Have you been to the Trump Ocean Resort Baja Mexico? It’s absolutely lovely; you must visit one of these days. I did, a little while back. Let me tell you all about it. The resort is in Mexico, just over the border with the United States and southwest of “TJ,” as Tijuana is generally known to locals from both nations. My visit took place during a family trip through Baja. I had to go, to see what golden glories Donald Trump had foisted on this nation of supposed “bad hombres.”

It was bad, hombre. Trump Ocean Resort Baja Mexico cannot, it is my unfortunate duty to report, be called one of the more luxurious hideaways in the vicinity of the Punta Bandera wastewater treatment plant. What it can be called is a huge, muddy hole with glorious views of the Pacific, only no bungalows or hotel rooms or even beach chairs from which those views could be enjoyed. There was a chain-link fence, an empty guard booth, and nothing else. I lingered for a few moments, while the rest of my family waited in the rental car. I don’t know if my wife explained to the children; I don’t know if there was much to explain. Daddy was chasing after Trump’s wealth, and chasing after Trump’s wealth sometimes took you to unusual places. At least I didn’t drag them to Azerbaijan.

Trump Baja is a classic Trumpian swindle: grandiose promises that shatter like cheap glass against the hard, unyielding edges of reality. For a man who became famous for his forays into the brick-and-mortar business of real estate, Trump has thrived and survived by jumping from one lily pad of fantasy to another, saved at critical moments during his career by bankruptcies and loans, not to mention ordinary Americans willing to hand him their money and their trust.

But as Trump runs for president for the third straight time, his political and business fortunes are headed for an unpredictable collision. His decades of making grifting look like business acumen could be coming to an end, thanks to a number of civil and criminal cases that could not only extract hundreds of millions of dollars from him but hinder him from campaigning—and possibly even put him in prison.

“Trump’s career has been to go from business fraud to election fraud,” said Norman L. Eisen, who advised the House Judiciary Committee on the first Trump impeachment and remains a strong critic of the former president. “The bill is finally coming due. It’s starting to be paid.”

Then again, Trump is not exactly known for paying his bills. And this time around, the whole nation could be on the losing end. The cases brought against him by special counsel Jack Smith (one for whisking classified documents away to Mar-a-Lago, the other for his role in instigating the January 6, 2021, insurrection) are devastating. Or should be, at any rate, except Trump’s attorneys have successfully delayed both (having a Trump-appointed judge helps). Then there’s an election interference case in Fulton County, Georgia, where District Attorney Fani Willis has Trump dead to rights committing fraud. Only her ill-advised decision to hire an attorney with whom she was having a romantic relationship to work on the Trump case turned into a disaster of its own, not to mention a media circus. So now that case is in limbo, too.

The delay-delay-delay-and-then-delay-some-more approach “was their absolute best play. And they worked it to almost complete perfection,” said Bradley P. Moss, a Washington, D.C., attorney and a frequent Trump critic. Almost, but not entirely: In late May, Trump became a convicted felon when a Manhattan jury found him guilty in the Stormy Daniels hush money case. (Trump’s campaign did not respond to a request for comment from The New Republic.)

Over the years, I have come to think of Trump as an autoimmune disease, very much a product of our own body politic. And as is the case with such afflictions, he is curiously resistant to ordinary treatments. In fact, they only make him stronger. Which is to say that Trump could emerge in October having been found not guilty in at least one trial, and with the rest receding into the distance, shackled by motions and countermotions.

He would be vindicated and vindictive, ready to use the federal government to punish his enemies. Beyond going after obvious adversaries like U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland and Hunter Biden, the current president’s troubled son, he will stock his administration with effective ideologues who will use his grievances to remake every aspect of American life, eliminating social services, rolling back green policies, restricting abortion, and promulgating Christian nationalism wherever they can.

Un-Invincible

Trump is rich. Very, very rich. Unimaginable wealth whose scope would require a whole new branch of mathematics to describe is the foundational premise of the Trump myth, the unstated but universally understood creed at the heart of MAGA. He demands to be understood through the prism of immense wealth. “I’m really rich,” he explained in his 2015 announcement speech, vowing not to rely on donors and lobbyists (which he soon enough would).

His career has been full of such promises, lies blithely tossed out like coins to paupers. “When I worked with Trump, he was a P.T. Barnum,” said Barbara Res, who was a high-level executive at the Trump Organization into the 1990s. He even lied about the number of floors at Trump Tower. “Trump is a fraud. He is a cheat. He is a thief. He is a criminal,” Res said of her former boss. I doubt he still sends her Christmas cards.

Lately, Trump’s record of dishonesty in both business and politics has come under a scrutiny that not even John Barron, Trump’s fictional alter-ego press agent, could negate with a well-placed item in the New York Post.

“We’ve always said, if you want to understand Donald Trump—we’ve said this from the very beginning—just understand the money,” MSNBC host Joe Scarborough commented last year. Not just where he got it, which is always a question with him, but also how. And what he did with it. And what he offered in return.

“It’s all bullshit,” Res said of the eternal hype man. But things have changed, she added. “He exaggerated to a fault, but back when I knew him, he was not really scamming,” she wrote in an email. “Now, yes.”

The business ventures, the political campaign … it is all a version of the Baja resort, a muddy hole promising ocean views. His detractors and opponents are giddy at the possibility that he will spend his remaining days in a resort of Trump Baja–like amenities, with a Department of Correction sign on its gate.

They’ve thought that many times before, only to be somehow bested by a man with the survival instincts of a cockroach. Trump’s career began with the destruction of the Bonwit Teller department store on Fifth Avenue, his promises to preserve the graceful art adorning its facade quickly turning out to be little more than false assurance. And here he is, more than 40 years later, striking licensing deals in Dubai. If that is not genius, then Garfield is not a cat.

Garfield is not a cat—he is a cartoon character, created by Jim Davis. Donald Trump is a cartoon character, too, a fictive businessman created by the tastemakers and gatekeepers who knew better but said nothing: the bankers and newspaper editors, the politicians and producers, all of whom sustained his legend in hopes of profiting from it.

Maybe it was January 6 that changed everything. Maybe the prospect of a second Trump term, and what it would mean for the American project, also made a difference. Whatever it was, Trump suddenly lost his invincibility, as both a businessman six times bankrupt and president twice impeached.

The Walls Start to Close In

Since the beginning of the year, Trump has been battered by a series of court cases that threaten to reveal just how little cash he has—and to take a good chunk of what he does have, all while straining his third run for the White House by hijacking his fundraising operation to pay his legal bills. Florida federal Judge Aileen Cannon and the conservative justices on the Supreme Court are obviously trying to save him (without imperiling their own reputations, presumably), and the delays in some of the criminal cases mean that he may reach the legal sanctuary that is the Oval Office before federal prosecutors get the chance to try him. But he won’t pull through unscathed.

“He’s finally met a mechanism he can’t control,” said Moss. “And it’s the criminal justice system. It’s not like it’s Robert Mueller, where he could just threaten to fire him or he could obstruct the investigation. He is not in control.”

The year began with Trump ordered, in late January, by a federal judge to pay $83.3 million to E. Jean Carroll, a fashion writer who accused him in a civil trial of raping her sometime in the 1990s in a dressing room of the Bergdorf Goodman department store. In early March, Trump posted a $91.6 million bond and appealed the ruling in a bid to avoid payment. That bid failed, and late in April a judge refused to grant him a new trial.

Shortly after the Carroll judgment, he lost a case brought by Letitia James, the New York state attorney general, who accused him of consistently churning out false real estate valuations. That judgment, also in a civil trial, comes with a $454 million penalty. So far, Trump has had to pay only a $175 million bond.

Meanwhile, in a little-noticed but potentially disastrous development for Trump, a judge in Washington, D.C., has found that he could be held liable in three consolidated cases brought by House Democrats and law enforcement officers for injury incurred during the U.S. Capitol riot on January 6, 2021.

The politicized discourse surrounding the storming of the Capitol has occluded the human pain that day’s events caused. At least four law enforcement officers involved in the response committed suicide. Members of Congress and staffers who had to cower from the violent mob remain scarred.

“I haven’t felt that way in over 15 years, not since I was an Army Ranger,” Representative Jason Crow, Democrat of Colorado, said of his harrowing experience in the Capitol that day. In a social media message posted four days after the attack, he offered simple advice to others who had been through the insurrection: “don’t suppress post-traumatic feelings & fears. Seek help.”

Many have. But some want financial damages, too. “That strikes me as a potential huge judgment problem. How do you even put a number on somebody’s trauma from January 6?” wondered Robert DeNault, a Manhattan attorney who writes about Trump. “It could be a very unsympathetic jury,” he said, drawn as it will be from the citizens of a city Joe Biden won in 2020 with nearly 92 percent of the vote share.

While the judgments are likely to be much smaller than they were in Carroll’s case, the multiple cases will represent yet another drain on his finances at a time when he can hardly afford such encumbrances. And they will be in the headlines, potentially, for weeks on end.

Then there are the criminal cases: Besides the hush money case, which ended disastrously for Trump, there’s the one now languishing in Fulton County and two brought by Jack Smith, in South Florida (documents) and Washington (insurrection). Smith is a determined special federal counsel who has made no obvious unforced errors. Drawing Cannon, the Trump judge, in South Florida was bad luck, but the January 6 case in Washington could move forward this summer, depending on how the Supreme Court rules on the matter of presidential immunity.

“That would be a nightmare for Donald Trump,” Moss said, “because he would—unless he has authorization from the court—be stuck in court throughout the fall during the closing weeks and months of the campaign.”

Letitia James and Trump’s Bill Cosby Moment

Bill Cosby’s sexual predations had been known for close to a decade, yet there was something about the Cosby-themed jokes comedian Hannibal Buress delivered during a 2014 set that refocused attention on “America’s Dad.” It was inexplicable, a ripple in the zeitgeist turning into a tsunami that finally sent Cosby to prison in 2018. In some small part, it was because Buress simply said the thing that everyone seemed to know: that Cosby was a rapist.

Trump had a Cosby moment of his own in early 2024. He, too, might find himself in jail for transgressions that, like Cosby’s, have been well known for years. They just needed to be spelled out, made plain for all to see.

That is the role Letitia James had long imagined for herself.

A former state assemblywoman from Brooklyn, James launched her candidacy to become New York’s attorney general in 2018. By then, state attorneys general from California to Massachusetts had emerged as an effective bulwark against the Trump administration. After she won, becoming the first Black woman to hold statewide office in New York, James promised to join them in the resistance. “I will be shining a bright light into every dark corner of his real estate dealings, and every dealing, demanding truthfulness at every turn,” she said.

James was inaugurated on January 1, 2019. Late the following month, she took note as former Trump fixer Michael D. Cohen testified on Capitol Hill. Cohen, who had pleaded guilty to a host of financial and campaign improprieties in 2018, told lawmakers that Trump had blatantly exaggerated his wealth between 2011 and 2013 in order to gain favorable terms on loans from Deutsche Bank.

“It was my experience that Mr. Trump inflated his total assets when it served his purposes, such as trying to be listed among the wealthiest people in Forbes, and deflated his assets to reduce his real estate taxes,” Cohen said.

Less than two weeks after Cohen testified, James announced that she was launching an investigation into Trump’s finances, quickly moving to subpoena records from financial institutions, including Deutsche Bank, that had had dealings with him.

“Until Cohen blew the lid off, we did not know the scale,” said Tristan Snell, author of the book Taking Down Trump and a new newsletter of the same name. “It was one thing for him to lie about, like, the size of his condo tower. We didn’t realize exactly how he had been doing this systematically until Cohen gave us a sense of it. And then the AG started digging into it.”

Loan by loan, property by property, James’s office meticulously described the fundamental deception at the heart of Trump’s wealth, and the remarkably straightforward means he deployed to accrue that wealth. “It was not sophisticated,” Snell said. “This is not complex financial arbitrage.” Trump would tell Cohen and Allen Weisselberg, the former chief financial officer of the Trump Organization, that he wanted his personal worth to “go up,” and they would inflate accordingly.

There was a beautiful simplicity to the grift: 40 Wall Street, a tower in the heart of lower Manhattan, had been bought by Trump in 1995 for less than $8 million. By 2012, it was worth $527 million. Why? Because Trump said so. Trump Tower and Trump Park Avenue in Manhattan, Trump International Hotel and Tower in Las Vegas, and many other properties elsewhere all had fallen victim to fictive valuations. And it was those fictive valuations that allowed Trump to continue borrowing.

Trump’s liquidity had plummeted to a mere $192 million by 2015—and that was before Trump spent a reported $66 million of his own money on his first presidential campaign. He sustained his empire and image by borrowing against lies.

“The Donald Trump show is over,” James said outside the courtroom.

Judge Arthur F. Engoron ordered Trump to pay $350 million. Because of interest, the amount has since risen to $454 million. Trump has so far paid only a $175 million bond. The money was put up by Don Hankey, who made his own billions through predatory car loans. Snell thinks the bond is itself suspicious, because Hankey’s company, Knight Specialty Insurance, is only allowed to put up a $13.8 million bond, according to state rules. The bond Knight put up for Trump is, by Snell’s calculation, 1,260 percent higher than the permissible amount.

Snell also pointed out that, according to Letitia James’s investigation, Knight may have been using a Cayman Islands cutout to hide serious shortfalls in its books, further raising questions about the integrity of the bond. “This is classic Trump, I have to say,” Snell wrote. “Trump found the Trump of insurance.”

The Grift Intensifies

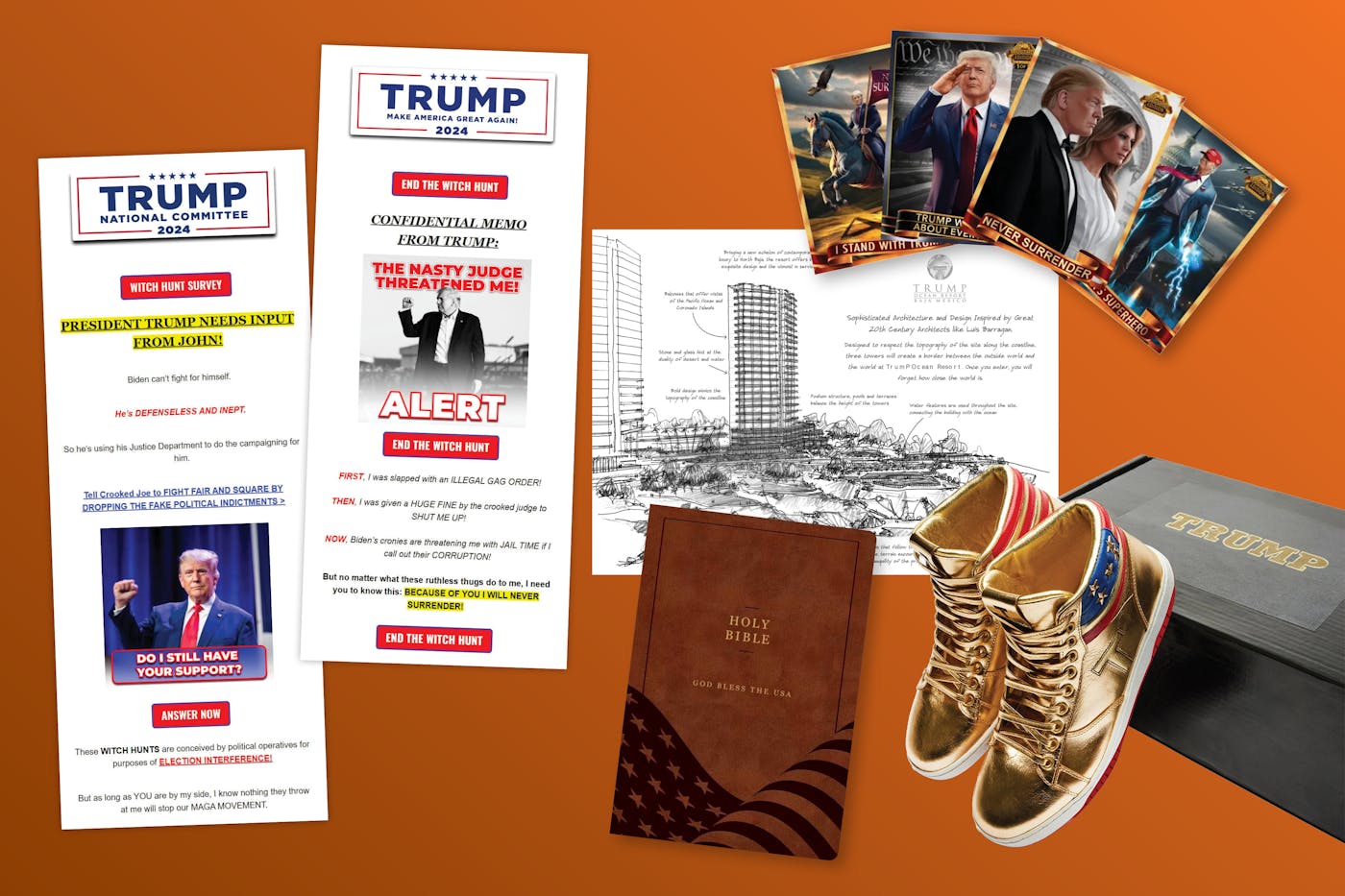

The Bible was priced at $59.99, more than double what you might pay for the Holy Book on Amazon. But this was an especially holy book, because it was the Lee Greenwood edition, hawked on the exceedingly patriotic country singer’s website.

Trump told his followers to pony up: “Happy Holy Week! Let’s Make America Pray Again,” the famously pious former president wrote in a social media post in March. “As we lead into Good Friday and Easter, I encourage you to get a copy of the God Bless The USA Bible.”

I did as instructed. After three weeks, the Greenwood Bible arrived, bound in what appeared to be faux leather, its pages gilt-edged. The word of God is what it is, but the production values were, I have to say, on the low end, leading to online speculation about whether the book was printed in China (probably, consensus says).

Before the Bible, there were Trump sneakers, which retailed for $399. The shoe, named “Never Surrender,” and possibly China-made, was introduced at Sneaker Con in Philadelphia earlier this year by Trump himself, who walked on stage to the sound of—wait for it—Greenwood’s “God Bless the USA.” He held up a pair of the shoes, which looked as if they had been dipped in a pool of gold. “There’s a lot of emotion in this room,” Trump said. He did not say what the emotion was.

Why is Trump hawking Bibles and sneakers?

Very simply, because he needs to. He needs money for the presidential race, because short of being Mel Gibson, returning to the White House may be the best get-out-of-jail free card in our political system. But first he has to get to Election Day, which requires him to pay millions of dollars to attorneys who have, so far, shown remarkable skill at delaying the most potentially damaging trials he faces.

It could be, then, that Trump manages to thread his way between clusterfuck and shit show, emerging in the late hours of November 5 as the forty-seventh president of the United States. But it’s going to cost him real money, not the fake stuff that Cohen and Weisselberg played with for years.

Trump began the year facing 91 felony counts across four separate jurisdictions. Each of those cases demands attorneys with knowledge of criminal and civil law, not to mention whatever kind of assistance those attorneys may require in the form of paralegals and other support staff.

Trump has a tendency to cycle through attorneys the way he once cycled through White House chiefs of staff, and it is therefore difficult to get a full picture of his legal team across different jurisdictions at any one time. “He’s got a bit of a hodgepodge of people from different firms,” said DeNault, the New York attorney.

Let’s give it a shot, though. Trump had three attorneys in the Stormy Daniels case; two in Fulton County; three for his election interference case in Washington. D. John Sauer argued the immunity issue before the Supreme Court. Todd Blanche was the point man in the Manhattan hush money case, joined by Susan Necheles, and is also handling the South Florida documents case. Blanche was formerly with Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft, a high-end Manhattan firm that was an industry leader in charging $1,000 per hour (other firms have caught up).

It’s impossible to say just what Trump is paying his lawyers today. But even if they are not charging Cadwalader rates, few are doing the work out of the goodness of their hearts.

“The fees must be out of control,” DeNault said. “I’m assuming most of these people have arranged some sort of financing agreement, given the reputation risk and his known reputation for not paying.” These are not the kinds of folks who are going to be duped by promises of Baja vistas, or villas in Oman. After all, they represent sophisticated swindlers for a living.

Political fundraising is notoriously obscure, especially in this age of dark money super PACs.

But earlier this year, The New York Times calculated that since 2021, when his career as president ended and his career as defendant was about to begin, “Mr. Trump has averaged more than $90,000 a day in legal-related costs for more than three years—none of it paid for with his own money.” The newspaper found that of the $104.2 million donated directly to various efforts to reelect him in 2023, $59.3 million—more than half—went to legal expenses.

“The small donors are paying for this,” Eisen said. It’s one thing to run a grift on people who can afford a $10 million condominium; quite another to bilk ordinary Americans who believe that MAGA is their way out of economic and social despair. Yet he keeps doing it—and they keep sending him their money.

Those donors “are getting fleeced by their fundraising strategies, which are pretty gross,” said Tim Miller, a former Republican strategist who now writes for The Bulwark and contributes commentary on MSNBC. “People are having the wool pulled over their eyes.” But others, he said, “are so deep in the cult that they’re happy to pay a proclaimed billionaire’s legal fees.”

Lately, Trump’s fundraising emails have taken on an especially unhinged quality. Trump is no longer simply asking for money. He’s begging for it. In early May, Juan Merchan, the judge in Trump’s hush money case, slapped him with a $9,000 fine for violating a gag order. Trump’s campaign quickly fired off what has become a typical solicitation. “The nasty judge just threatened me!” the subject line said. “But no matter what these ruthless thugs do to me, I need you to know this: BECAUSE OF YOU I WILL NEVER SURRENDER!” went the email.

“I am your retribution,” Trump famously tells his supporters. But not without your contribution, he may as well add. “These WITCH HUNTS are conceived by political operatives for purposes of ELECTION INTERFERENCE!” ` another fundraising email. “But as long as YOU are by my side, I know nothing they throw at me will stop our MAGA MOVEMENT.”

Laugh, but it seems to be working. In April, his campaign announced that it had raised $76 million. “Donald Trump is the master of this,” attorney Moss said. “There is no one who matches his ability to spin and refashion a negative into a positive. He gets that from the father,” Fred Trump, also a real estate developer of questionable ethics. “That’s what his father taught him: You’re always winning. You’re never, ever losing.” In the 24 hours after his conviction, his campaign claims, it raised nearly $53 million.

Earlier this year, daughter-in-law Lara Trump was installed as head of the Republican National Committee, as part of a purge that Politico described as a “bloodbath,” with some 60 staffers dismissed. The point, people who know the RNC’s internal workings say, is to ensure that as much cash as possible is funneled to Trump’s presidential campaign, as opposed to down-ballot races. The party apparatus was always going to stand behind its chosen candidate; now it just looks like it won’t stand behind anyone else.

Miller, The Bulwark’s editor, related the story of an RNC employee who, in early 2017, voiced concern about the Trumpian direction of the party on high-level conference calls. One day, while the staffer was at his desk, the phone rang. On the other end was Jared Kushner, the president’s immensely influential son-in-law, “kind of checking in, making sure he’s on board,” as Miller put it. “That’s just how the Trump family rolls.”

Fortune does seem to favor the shameless. In April, the RNC and the Trump campaign asked other candidates using his name, image, or likeness to donate 5 percent. “Any split that is higher than 5% will be seen favorably by the RNC and President Trump’s campaign,” the letter not-so-subtly advised.

The new Trump functionaries at the RNC are using the lie that Trump won the 2020 election as a loyalty test. As I understand it, any high-ranking official who says otherwise should be looking for another job. The committee’s counsel, Charlie Spies, was forced out of his job in early May because he had defended the integrity of the 2020 election in a 2021 speech.

If that’s not enough, this election cycle has seen $32 million spent by the Republican Party and Trump-affiliated committees at Trump properties. “Trump and his family are in the unique position to profit directly from his public service,” said nonprofit OpenSecrets, which chronicled the questionable spending. “Special interests in Washington have caught on.”

Another windfall may come later this summer, if Trump manages to sell his shares of Truth Social, the social media company founded by his associates. Truth Social went public in late March. Originally valued at $8 billion, the sparsely used platform has seen its share price tumble. Trump won’t be allowed to cash out until late September, but when he does, he could reap a windfall of more than $1 billion. “There are legal issues that pop up that throw that into doubt,” Snell said of the complex financial machinations that have turned a floundering social media company into a golden goose for Trump. “There could be an investigation.” True, but none has been announced so far, and the election is approaching.

Now or Never

In the fall, when Americans head to the polls to vote, the fate of Donald Trump and the fate of the American republic will converge in a way entirely new to American politics. “If Donald Trump wins in November, if he becomes president again, the two federal cases”—the classified documents and January 6 cases—“are gone. He will end them immediately on Day One,” said Moss, in reference to the charges brought against Trump by special counsel Smith. “He can order the whole thing shut down as president, and no one could stop it.”

Trump’s return to the Oval Office would make it impossible to actually prosecute him. That would have to wait until at least 2028, by which point phone calls made to Georgia election officials eight years before may not have the same legal potency they once did. That’s assuming he willingly leaves office in 2029, which is something short of guaranteed. It’s now or never.

“These next six months are all about him having a life outside of jail,” Moss said. Trump is fundraising as much to stay out of the federal penitentiary as he is to return to the Oval Office.

“The message about our system of criminal justice is an unhappy one,” Harvard Law School constitutional scholar Laurence H. Tribe wrote in an email. “Sadly, its elaborate safeguards, theoretically designed to minimize erroneous convictions, do much less for the innocent than they do for guilty. And when the alleged crimes are crimes against democracy itself, the old adage that justice delayed is justice denied casts an especially dark shadow.”

I invite you back to Trump’s resort in Baja California. The marketing materials for the project show modern glass towers set on the cliffside. “Mr. TRUMP is personally involved in everything that his name represents,” the attractive brochure says. Staring out over the barren ground beyond the chain-link fence, I could very much believe it.

The question is whether Trump will get away with one more grift. If not, he could find himself behind a fence, and a tall one at that, far from Baja California.