel members). This passive-voice violence may not be as satisfying as Trump going full Nazi (immigrants “poisoning the blood of our nation” and all); 50 percent of Iowa Republicans say they like Trump more now! But does liking him translate to believing he can win?

Every aspect of Haley’s campaign sets her apart from Trump and DeSantis. Suppose you didn’t listen to what her actual policies were. You might come away believing that she was set to personally repair every behavioral norm broken over Trump’s fleshy thigh during the past eight years. This is what she wants event attendees to hear, and it is what the people I talked to heard. The Iowans focused on the general are turning out for Haley, which should terrify us all.

Watching her work the rooms during the day I spent with her in Iowa, I understood how her dark-horse run for governor slingshotted her from backbench legislator to “face of the New South.” At the time, you may recall, the Republican Party was rebranding as a haven for “mama grizzlies,” Haley was shoehorned in among more flashy personalities such as Sarah Palin and Christine O’Donnell. Her style was always too soft-spoken to fit comfortably into the Tea Party patois of the time. But unlike most of that crowd, she never faded from view. It’s a testament to her skills as an administrator and her devotion to the conservative policy that that she stayed in the front ranks of the party even as Palin and O’Donnell have shuffled off into shabby notoriety.

But her political agenda was never significantly different from that of the far far right, and it still isn’t. DeSantis has tried to frame her as insufficiently devoted to terrorizing trans people, pregnant people, and immigrants. And it’s true that she doesn’t sound like someone reposting Libs of TikTok memes.

However, the difference between howling about “trans-ing kids” and calling “boys in girls’ sports the women’s issue of our time,” as Haley puts it, is entirely semantic. Both of these phrases betray a bedrock belief that trans people should not exist. She says we shouldn’t call undocumented immigrants “criminals,” but, just like Trump and DeSantis, does want to deport all 11 million of them that now call the United States home. I’ve written about her insincere mewling for “compassion” regarding the “abortion debate” before. My own view is that she can fuck off with her compassion; we need abortions. But The New York Times and Ron DeSantis have confused her honey-glazed rhetoric with moderation. In so doing, they make her general election argument for her.

Her foreign policy positions resemble something that neocons and neoliberals would recognize. Does that make her a “moderate”? More to the point, are her foreign policy positions the thing that will make or break her in Iowa? She’s gotten to second place without backing away from them.

As Trump and DeSantis frame it, Haley’s sin is that she is a reminder of what normal politics looks like. But the fact that she is only a reminder and not literally poised to part from the nihilist policy brutalism of the modern GOP is her strength. She’s a Trumpian wolf clad in sheep’s vibes, and she’s pulling the wool over the eyes of all the right people.

In this week’s debate, DeSantis squawked about the trending topics that fire the sick imaginations of the stochastic terrorists swarming over X, a.k.a. Twitter. At the same time, Haley talked like a politician, rattling his mechanics with repeated references to his campaign’s weeks-long fall into chaos. She reminded the audience that his super PAC has put $150 million into the race and just gotten lower and lower poll numbers. The hate-seeking bear opened his mouth to respond and closed it without speaking; are the animatronics finally breaking down?

I’ve been covering Iowa for two decades now. It has always been long drives in straight lines followed by Caesar salads in chain hotels. Despite the reliable rhythm of it all, the caucuses have constantly surprised everyone, including me.

Iowa looks flat, but it is sharp. There’s no caucus result that should comfort people who care about continuing to correct this country’s curve into despotism. The best-case scenario is that DeSantis’s enormous investment pays off (and he truly has sunk the ducats into this effort; I went to a postdebate buffet, and there were petit fours and specialty meats!). That way, we end up with months of Donald and Ron—two squabbling man-bear-pigs turning off general election voters over and over again.

The status quo—Trump shuffles off with a huge win—is medium frightening but in a familiar way. If the matchup between Trump and Biden solidifies this early, Democratic complacency is the biggest enemy.

The worst-case scenario is that Haley’s sleek self-presentation and the unwitting collaboration of her opponents lift her into second place in Iowa and a win in New Hampshire (she is currently 46–50 in head-to-head polling against Trump). After that, well, the GOP gets a chance to decide if it is so dedicated to patriarchy and white supremacy it would rather lose the presidency than put a woman of color on the ticket. Perhaps not even as president; she has refused to say she wouldn’t be Trump’s V.P. If the Republican base is willing to shelve their prejudices just long enough to nominate her, they will get the regime of utter intolerance they want in the end.