Pick your metaphor for the last eight years of American politics. Sewer or garbage truck? Practically every day a helpless nation watches a new scrap of official grift, crime, abuse of public trust revealed and tossed into the churning dumpster of history. Most of us identify this era with Donald Trump, who sailed down a golden escalator in the summer of 2015 and lit the dumpster fire. But in his bracing history of American conservative hustlers, The Longest Con, veteran political writer Joe Conason proposes that the American right has for more than a half century been increasingly OK with “politicized larceny.” After decades of professional fearmongers, scammers, and grifters chipped away at the line between right and wrong, the right was ready to support the idea, as Gordon Gekko put it, that greed is, actually, good. The ends always justify the means, if you can make bank on the way.

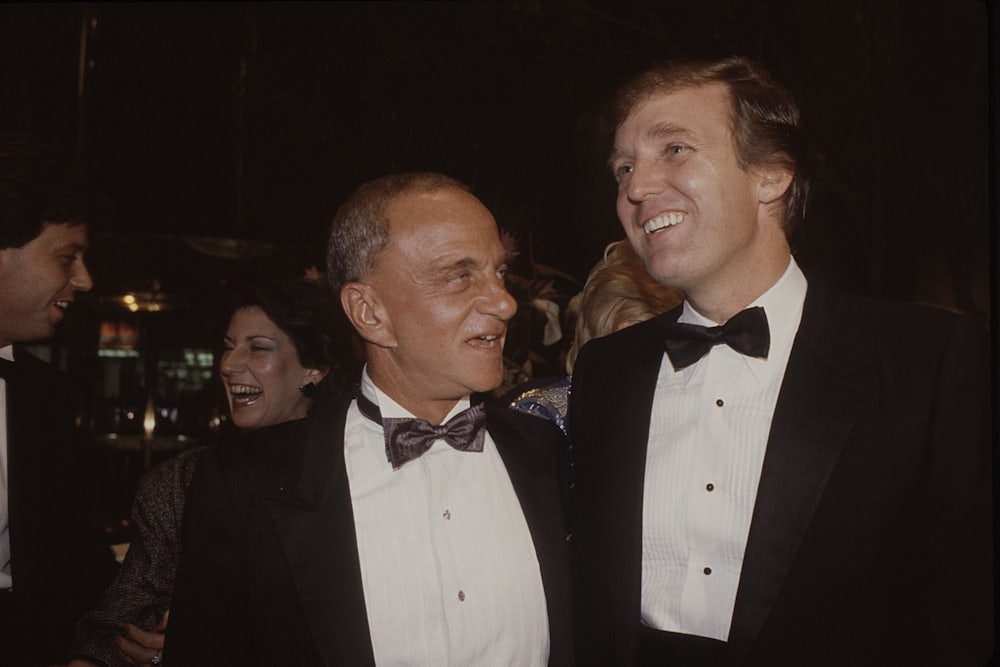

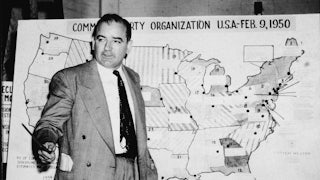

A crucial representative of this attitude, according to Conason, was Roy Cohn, the red-baiting Joe McCarthy aide, New York power broker, and Mafia lawyer whose “philosophy of impunity” was so successful that it shaped right-wing politics for decades to come. His most apt pupil was Donald Trump, whom he represented in his later years. Cohn taught the younger Donald that “it was not only possible but admirable to lie, cheat, swindle, fabricate, then deny, deny, deny—and get away with everything,” Conason writes. As a lawyer, Cohn’s motto was: Better to know the judge than to know the law. As a businessman, it was: Better to stiff creditors than pay bills; and always worthwhile to lie, bribe, steal, and swindle while never apologizing.

Conason devotes the first third of the book to some of the right-wing scammers “corroded to [the] core” like Cohn, who roamed the hinterlands of Cold War America preying on Red Scared hayseeds for personal profit. Unlike Cohn, many were nominal Christians, with names that sound like something straight out of Deliverance (Bundy, Smoot). They sold anti-Communism with Jesus. Oklahoman Billy James Hargis got rich off his radio ministry and as a fake doctor stumping churches and town halls of America on a “Christian Crusade.” He signed on former Army Major General Edwin A. Walker (a spiritual predecessor to General Mike Flynn), a man forced out of the military over John Birch Society propagandizing. Together the duo raked in money on a national tour warning auditoriums and town halls of an enemy within America’s schools, government, and churches who constituted a “repulsive Satanic force.”

The 1960s saw the rise of a new crop of operatives wielding modern technology. Richard Viguerie amassed a fortune and bought himself an estate in Virginia horse country by cornering the market on direct mail in the early computer age. His company reached its zenith after Watergate, when it was sending one hundred million pieces of mail annually, soliciting donations from gulls inflamed by keywords like “union bosses” and “federal bureaucrats” and “radical feminists” and “homosexual activists.”

Within the conservative movement, the audacity of con men appalled many, at least in the beginning. Paul Weyrich once said of Roger Stone’s penchant for Patek Philippe watches and bespoke suits paid for by his firm’s work for dictators that he “rivals Imelda Marcos.” (“Dictators are in the eye of the beholder,” Stone has said.) Stone, a Cohn acolyte, worked for Nixon (tattooing the disgraced President’s face on his back) and was still around to advise Trump. He understood that “Trump” as a brand, built on utter fakery, and Trump’s own penchant for schemes like Trump U, Cohnian lying, and impunity, made Trump a promising political candidate.

Conason devotes several chapters to the capture of the modern religious right by men and women who welded Christianity to massive moneymaking schemes. He explains how Jerry Falwell Sr. created Liberty “University,” which became a business model for tax-exempt Christo-capitalism—a model his son, Jerry Jr., would expand and then explode, but not before urging his flock to get in line behind a blasphemous, immoral scoundrel for president.

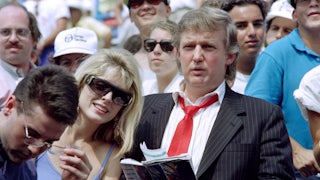

The arrival of the TV as remote church collection basket in every American living room inaugurated a new era for the prosperity gospel. The fake TV businessman who had fooled millions into thinking he was the second coming of Jack Welch was the secular version of televangelist grifter. “What drew the prosperity preachers and their congregations to Trump, eventually joined by millions of white evangelicals, was how much he resembled the televangelists who were the most successful among them,” Conason writes.

By the time Trump announced his run for president in the summer of 2015, the carpet was rolled out, table was set, and rank and file conservatives were primed. By election night 2016, many of the remaining shockable conservatives had already witnessed how depravity delighted and thrilled the political base. They had watched crowds chant along with calls for Hillary to be locked up and roar at Trump’s vulgarity. His supporters didn’t seem to care that he had ripped off thousands of people in his Trump U scam, failed to spend his foundation money on charitable causes, declared bankruptcy six times, or bragged about grabbing women by their genitals.

Refusing to accept the results of the 2020 election proved a particularly profitable scheme. In just two months between election day and the insurrection, the Trump machine raked in $255 million, “a record-setting haul by nearly any measure,” Conason writes. They accomplished this with a combination of the scams and strategies honed over the previous decades, augmented by technology: online ads and as many as 25 email appeals daily, appealing for money to fight a totally fictitious battle against a nonexistent problem. At least two million individual donations poured in. About eighty million dollars of that haul went to Trump’s Save America PAC, a pile “immediately available to Trump for his personal use to pay for travel and hotel costs” and later for his legal bills.

The current crop of MAGA scammers sprouts from the lineage of decades of conservative con artists. Steve Bannon was accused of taking millions of donor dollars for the wall between Mexico and the U.S. and enriching himself and others. Trump preemptively pardoned him on federal charges, but he still faces related state charges. The National Rifle Association, another conservative political organizing outfit, grifted itself into notoriety, tried and failed to go into bankruptcy, and was forced to defend itself against civil corruption charges.

The compendium of con is infuriating, but by the end of the book, bafflement replaces outrage. Almost every Republican leader today supports convicted felon Trump. Decent conservatives have been extinct for a while. Over the decades, many of the most prominent figures on the right, from aristocrat William F. Buckley in his day, to the now-regretful Never Trumpers like Bill Kristol and Steve Schmidt (the strategist who had the clever idea of welding Sarah Palin to John McCain), failed to object to the rot within—or at least not until it was too late. How is it that all these people were unbothered?

Conason’s book offers the suggestion of an answer. Writing about how then–RNC chair Ronna McDaniel knew Trump was lying the Big Lie, but didn’t interfere with the scam, Conason explains: “Intimidated by Trump and profiting heavily from his grift,” the RNC “continued to spread disinformation.” Its response to Trump’s lies “was merely to tinker around the edges of the fundraising copy, never to fundamentally challenge the message.” Intimidation and profit. The paired goads—the stick of fascist abuse, the carrot of free grifted money—may be only logical explanation for the conservative movement’s total abandonment of even the appearance of principles.

Whether or not Trump survives this election, the transmogrification of the right, Conason writes, is likely permanent. “The industrial production of falsehood and fraud will grind on shamelessly, with or without him, overseen by entrepreneurs who understand that substance and commitment carry no sales value in a political culture dominated by noisemaking, grandstanding, and malice.” This machine was built over decades by people who have chipped away at the ethical norms of public life, lining their own pockets. It will most certainly grind on unimpeded by shame or law as long as the right maintains a grip on the levers of power.