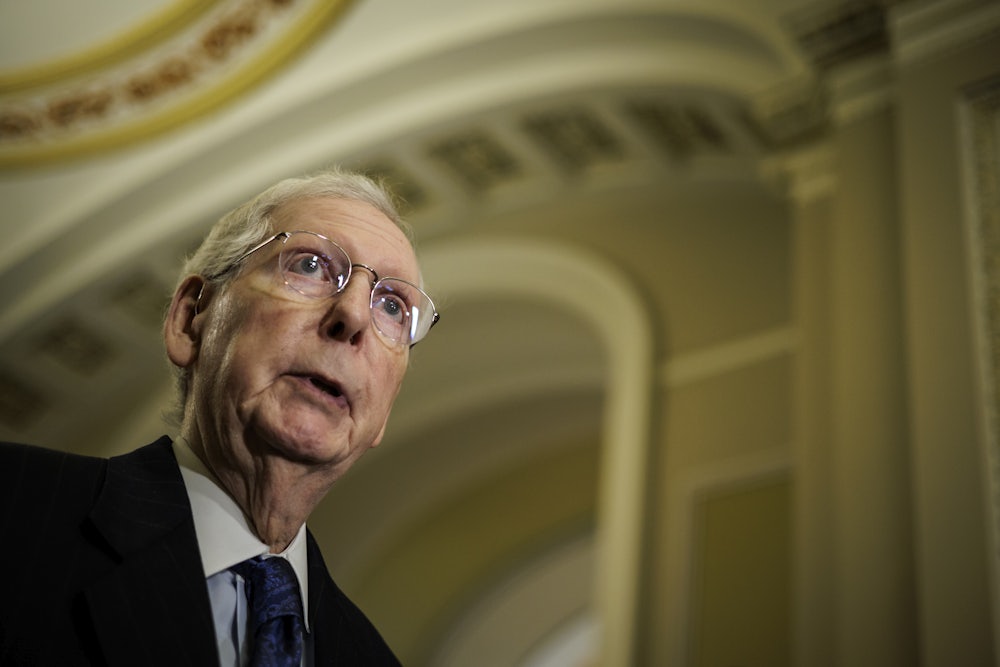

It’s almost an understatement to refer to Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell as a savvy political actor, who long ago cemented his position as one of the most consequential lawmakers this century. But as the nearly 82-year-old Kentucky lawmaker grapples with his legacy after two decades leading the GOP conference, he suddenly finds himself facing dueling and potentially incompatible priorities: a deep desire to provide continued assistance to Ukraine in its war against Russia and a commitment to electing more Republicans to the Senate.

While the Senate mulls what may be one of only a few bipartisan pieces of legislation considered this year, McConnell must balance his talent for politicking along Trumpian fault lines within the party.

On Sunday evening, Senate appropriators released the text of a $118 billion national security supplemental funding measure, including a long-awaited border security bill crafted by a bipartisan trio of senators. The border measure, the result of months of negotiations by Republican Senator James Lankford, Democratic Senator Chris Murphy, and independent Senator Kyrsten Sinema, received criticism from hard-right Republicans even before it was released—the charge led by former President Donald Trump.

The legislation is expected to receive a procedural vote in the Senate on Wednesday, but it’s all but certain that this will fail. As Punchbowl News first reported, McConnell recommended that Republican senators vote against the motion to proceed in a closed-door meeting with his conference—essentially, filibuster the legislation that a GOP lawmaker was instrumental in negotiating. This reflects one of McConnell’s most canny traits: Even as he leads his conference, he will follow their will.

After Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said on Sunday that he had “never worked more closely with Leader McConnell on any piece of legislation as we did on this,” McConnell’s detractors pounced. Senator Mike Lee, a frequent thorn in the side of Republican leadership said in a social media post on Sunday night that “WE NEED NEW LEADERSHIP—NOW.” When I asked on Monday what the next steps would be for instating a new leader, Lee responded: “We’ll see.”

The context has changed somewhat here, at the start of this new decade—likely the last of his career. Although McConnell handily defeated an effort to install Senator Rick Scott as leader of the Senate GOP conference early last year, the challenge was interpreted by McConnell skeptics as a sign of discontent with his leadership. Scott told me on Monday that he still believed the party needed new leadership. “Many of us want to have something that would force Biden to stop being lawless and actually secure the border, and McConnell made the decision not to include that in there,” Scott said.

There is also already a very quiet, yet undeniably real, shadow campaign to eventually replace McConnell as the top Republican in the Senate. The octogenarian is next up for reelection in 2026 and would likely enjoy another pass as the majority leader before making a decision to run again.

As one of the most prominent supporters of Ukraine in the Senate, McConnell has been urging his fellow lawmakers for months to approve additional military aid to the country. In typical fashion, he has often framed his support for Ukraine in pragmatic terms, casting American aid as the best way to counter Russian aggression.

“I’ve never been under any delusion about why America was backing Ukraine’s fight. This has never been about charity. It’s not about virtue signaling or abstract principles of international relations. This is about cold, hard, American interests,” McConnell said in a speech on the Senate floor in late January. “We cannot pretend that America is inoculated against the consequences of war in Europe. We can’t afford to harbor the notion that leaving Russian aggression unchecked would somehow enhance America’s posture in strategic competition with China.”

That pragmatism is on display with his approach to leadership as well. McConnell has an “unsentimental read on where the conference is at all times,” a Republican strategist said. “His job is safe precisely because he anticipated how this is playing out, and will proceed accordingly,” the strategist continued.

While support for Ukraine among Republicans has been waning in the House at a much faster rate than in the Senate, McConnell’s charges in the upper chamber have become increasingly vocal in their concerns about sending the country more aid. To make the deal more palatable to Ukraine skeptics, the supplemental funding package became entwined with bipartisan negotiations to overhaul the nation’s policies at the southern border.

But the plan to sweeten the deal only turned sour, thanks to a figure well known for his yen for disruption: Trump. The former president, along with House Republicans led by Speaker Mike Johnson, has become increasingly outspoken in his opposition to the bipartisan border legislation. McConnell is hardly a fan of Trump, but he recognizes the former president’s influence among the party’s voters and key lawmakers—particularly given his status as likely 2024 Republican presidential nominee.

“For most Republican voters, Donald Trump would probably be the most credible person on immigration that they could think of. So you cannot downplay the significance of his attitude on this,” said Jennings.

House Republican leadership has already uniformly expressed its opposition to the legislation crafted by Lankford, Sinema, and Murphy, as well as the larger supplemental. Johnson said that the bill was “dead on arrival,” and Majority Whip Steve Scalise—who sets the House floor schedule—said that the measure would not receive a vote in the lower chamber.

“Any consideration of this Senate bill in its current form is a waste of time. It is DEAD on arrival in the House. We encourage the U.S. Senate to reject it,” House Republican leadership said in a joint statement on Monday. Meanwhile, Trump said in a post on Truth Social Monday, “Only a fool, or a Radical Left Democrat, would vote for this horrendous Border Bill.”

Whatever his own personal priorities, McConnell must also wrangle the individual wants of his Republican members. GOP Senator Kevin Cramer described McConnell’s job—and his talent—as “reading the room.” He understands where his conference is, Cramer said, and balances “persuading where you can, and listening where you can’t.”

“His voice isn’t as loud as it used to be. I think that’s by his choice, but I think it’s also reflective of the situation right now, that there are some people that feel just a little bit more strongly about this issue,” Cramer told me last week. As Senator Bill Cassidy, another Republican, described McConnell’s current role: “I think he’s allowing the conference to work his will, and that’s what leaders should do.”

Senator J.D. Vance, a McConnell skeptic, told me on Monday that he believed McConnell should now withdraw support for the legislation. “I think the proper role of leadership, now that we’ve seen the text and seen how bad it is, is just to actually pull the plug on this thing and get us out of the situation,” Vance said.

It’s unclear whether the border legislation can even pass the Senate, much less the more conservative House—particularly if the procedural vote fails on Wednesday. This could result in a decoupling of that bill with aid to Ukraine, Israel, and the Indo-Pacific region, despite the months of talks that brought lawmakers to this point. Although McConnell has maintained his support of the potential package tying border policy to supplemental funding, it may not be politically feasible. McConnell recently acknowledged in a closed-door meeting with Republican senators that passing such a bill would be politically difficult, particularly given Trump’s vocal disapproval.

“I still favor trying to make a law when you can. And I do think that what Senator Lankford and his team are going to produce is an improvement over current law,” McConnell told reporters last week.

The Republican strategist, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to talk candidly, argued that “calling an audible and figuring out another way is prudent.” “Even if we think the odds of the Ukraine funding passing are lower than they ever were, at least they have a chance,” said the strategist. “It’s much easier to resolve it if you isolate the problem to just Ukraine and take away the toxic politics of immigration, and what a weapon it is to the people who want to kill it.”

McConnell and Senate Republicans have thus far largely allowed their GOP counterparts in the House, who hold a narrow majority, to set the party’s congressional agenda. But this strategy is complicated by a largely dysfunctional Republican conference in the House, riddled with divisions and apparently content to float from funding crisis to leadership crisis, over and over again for the foreseeable future.

The deference to House Republicans is certainly reflective of the fact that the GOP is in the majority in the lower chamber and not in the upper house of Congress, but it is also part and parcel with a growing ideological shift within the Senate. The House tends to be more attuned to the party base, but GOP senators, rather than embracing their recent role as temperers of lower-chamber right-wing excess, are lately much more inclined to follow suit. Moreover, it has become politically toxic among a portion of the Republican electorate to cut any kind of compromise with Democrats—no matter what concessions might get extracted from doing so—further complicating the passage of border legislation and, by extension, aid to Ukraine. That sentiment is only exacerbated by Trump’s barrage of social media posts opposing the deal.

“To the extent that the votes in the Senate are increasingly contingent on where the votes are in the House, that makes this job especially tricky,” said the Republican strategist. “Some of that is a reflection of where the party is, and the conference is looking more like the party than it perhaps has in recent Congresses—more populist, less international, certainly more nationalist.”

In theory, it might be better for Republicans politically to keep the border as a campaign issue; this appears to be the route preferred by Trump, who has vociferously opposed the as-yet-unreleased proposal. This could help Republican candidates facing off against vulnerable Democratic incumbents in red and purple states such as Montana, Ohio, Nevada, and Pennsylvania. (For his part, Senator Steve Daines—the chair of the campaign committee dedicated to electing more Republicans to the Senate—said on Sunday that he “can’t support a bill that doesn’t secure the border, provides taxpayer funded lawyers to illegal immigrants and gives billions to radical open borders groups.”)

However, disavowing border legislation tied to Ukraine funding could also be politically dangerous for McConnell and Senate Republican candidates. “The other way to look at it is, what if you had the chance to do something and you turn your back on it? I mean, do you think voters might punish you for failure to govern?” said Jennings. “It sort of cuts the knees out of what we’ve said, which is it’s an invasion, and it’s a humanitarian crisis, and it’s Joe Biden’s fault. But don’t worry, we can put it off for a year, depending on the outcome of a presidential election we may or may not win.”

When I asked Cramer whether McConnell would choose electing more Republicans over passing a bill addressing the border and Ukraine, the North Dakotan highlighted McConnell’s famed pragmatism.

“Mitch is a political animal. He understands the long game, and the long game is that we can do more with a majority than we can with the minority,” Cramer said, citing the name of McConnell’s 2016 memoir, The Long Game. “I don’t think he would take a momentary victory over a longer-term governing majority, especially considering that this may be certainly the easiest time in recent history and going forward for us to regain the majority.”