On its face, The Icon and the Idealist is not a book about abortion. Thanks to advances in technology and medical knowledge, Americans have become accustomed to an ideological separation between contraception and termination, sensible planning and irresponsible destruction. What Stephanie Gorton’s exhaustive history of the fight to legalize birth control makes clear, however, is that we maintain that separation at our peril. The fights share a history and a rhetoric: “dichotomies of choice against fate, medical technology against nature, bodily autonomy versus submission to divine will.” They also share a newly empowered set of enemies.

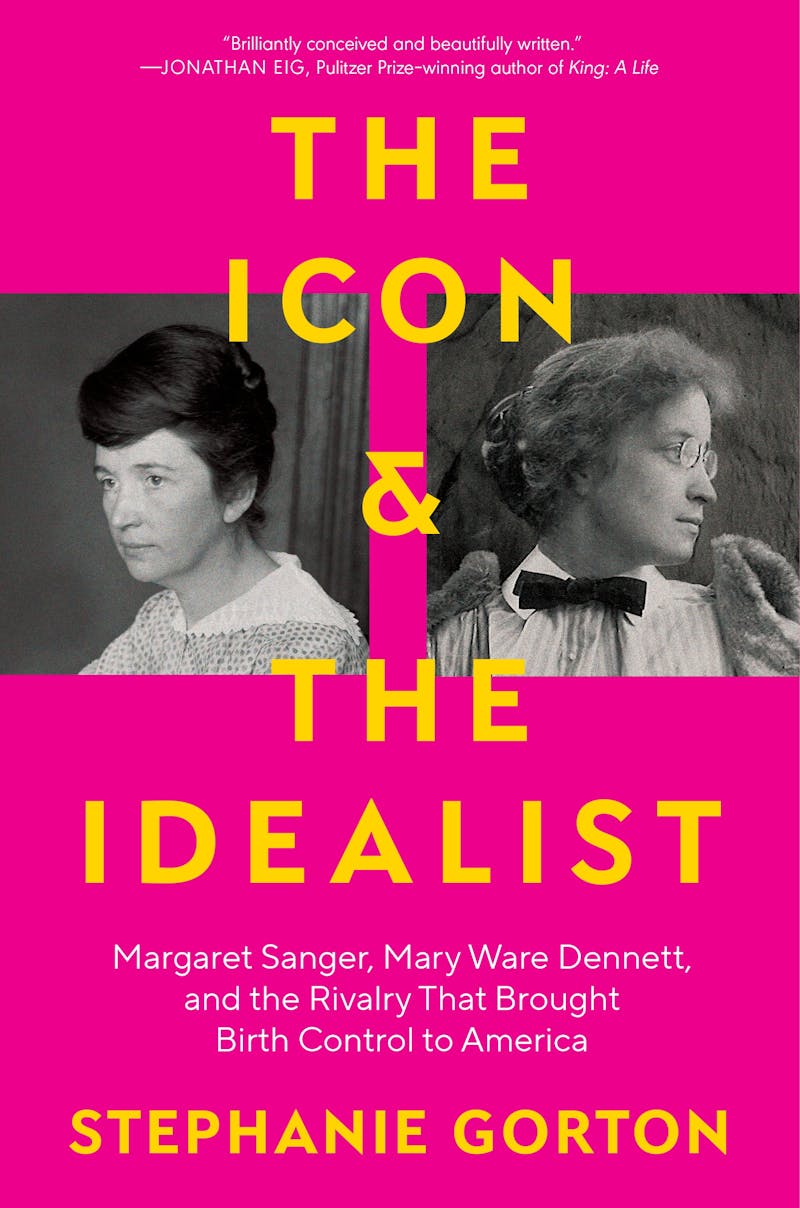

The “icon” of Gorton’s title is Margaret Sanger, the tarnished heroine of the birth control battle, whose failings and blind spots have become notorious. The lesser known “idealist” is her rival and critic Mary Ware Dennett, seven years older, whose story opens up questions of bodily autonomy and human rights that reach beyond Sanger’s single-minded fight. Interweaving the account of their beliefs and battles, Gorton tracks seismic shifts in American attitudes to sex, feminism, and family life across a 20-year span between, roughly, Sanger’s first clinic shutdown in 1916 and her victory in 1936 in the (inimitably named) case of United States v. One Package of Japanese Pessaries.

As their entwined histories show, the two were frequently at odds, personally and ideologically: Dennett was wary of Sanger’s radicalism and hoped to change the law by persuasion, while Sanger’s deliberate provocations brought the law, and the spotlight, down on her head. Dennett came from a family of, in her words, “New England granite”—genteel, intellectual people who were active in abolitionist, suffrage, and antiwar circles. Sanger’s fiercely socialist Irish immigrant parents were also politically engaged, but lacked the money or power to turn their convictions into action. Sanger’s mother, wracked with tuberculosis, endured 18 pregnancies before dying at 50: Sanger was the sixth of 11 children who lived. She trained as a nurse and would later attribute her activism to the memory of her mother and the death of a patient who had begged her for some way of preventing another pregnancy.

Fired up by her experience of poverty, Sanger came to birth control, at first, as an issue of social justice. For Dennett, who had endured three agonizing births and the loss of one baby, before a luridly reported divorce, it was a feminist problem, part of the larger question of how women could take control of their bodies and lives. By the early 1910s, both women were young mothers active in New York radical circles. Dennett was working for the national suffrage campaign, although increasingly disillusioned by its conservative attitudes, and she found a more congenial, outspoken version of feminism in Heterodoxy, a club of prominent women that included artists, lawyers, social workers, and journalists. Sanger’s interests, meanwhile, were sharpening to a point. Before long, she would break ranks with fellow feminists who did not place what she termed “birth control” at the center of their activism.

The split between Dennett’s and Sanger’s approaches—persuasion versus provocation—is widely mirrored in other movements of the time, especially women’s suffrage. Examining them together, and seeing all the ways they overlapped, changed course, and compromised over the long fight, is both fascinating and frustrating. Might they have gone further, faster, if they had worked together, or at least managed to get out of each other’s way? Perhaps. But what their shared story also reveals is the relentless, hypocritical, and cowardly nature of their opposition; it’s damning to see how rare it was for men to speak out in support of something that demonstrably improved their own lives. We have all seen how complacency over “settled law” and the belittling of feminists’ warnings hurtled us into the overturning of Roe. Fired up by that recent history, this book makes it clear that we still have a long way to go to match Mary Ware Dennett’s simple, fundamental belief that women are people.

In Gorton’s elegant summation, Dennett and Sanger were born “at the beginning of a great silencing.” In the post–Civil War era, evangelical reformers took aim at society’s moral corruption, while demonstrably corrupt political leaders seized on the specter of “vice” to distract from their own self-dealing. This culminated in the Comstock Act, which went into effect in 1873, when Mary was one year old, and effectively banned from circulation all information that anti-vice crusader and postal inspector Anthony Comstock judged pornographic. He knew it when he saw it, and he saw it everywhere.

Comstock’s personal history is both tragic and illustrative of his time. His mother died when he was 10 years old, hemorrhaging after delivering her tenth child, and Comstock and his wife lost their only child, a baby girl, at six months. To this damaged man, the innocence of children became a cudgel. To Sanger and Dennett, who each also endured the death of a young child, society needed more openness about sex and reproduction, not less.

A frank discussion of women’s health was long overdue, but it was derailed by Comstock into a moral and demographic panic. The birth rate in the United States had halved over the course of the nineteenth century, for multiple reasons, ranging from a campaign among women’s rights activists for “voluntary motherhood” based on abstinence, to social changes that popularized smaller families. But the reduction was most noticeable among white middle- and upper-class families, sparking a widespread obsession with “race suicide.” Through their doctors, and with the utmost discretion, wealthy women could access newer barrier methods like cervical caps and diaphragms. Condoms were expensive and heavily stigmatized for their association with prostitution, and, like withdrawal—another popular and extremely unreliable method of preventing conception—they depended on men’s foresight and restraint. Women who wanted to take matters into their own hands relied on douching or ingesting potions sold under euphemistic names like “Uterine Tonic.” Although Comstock had chilled the formerly robust advertising market for these concoctions, they were still in circulation, and household manuals carried recipes to mix them at home.

The other way out of unwanted pregnancy, more commonly deployed than any barrier method, was abortion. Before pregnancy tests, bodily changes alone clued a woman in to her situation. Abortion before “quickening”—around four months when kicking can be felt—was broadly sanctioned, until laws against it were passed in tandem with the growing power of a male-dominated medical establishment. Doctors cracked down hard on their “irregular” competition, especially midwives, whose skills and knowledge were dismissed as mysterious, unstandardized, barely better than witchcraft. Every state had passed a law against abortion by 1880.

Preventing or terminating a pregnancy depended on a basic knowledge of biology, yet there was extraordinary censorship of and widespread ignorance about this. As Sanger found her way to the birth control fight in the early 1910s, the radicals around her framed it as a free speech issue, deeply connected to social class: It was, as Emma Goldman said, a “working woman’s question.” Of course, the issue was not just speech, but sex, and women’s right to it. Gorton amply illustrates how radical this idea was at a time when many people did not believe women experienced sexual pleasure or desire, and the judge could declare at one of Sanger’s trials that women had “no right to copulate with a feeling of security.” Against this puritanism, in the words of wealthy downtown feminist Mabel Dodge, Margaret Sanger was “an ardent propagandist for the joys of the flesh.”

In 1912, Sanger began writing a newspaper column, “What Every Girl Should Know,” which frankly outlined the bodily changes of puberty and the workings of the female reproductive system—until it was censored by the post office. In 1914, she further poked the Comstock bear with her magazine The Woman Rebel (tagline: No Gods No Masters), then printed and circulated 100,000 copies of a 16-page pamphlet titled Family Limitation, a frank guide that explained how bodies worked and how condoms, douching, and best of all “a well fitted pessary” might help women take control of childbearing. In early editions, she also suggested taking quinine, an abortifacient, during pregnancy, but this language disappeared in 1921, and Sanger would never publicly endorse abortion again. As she and others elevated the virtues of prevention, so the idea of abortion as deliberate killing began to take hold, with an increasingly bright rhetorical line separating contraception and termination—processes and practices that had, for generations, overlapped.

In late 1914, Sanger was arrested under the Comstock Act, and, facing the possibility of a 40-year sentence, she fled the country. Effectively separated from her husband by this time, she embraced “free love” among a coterie of English radicals. In exile in London, she befriended the influential British birth control advocate Marie Stopes, whose sexually frank 1918 book, Married Love, was a sensation. Spurring on her American rival, Stopes published prolifically and opened a network of clinics. Yet even more fully, she was an unabashed supporter of eugenics, the multitentacled ideology that shadows any discussion of early-twentieth-century birth control activism.

Popularized in the 1880s as an amalgam of Greek terms for “well” and “born,” eugenics infiltrated American ideas about sex and society for at least the next century. In the early twentieth century, it collided with the catchall fear of “race suicide” that encompassed the falling WASP birth rate, the influx of Jewish and Roman Catholic immigrants to the United States, and the mass migration of Black Southerners to the North. Eugenic thinking in its broadest sense—the idea that the human race could be “improved” through scientific and technological innovation—infused many Progressive-era reforms in public health and social policy. It is hard to imagine ourselves back to a world in which infant mortality was as high as it was at the turn of the century, when 20 percent of babies did not make it to age five. The potential of vaccination, and campaigns for clean milk, better sanitation, and reducing alcohol consumption all swirled within the eugenic framework.

In the United States during the 1910s, eugenics organizations increasingly dominated the national conversation, thanks in part to the deep pockets of industrialists like the Carnegies and Rockefellers, who keenly promoted research into “improving” the race. While Sanger was still in exile, Mary Ware Dennett and others founded the National Birth Control League, which prioritized economic and eugenic arguments for contraception. When Sanger returned in late 1915 to face her trial, the league refused to support her. For the time being, she was too personally controversial to find a welcome in the eugenics movement. Her rage was deepened by anguish at the death of her five-year-old daughter, Peggy, from pneumonia, after many months of separation.

In 1916, Sanger tested the line between information and action by opening a birth control clinic in Brownsville, Brooklyn. In 10 days of operation before it was shut down and Sanger and her associates arrested, the clinic helped several hundred mostly immigrant women to understand the basics of reproduction and how to fit a diaphragm. Once again the trial, in a courtroom packed with women, gained attention for the movement, which was gathering more public support. “We are done with the irresponsible stork,” The New Republic, then only one year old, wrote in defense of birth control at the time: “We are done with the taboo which forbids discussion of the subject. We are done with the theory that babies, like sunshine and rain, are the gifts and visitations of God, to be accepted submissively and with a grateful heart.”

Sanger was imprisoned for 30 days, serving a quieter sentence than her sister Ethel Byrne, who assisted her in the clinic and went on a hunger strike during her jail term, becoming the first prisoner in the United States to be force-fed. By contrast, Sanger decided it was time to clean up her image. On her release, she abandoned her more radical, feminist claims for birth control and instead sought the support of doctors and leading figures in the eugenics movement; America’s entry into World War I and the accompanying nationwide crackdown on left-wing causes and groups no doubt influenced her decision. Meanwhile, the rampant wartime rise in sexually transmitted infections prompted the government to push an abstinence-heavy sexual health agenda among teenagers—not in itself helpful to the cause, perhaps, but another way in which formerly taboo issues were nudging into the cultural mainstream.

The outbreak of war in Europe also changed the course of Mary Ware Dennett’s activism. She focused for the time being on lobbying for peace, a cause that ran deep in her progressive family, and which had a long history as a women-led movement. But she did not turn away from her interest in more intimate questions of sex, reproduction, and women’s bodily autonomy. Along with many fellow feminists in the mid-1910s, she became intrigued by a new movement to alleviate the pain of childbirth. This was a personal mission for her, after the physical trauma she had suffered in her deliveries, which had required extensive postpartum surgery. In early 1915, she became an advocate of Twilight Sleep, a drug cocktail invented in a German clinic that promised to take away the pain, and even the memory, of childbirth. The drug fell out of favor when Germany became a wartime enemy, and the idea of medicating away the pain of labor would not gain widespread popularity until the postwar years. But Gorton argues that it was influential anyway, both for popularizing the importance of pain relief during childbirth and for Dennett personally, as it launched her lobbying career.

After the Nineteenth Amendment passed in 1920, Dennett hoped the women’s vote might sway senators in Washington to support birth control. Under the auspices of her new Voluntary Parenthood League, she spent several years slogging away to pass a bill that would strike the word “contraception” from the list of material classified as obscene under the Comstock Act. She believed that this “clean repeal” offered the simplest solution to the Gordian knot of morality, bias, and fear around birth control, but she struggled to find senators willing to support it. At the same time, she continued her own small-scale assault on Comstock, by distributing a sex-education pamphlet she had written for her teenage sons and published in 1918. Frank, informative, and notably insistent on the pleasure of sex for both men and women, the pamphlet would eventually land her in very public legal trouble.

While Dennett was in Washington, she did not know that Margaret Sanger was actively working against her efforts. Sanger’s marriage, in 1922, to a much older, deep-pocketed oil magnate bolstered her activism, allowing her to keep her campaigns, clinics, and publications afloat and even to smuggle contraceptive devices into the country in empty oil drums. Sanger argued that Dennett’s “clean repeal” would unleash a flood of unreliable, possibly dangerous contraceptives into the market, and insisted instead that they must be prescribed by a doctor: Before long, she would go to Washington herself to lobby for a bill that included the doctors-only restriction. Despite declaring, in her 1920 book, Woman and the New Race, that “The most important force in the remaking of the world is a free motherhood,” Sanger committed herself, from that point on, to gatekeeping that freedom.

She was not alone. The buoyant economy of the roaring twenties swept an extremist moral puritanism into power, embodied in Prohibition, major immigration restriction bills, and a vociferous embrace among white voters and politicians of the darkest eugenics policies. In the hope of defeating her most entrenched foe, the Catholic Church (whom she mocked in the Birth Control Review as a “dictatorship of celibates”), Sanger embraced eugenics, even as the movement grew increasingly (to use a term of art) weird. The head of the movement in the early twentieth century was obsessed with what he called protoplasm, a kind of life force, of which the “Nordic” strain was the best. In 1926, when Sanger infamously gave a lecture to the women’s auxiliary of the Ku Klux Klan in New Jersey, she recalled it as one of her “weirdest experiences” in a prolific and largely indiscriminate lecturing career.

“Fitness” was the watchword, while the notion of “unfit” ranged widely, encompassing disability and other chronic health conditions, illiteracy, addiction, sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, and criminality. Black and indigent populations were especially under threat, prone to labeling as “feebleminded” and promiscuous. Forced sterilization, in this cultural climate, was discussed in the same breath as vaccination, as a public health measure against disability. The 1927 Buck v. Bell case, notoriously, argued the right of the state to institutionalize and sterilize women to prevent any more “imbeciles”; Gorton makes the fascinating point that “imbecile” itself derives from a Latin for “without a staff for support.” In other words, the state’s refusal to countenance the reproduction of a poor white woman was a refusal of economic support. Seen in this light, these histories of birth control, abortion, and sterilization, are all histories of the failure of the state to support mothers and families.

This became clearer still in the Depression, when eugenicists fanned the flames of panic over the specter of “relief babies”—children supposedly conceived to capitalize on welfare handouts. Contraceptives suddenly didn’t seem controlling enough. Men like Paul Popenoe, the founder of marriage counseling in the United States and a raving eugenic loon, looked overseas at Hitler’s sterilization programs and worried that the United States was being left behind. Sanger, meanwhile, flirted in her speeches with the idea of segregating social undesirables and refusing immigration to “idiots” and “morons.” In 1933, the American Eugenics Society endorsed birth control as Sanger had arrived at it: under the authority of doctors, who knew what was best for individuals and for society.

At the end of the 1920s, a decade marked by increasingly open discussion of sex and birth control, both Sanger and Dennett were caught unawares by renewed attacks on their work. One of Sanger’s clinics was raided, while Dennett was arrested and found guilty of obscenity for circulating the sex-education pamphlet she had written for her boys more than a decade earlier. (Her elder son, who accompanied her to the trial, was now a married father.) The verdict against a respectable grandmother was met with shock, a reminder that free speech and changing values could still be ensnared in the moral prejudices of a bygone era. For Dennett, whose conviction was overturned on appeal, the trial had its benefits—her pamphlet now sold well enough to stabilize her rocky finances.

Her lawyer, Morris Ernst of the ACLU, went on to defend Marie Stopes and James Joyce against the overreach of Comstock. Then, in 1936, he and Sanger mounted a successful defense of her efforts to import a new diaphragm design from Japan. The court ruling in Sanger’s favor followed the letter of a federal amendment she had attempted to pass some years earlier, by giving doctors—and doctors alone—the freedom to dispense contraception.

Dennett was dismayed. Although Sanger declared victory, Dennett continued to lobby for the clean repeal, fearing not only the paternalistic judgment of doctors but also, presciently, the consequences of leaving women’s rights in the hands of judges. Today, although support for birth control hovers around 90 percent, and executive orders have shored up access, the right to contraception is still not enshrined in federal law. Nor is it available to every sexually active, potentially pregnant person, without strings attached or questions asked. Abortion restrictions post-Roe further endanger access, because in the early days and weeks of pregnancy, the line between “contraception” and “abortion” is scientifically blurry. The right-wing ghouls behind Project 2025 are eager to revive the Comstock Act, and as of February 2022, Gorton reports, there are laws permitting forced sterilization on the books in 31 states.

Sanger’s embrace of a paternalistic medical establishment had broad ramifications for women seeking birth control and abortion, which linger to this day. For all her missteps, Mary Ware Dennett kept her focus on women. Her approach to activism—whether the cause was suffrage, pacifism, sex education, Twilight Sleep, or birth control—was often stubborn and self-defeating, but it recognized an essential interconnectedness in women’s lives, between their intimate experiences and their public actions. She hailed contraception as one of the inventions that make the difference “between feeding and dining,” between endurance and enjoyment, between surviving and living. Our arguments for contraception and abortion today, for women’s free choice over their own bodies, could do worse than pick up that refrain again.