There’s never been a better representation of Donald Trump than those generated by AI; no human being has ever been more suited to the medium. Even the images supplied by his fans exaggerate what makes him strange and terrifying to the rest of us: the strangely flat yet voluptuous contours of his face, the persnickety downward pull of his lips, that hair, that skin. At least the AI version can be made to do anything you want: lick Elon Musk’s toes, ride a unicorn, open a casino in Gaza.

Trump himself seems entranced by almost any form of digital manipulation. A week before his inauguration, he reposted an image of flames and smoke erupting on the hills behind the Hollywood sign, only the iconic lettering reads, Trump Was Right.

The sign might have been celebrating Trump’s standing hypothesis about what causes wildfires (in 2020, he warned, “You gotta clean your forests”), but I don’t think that’s what he wanted to put a fiery exclamation point on. He was claiming to be right about something bigger: liberal Hollywood, the political mood of the country, people’s exhaustion with the strictures of wokeness.

The image of the hills burning aligned with prevailing narratives about why Trump won and what his victory meant for the entertainment industry. According to this story, Trump succeeded because the left had overplayed its hand, imposing an unpopular cultural agenda by way of Hollywood and the mainstream media while failing to compete on the new content terrain, where younger male voters would be won or lost. Hollywood had become irrelevant, and if it hoped to survive, it would have to abandon its woke agenda and get more in tune with the American people, who prefer Megyn Kelly to Rachel Maddow and the earnest Jesus-biopic series The Chosen to The White Lotus’s knowing satires of the wealthy.

To a certain extent, that narrative reflects reality: Hollywood decision-makers and studio execs do seem to be abandoning progressive content for more apolitical or conservative fare, whether overtly, to curry favor with the administration (take, for instance, the documentary Melania Trump pitched Jeff Bezos about her return to the White House; Amazon paid $40 million for the licensing rights), or because they think that’s where the action is (Joe Rogan, after all, has almost 20 million subscribers).

But Hollywood’s failure to stay relevant has less to do with the political valence of its content than with the complete transformation of the media ecosystem. Woke was Hollywood’s most recent gambit to appeal to people; a right-wing turn may be its next. And yet conservative dominance of Hollywood may prove to be a much rosier future than the one we’re actually going to get: a future where pop culture is little more than a careless swirl of stock images, slapped together with no rationale beyond ginning up engagement—the wholesale replacement of storytelling with slop. To an extent, this future is already here, and it’s impossible to make sense of the extraordinary power held by right-wing podcasters in American politics or understand the meaning of Hollywood’s “unwokening” without recognizing that slop—content shaped by data, optimized for clicks, intellectually bereft, and emotionally sterile—has been overwhelming Hollywood’s cultural impact and destroying its business model, not to mention countless careers along with it, for years.

The Great Unwokening

In recent months, with Trump’s victory seeming to indicate that the country is far more conservative than Los Angeles and “woke” Marvel blockbusters that are disappointing at the box office, conservatives have jeered, “Go woke, go broke.” They have it backward.

Contrary to the right’s conspiracist shouting about elites, #MeToo and Black Lives Matter weren’t cooked up by Hollywood executives. These were grassroots movements, expressions of popular opinion, that hit the industry at a moment when it was vulnerable. The effort to correct decades of white male dominance was able to gain unprecedented purchase because the industry was in free fall and willing to take dramatic steps to regain eyeballs.

The foundation of the business had been cracking apart for years. In 2016, Hollywood saw some of its worst ticket sales this century. The industry had changed: Audiences were staying at home more, franchises were becoming a financial necessity, and mid-budget films were vanishing. “The tide has moved against movies,” one analyst said. “They used to be the hub of what entertainment is, but that core has shifted to streaming and television.” In 2018, the film industry seemed to rebound financially, but television was beginning to feel the pain. In 2019, the pace at which Americans were abandoning traditional pay-for television increased by more than 70 percent, and more Americans paid for streaming services than subscribed to traditional cable television.

Interviewed that year, Donna Langley, the head of Universal Studios, suggested optimistically that there had never been a better time for filmmaking. But the reality was something like the opposite. Mid-budget movies were vanishing, labor precarity was increasing, and the industry’s financial cracks were deepening.

Then, 2020.

Lockdown inflamed the “streaming wars” of the previous decade. During the pandemic, the largest streaming services increased their subscriber base by around 50 percent. Studios turned over rocks for content, streaming events and—unthinkable in a previous era—releasing blockbusters direct to home viewing. These were sugar highs for studios and viewers alike: a captive audience, plentiful selection. The pandemic, the political whiplash of Obama-Trump-Biden, the pileup of the #MeToo movement, the murder of George Floyd, and the nascent power of BLM—all coincided with an existing decline in the popularity of traditional mass entertainment and conspired to destabilize decision-making at the top. The multiple blows to the collective conscience and the collective pocketbook cleared out space for a moment of political reckoning.

Over this period, there is no doubt that calls for more representation led to increased diversity in the industry. UCLA’s annual reports bear out near double-digit increases across streaming in women and BIPOC folks writing, directing, and starring in productions. But those changes were visible only on-screen or in the highest-profile creative positions, such as writers or directors. Behind the scenes, very little changed. The same “Studio Chief Summit” where Langley was so sunny about industry disruption allowing movies “to find their way into the world” featured the leads of those studios The Hollywood Reporter deemed the top seven production houses. Among five men and two women, all were white. (The summit’s organizers may have included Amazon’s Jennifer Salke as a gesture toward representation; Amazon’s content spending that year was less than half that of almost every other studio at the table.) In 2023, Hollywood’s dozen highest-paid CEOs had the same skin color and the same equipment: all white, all male. Only one Black person has ever won an Oscar for best picture (which goes to a film’s producer): Steve McQueen in 2014 for 12 Years a Slave.

Adam Conover, onetime cable television show host and current YouTuber, told me about going out to audition during peak diversity efforts. Even then, he wondered how genuine the reforms were. Sometimes, agents would appear to deliberately stoke racial division. “Their clients would say, ‘Why aren’t I working?’ And they’d say, ‘Oh, they can’t hire white guys anymore.’” As Conover pointed out, “the guy who was making the decision ‘Oh, this person can’t put a white guy in the chair’ was, of course, a white guy.” In essence, he observed, the white people who still ran the industry were saying, “Oh, I need to hire more diversity below me.”

My podcasting colleague Akilah Hughes told me she was not “heartened by those sorts of actions where they’re like, ‘Well, we put a Black person in a pudding commercial.’” Hughes’s fears about the emptiness of such gestures toward diversity have been borne out. In February, she described recent meetings in which people said, “We’re not making any movies with Black leads.” It didn’t matter what the story was about; Blackness itself was the problem: “Blackness represents woke. You’re sending a message just by virtue of existing.”

Hughes’s disheartening experience reveals the familiar limits of the entertainment industry’s attempts to stunt-cast itself out of systemic oppression. Representation only gets you so far. But the executives’ candor with her also reveals what they think will get them out of this jam. If Black people on-screen are to blame for their trouble, perhaps yanking Black people off will make the money tree bloom again.

The Great Unwokening may align with Trump’s reelection, but it has as little to do with the aggregate opinions of the American people as did the Great Awokening. Rather, the degradation of Hollywood’s traditional movie- and show-making apparatus—the system’s inability to latch on to sustained audiences—has prompted the decision-makers to sloppily aim for what seems to be popular. (Then, Black Lives Matter; now, Jordan Peterson.)

Conover, the YouTuber, was emphatic: The Trump-driven “vibe shift” can’t be separated from the harms the entertainment industry has done to itself. In chasing streaming as the future of content, the industry “put a bullet in its own brain”: “If you look at what these companies, these previously thriving companies, have done to their own business,” he told me, “they’ve essentially destroyed vast amounts of profitability, and they’ve abandoned entire forms of media to YouTube.”

The reason decision-makers are running away from diversity today, in the wake of Trump’s victory, is that they don’t know where to run to. They barely realize what they’re running from. Entertainment executives likely won’t resurrect their careers by casting white actors, because they’re increasingly uninvolved in casting at all. In the Platform Era, there are no casting decisions separate from algorithms. In February, the actress Maya Hawke told The Hollywood Reporter that some producers now demand that actor ensembles be determined by influencer status. When she told a director she wanted off of social media, the person replied, “If you delete your Instagram, and I lose those followers, understand that these are the kinds of people I need to cast around you.” In other words, if Hawke came on board but didn’t bring her followers, she might find herself playing opposite actors hired as much for their clout as for their talent.

The Giant Sucking Sound

The moment liberal Hollywood truly collapsed wasn’t Election Day 2024. It was January 18, 2022—the day YouTube announced it would stop producing original content and effectively abandoned the idea of investing in creativity altogether. The experiment, which had been brief, involved projects created almost solely by existing celebrities. When closing its original content studio, YouTube vowed to continue on with its “Black Voices” fund, which it had endowed with a grand total of $100 million, intended to finance creators who showed promise. The last “class” of creators was announced in early 2022. The application page now redirects to a page celebrating creatorship more generally.

With the decision to cancel original content, YouTube turned the gig economy into the default for all of popular culture. If you’re not bankrolled by an outside entity or desperately feeding an obsessive fandom, you can’t survive.

To understand why YouTube’s decision was so consequential, you have to go back to the company’s transformation over the previous decade from “that thing teens watch” to the most popular source of television, recently overtaking Disney along with every other traditional producer. The legacy media giants that once shaped culture are now rounding errors. The services created by legacy brands to compete with Netflix, such as Peacock, Max, and Paramount+, each get less than 2 percent of total viewing time.

These audience shares are especially pitiful compared with the vast sums companies are spending to bring in eyeballs. In 2024, programming and production costs for most major content producers—including makers of blockbuster movies—ranged from an estimated $22 billion for NBCUniversal to $1 billion for AMC. One industry analyst put YouTube’s content spend at nearly $20 billion, with the caveat that this represented not development or acquisition but “revenue-sharing,” a rather fancy way of saying that YouTube puts ads that it has already sold into original content that it pays nothing for and supports in no way.

Independent creators who make a living on YouTube do so on earnings cobbled together primarily from brand deals in addition to ad-revenue sharing, though YouTube is canny at deploying its resources to use creators as consultants on the project of attracting more creators, a pyramid scheme aimed at supplying endless would-be influencers. Hughes, my podcast colleague, received a “fellowship” that consisted of giving feedback on YouTube’s in-development features and appearing at conferences where various bigger celebrities would talk about the importance of authenticity—a substance that Hollywood has long strip-mined from minorities and outsiders. Another word for “authenticity,” however, is “no one else pays my bills.”

Hughes had a following of around 150,000, a book deal, and was making inroads into a television career when she developed a health issue. “When those creators get sick, which is what happened to me,” she said, “suddenly the only benefit to having a YouTube channel is that, well, now I have people to pay for my GoFundMe.”

From a distance, she was experiencing the very success that proponents of our democratized, decentralized version of the entertainment industry promise. A voice from outside the mainstream who built her channel on her own humor and wit, she was now courted by networks because of the automatic audience her follower count represented. As it happened, her audience were the only ones there for her when she got sick.

When I spoke to Hughes, the smoke from the L.A. fires was still being rinsed from the air, and she pointed out that the fires had forced many prominent-but-not-famous YouTubers to turn to their channel audiences for help. Benji Le, for instance, created videos that guided viewers through taking care of the lush indoor and outdoor gardens of his Altadena bungalow. A video posted of the day he and his partner returned home to see what was left ends with their finding a ceramic cat and frog, one page of a book, and what looks to be a clay saucer. “I don’t really know what the future of this channel is,” he says. “Without the plants and without the house, you know? I mean, that’s like, what a lot of my content centers around. So, now that I don’t have anything. Like, I don’t have the plants.”

Le’s audience came through for him, raising more than $130,000 on GoFundMe, and now his channel is back, with videos documenting the small joys of their new apartment, including the purchase of his first new plant.

Some more famous YouTube personalities who were also affected by the fires didn’t have to go phone-in-hand directly. The Royalty Family, for instance, who have 29 million subscribers, also had to evacuate after the fire. The channel specializes in comically exaggerated versions of domestic existence combined with strange one-off challenges: “My Daughter’s First Christmas Surprise!” or “My Mom Found Out I FAILED School...” and “I ATE Every DRIVE THRU in a Day” or “Surviving Overnight in a Cyber Truck.”

In isolation, The Royalty Family’s response to the evacuation and the possible loss of their home isn’t formally that different from Le’s: They’re distraught, they’re worried, they can’t believe it’s happening, they’re grateful things turned out OK. What’s remarkable is that their reactions are exactly like almost every other video on the channel. It’s not so much that escaping the fires didn’t faze them; it’s that they seem the same level of fazed by the fires as they are by “Our Son’s BIG Accident” and “There’s Something LIVING in our Attic.” (It was a bird.) All the thumbnails, fire or babysitter or bird, are presented in the same hyperventilated style; the teen son’s mouth is always frozen in an identical grimace of distress.

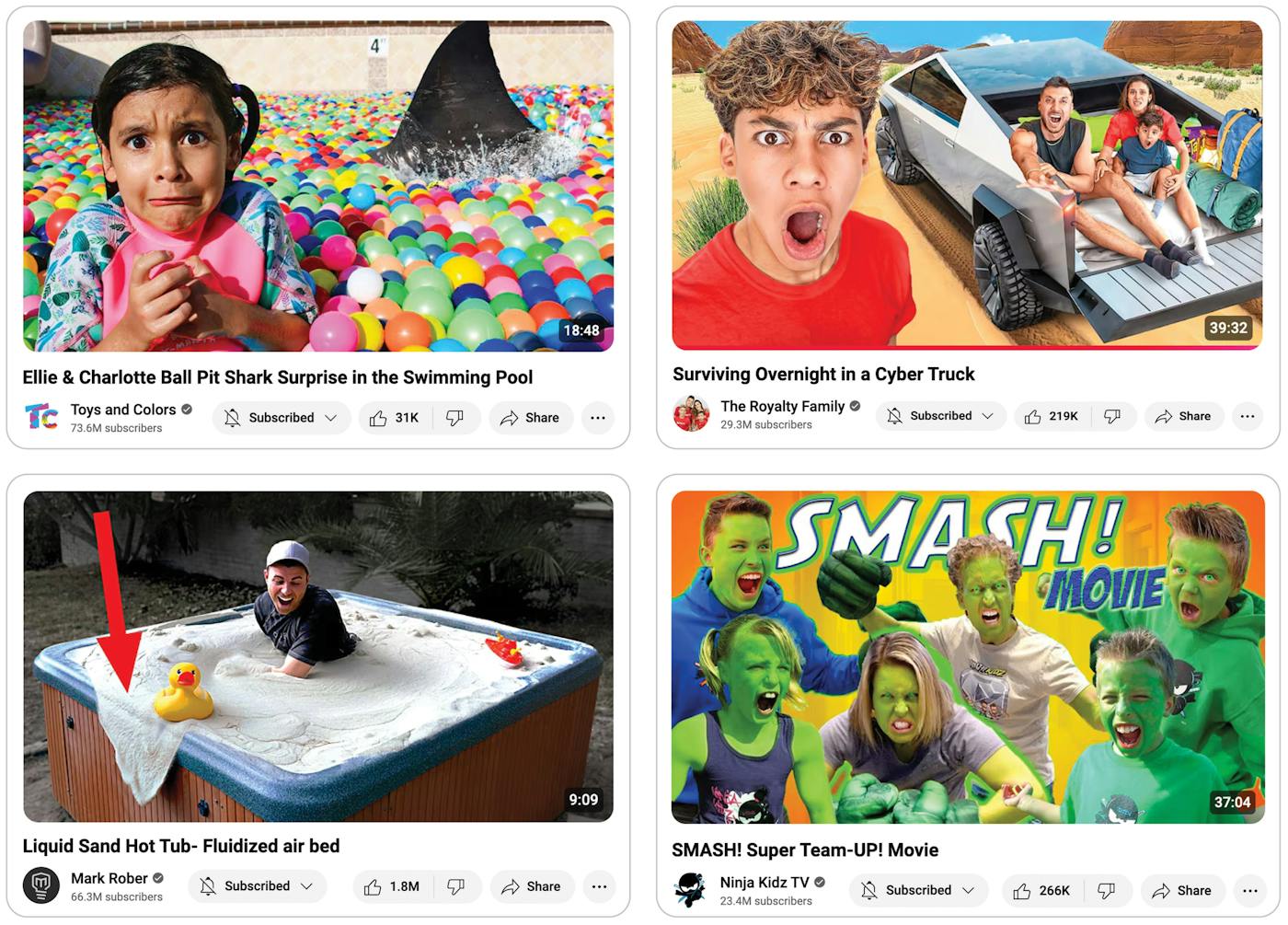

Although this L.A.-based family-disaster-porn channel is extremely popular, it doesn’t break into YouTube’s top-50 list. Nor do others in the family-disaster genre, such as Jordan Matter and Ninja Kidz TV, which each boast tens of millions of subscribers. That’s mainly because the distribution of viewers is so absurdly top-heavy. YouTube refuses to confirm the numbers (the lower tiers can become out-of-date within days), but out of an estimated 65 million-plus active channels, as of last year only about 2,000 had 10 million or more subscribers. Fifty-three have 50 million or more, and 10 have 100 million or more. Anyone in the top 2,000 can make $100,000 a month just by sharing ad revenue; the top channels have spin-off channels that pull in their own views. The sponsorships and other brand deals can push salaries up even more. The family channels succeed by synthesizing video genres at the top of the charts: MrBeast’s real-life Squid Games (literally, one of his most popular videos is exactly that—and with viewers that include MrBeast’s preteen fan base, it had far more reach than the Netflix show that inspired it, at 380 million subscribers), elaborate stunts that dip into the surreal (such as Mark Rober’s “Liquid Sand Hot Tub- Fluidized air bed”), and hallucinatory children’s channels that frame familiar situations as a version of MrBeast’s curated distress. Toys and Colors, with 73 million subscribers, promotes “Going to the Dentist for Teeth Checkup with Alex Jannie and Lyndon!” and “Ellie & Charlotte Ball Pit Shark Surprise in the Swimming Pool.” These channels’ thumbnails invented the template of shocked grimace aped by the hype families.

The iterations are endless, the content usually manufactured terror only loosely tethered to reality (PAYTON WENT TO THE HOSPITAL! OCTOPUS STUNG SALISH! YOUTUBERS WHO ARE SECRETLY CRIMINALS!). All of it is designed for consumption and reconsumption, remixed by algorithm-gaming channels (which themselves have hundreds of thousands of subscribers) into garish clipfests narrated by AI voices reminding you constantly to WATCH TO THE END. The humans in them mug endlessly for the camera, their eyes analog versions of the stretched-out grotesques in the thumbnails.

This is content chewed up and spit out so often that it has no texture—a puree of overly vivid colors, chaos, and dread. The pink slime is here. It’s not all AI-generated, but it might as well be. Between MrBeast, stuntmen, the hype houses of blood relations, and the weirdly adventurous kids, these channels boast hundreds of millions of subscribers who add up to billions of views. This is the content Hollywood studios are really up against, whether they know it or not. In March, YouTube creators held “up-fronts,” teasing their coming content as a way of persuading advertisers to lock in placement. (The tradition of up-fronts was started by television networks to lure in and secure ad dollars up front.) An estimated 150 major brands were in attendance. Billions of dollars were at stake.

In this stripped-down content ecosystem, the creators who now give the right wing more popular appeal have found their opportunity.

Conservatives, the Other White Meat

Liberals alarmed by the rise of conservative mouthpieces often point to billionaire-supported, aggressively anti-woke propaganda like The Daily Wire and PragerU. But calls for building left-wing outlets to parallel such media target the wrong enemy. The fight isn’t between PragerU and some imagined progressive alternative; or if it is, liberals are aiming too low. The real battle for eyeballs is between content identifiably produced by real people and the pink slime churned out by mainstream entertainment. A lefty version of The Daily Wire, properly funded by lefty billionaires (if enough of them exist?), might compete politically, but the real challenge is pulling audiences away from the numbness induced by MrBeast and the hype families.

On that front, the right is ahead. The conservative content on YouTube encompasses the woke-hostile bro comedians who made up the majority of Trump and JD Vance’s podcast tour. Vance appeared on Rogan’s show, and Trump did lengthy interviews on Theo Von’s This Past Weekend and Andrew Schulz’s Flagrant. The ordinary content on these shows isn’t nearly as popular as the eye-popping antics at the top of the heap: They are all counterprogramming the hyperboles of the hype-house style with recognizably human faces—if they also adopt a bit of the pervasive alarm and addictive adrenaline of repeated confrontations with fake peril (for example, “DEI pilots!”).

You might notice that I’m using “podcast” and “YouTube channel” somewhat interchangeably here (as did the media covering the presidential podcast tours). That’s because the two are becoming one and the same. YouTube is now the most popular platform for accessing podcasts; Rogan has 19.6 million subscribers to the video version of his podcast, millions more than his numbers on Spotify. Tellingly, the Trump appearance boosted Rogan’s YouTube presence by 400,000 subscribers, by at least one estimate. Spotify didn’t say. Von has around 60,000 monthly listeners and three million YouTube subscribers, where his videos have hundreds of thousands of views.

A lot of what now counts as right-wing pop culture didn’t start out as political. Rogan built his career on Fear Factor, a game show of disgusting dares that were shocking at the time, the primogenitor of the dominant channels’ deliberately arousing antics. Von and Schulz are comedians. When liberals think about conservatives’ entry into mass media, we might think of Ben Shapiro or The Free Press, brands that are also popular, yes, but don’t carry the enormous parasocial sway of the bros.

Politically, the real pop culture contest today isn’t between who has the best entertainment franchise—the Reaganesque frontier stoicism of Paramount’s Yellowstone or the perverse feminism of Showtime’sYellowjackets, say—it’s between who can effectively move their audience: Rogan or MrBeast? Liberals aren’t even competing on this front. I’m not sure they even know it’s there. Trump’s appearances on these podcasts helped him because they brought him into an environment. He was joining them. Harris, of course, didn’t go on Rogan, and when she did venture into the podcast sphere, it often felt as if she was trying to convince that audience to join her.

Since Trump’s reelection, liberal pundits have focused on the signifiers of support Hollywood has traditionally supplied: the label ribbons, the performative representation, and whether or not Disney includes content warnings on racial stereotypes present in its classic films. But the rise of the right-winger as trusted hangout interlocutor, and the way the connection he offers shapes how audiences move through the world, are different from the “different hat, same ball game” signaling of past presidential cycles.

To be sure, the presence of people like Pete Hegseth, Dan Bongino, and even Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Dr. Oz in the Trump administration can be traced to the president’s affection for “straight-out-of-Hollywood” casting, but, crucially, none of these figures emerged from the entertainment business we’re referring to when we say “Hollywood.” Trump’s Cabinet casting borrows more from the follower-count logic that is only now sweeping Hollywood. Bongino and Kennedy in particular are products of the YouTube/TikTok conservative-influencer ecosystem. Hegseth and Oz were cable staples but gained currency in the base by making the podcast rounds. When I first heard of their selections, I was struck by the fact that they’re not even top-tier propagandists. Imagine you’re determined to place someone in a Cabinet position solely for how they present on-screen, and you go with the guys who were too erratic to put on in prime time.

But that was the point, I think. Democrats and progressives mock the junior varsity nature of Trump’s team, taking pleasure in the fact its members weren’t good enough to succeed in prestige media, just podcasts and 30-second sharable spots. We don’t want to believe the prestige media don’t matter anymore.

What’s happening now is different from tonal shifts of culture that have occurred before. (24’s celebration of torture during George W. Bush’s reign to Glee’s embrace of queer high schoolers during Obama, for example.) One difference this time is the aggressive nakedness of the backlash. If Conover’s and Hughes’s conversations with studio insiders suggested that the industry was retracting its interest in diversity—and even “messages”—the insiders were just saying out loud what anyone can see on screens. A crew member on the most recent Captain America movie told an industry publication that Disney had tinkered with how the movie presented its villain—a president whose anger morphs him into the Red Hulk—given Trump’s continued popularity. Now the Red Hulk was less a vengeful fascist and more a victim to outside forces. The crew member explained, “I think Disney was realizing, ‘Hey, we’ve been bleeding for a while. Let’s try not to piss off our core base any more than we have been over the last couple of years.’”

As chilling as these obvious plays for favor to the right may be, we should be more chilled by what’s going on underneath them: the collapse of the broader communal experience of movies and TV. This is not a typical swing in messaging as the party in power shifts; it’s a culture falling in on a hollowed-out center.

When I talk to my friends in California, they tell me about everyone they know who is packing their bags. An entire creative class is vanishing. “I probably got about half a dozen friends, previously comedians or writers, and they’re saying, ‘I’m going to grad school for therapy,’” Conover told me. But today even working as a therapist with burned-out creatives isn’t safe. “It was actually a pretty lucrative gig for a decent amount of time,” said Maureen Ryan, a television critic and author of Burn It Down: Power, Complicity, and a Call for Change in Hollywood. “But now those trenches are being depopulated.”

Industry surveys bear this out. More people are leaving Hollywood than ever before. Decades of experience are being wiped away in real time. Employment in Los Angeles’s film, television, and sound sector dropped around 30 percent between 2022 and 2024, according to a report by Otis College of Art and Design. New York, a lesser hub for decades, has seen its own entertainment industry similarly dive: After the historic strikes of 2023, when members of the Writers Guild of America and SAG-AFTRA stopped working for months, direct production employment was 41,800, 25 percent lower than prestrike level. It seems doubtful either hub will recover. But the problem of people leaving the entertainment industry goes beyond a geographic shift. People are disappearing from the entire category of entertainment. Consider those YouTube channels pumping out AI-generated narration over crazed-but-optimized imagery.

Traditional entertainment producers are scrambling to keep up in the contest of who can remove the most flesh and blood; superheroes and digitally animated characters dominate the box office. We’re all already familiar with Netflix’s reliance on AI to produce a dehumanizing experience: AI analysis is what pushes out the “personalized” suggestions, guaranteed to never delight or surprise. We’re not waiting for a post-human entertainment future—we’re already in it.

In that context, of course reactionary influencers dominate; they offer what Hollywood no longer does. The bros and their brethren—Jordan Peterson, Logan Paul, even trad wives and crunchy anti-vax health grifters—give the illusion of human connection. These conservative cultural leaders meet disempowered white people where they are—unhealthy, lonely, and lost in a culture they feel doesn’t welcome them.

The YouTubers and podcasters offer tools for navigating day-to-day life (health supplements, homeschooling, “masculinity” pep talks) alongside scapegoats to blame for their struggles (trans people, Anthony Fauci). They supply a shortcut to empowerment, an external enemy to blame.

It’s working.

Mass culture was never perfect, never entirely progressive, much less revolutionary. It can numb as well as inspire us—but at least it provided a shared language. To fully grasp how far we’ve fallen, consider the typical product that Hollywood once made and why it was able to make it—not because of ideology, but because of a stable economic foundation.

A Golden Era, Not Why You Think

Before the internet, social media, and streaming video, the movie industry was under threat by another new technology packed with lower-quality content: TV. In the 1970s, movie execs responded very differently to the danger of obsolescence—by taking chances on young talent and artistically ambitious ideas. The result was arguably the greatest decade of American cinema.

We’ve seen current critics bemoan the desultory effects of iterative IP today (how many Marvel movies can they make, amiright?). But many of the hits of the ’70s were sequels or based on familiar characters and stories: Jaws 2, Rocky 2, the Godfather movies, the first Star Trek, multiple Bonds. There was a lot of disaster porn. Yet even as the box-office winner list was heavy with dependable genres (and heavy VFX for the time)—sci-fi, shoot-’em-ups, and several paeons to the heroism of World War II—there was also fodder for sophisticated post-cinema conversation (Annie Hall, The Deer Hunter, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest). Wildly different kinds of stories all played to the same vast crowd.

The biggest hit of 1974 was Blazing Saddles, a movie that some anti-woke sorts say “couldn’t be made today.” I think they’re right, but it’s not the “un-PC” comedy that’s the problem, though the fact that the leading man is Black might be. The real problem is that the horses don’t talk, too. One of the striking things about the top-grossing films of the 2020s is how many of them replace identifiably human characters with superhuman or animated characters or CGI monstrosities.*

Humans are expensive and unique. Every single person in the background of a movie needs to be hired, paid, fed, and present for innumerable takes, any one of which might be marred by an errant cough or slip. AI-generated extras? One and done. During the actors and writers’ strike, a chief negotiator for the strikers told CNN that his counterparts were proposing “that our background performers should be able to be scanned, get paid for one day’s pay, and their company should own that scan, their image, their likeness, and to be able to use it for the rest of eternity in any project they want with no consent and no compensation.” Difficult to replace a human being if one breaks. Much easier to digitally generate a deceased actor than hire a new one. Human beings are unpredictable, stubborn, and demanding. That is why they are being removed from the process of making entertainment.

If you want to understand why Hollywood used to produce a range of stories where now it produces the same three things, don’t just look at a media ecosystem that encouraged studio executives to take risks—look at the rank-and-file contracts. In the ’60s and ’70s, SAG-AFTRA secured residuals for actors in film and television and, in 1980, secured residuals from the videocassettes and pay-TV markets then threatening Hollywood’s traditional model. These protections didn’t just help artists; they made risk-taking possible.

The economics of the entertainment industry have never exactly favored anyone less than a superstar, but the gains made by unions in the 1970s paved the way for some stability for the vast middle of the Hollywood ecosystem: those working actors, writers, and directors whose names might go forever unsigned into boulevard concrete, but who could piece together a living based on smaller projects and residuals. Hollywood wasn’t taking risks in the 1970s because the industry was more progressive. It was taking risks because talent could afford to fail.

Pop culture that could sway with the political sensibility of the time—never too far either way—rested on a framework durable enough to provide for a full ecosystem of creatives and craftspeople. When a TV show got locked in for a season of upwards of 20 shows, everyone from the showrunner to the guys lighting the set could count on a paycheck for a while and were guaranteed a certain level of security year-round. Today, the health care provided by the Writers Guild of America is still pegged to getting a job on a one-hour network episodic series (currently averaging about 10 episodes per season). To qualify, you need to make as much as someone with that kind of job, estimated by L.A.-based WGA West at $43,862, and that money has to come from a production company that’s hiring guild members. Streaming services series might now run eight or even fewer episodes per season, and, of course, neither YouTube nor any other web production company has set seasons, and they don’t have to hire union members at all.

The direct link between even the tenuous safety net that entertainment unions offer and a popular culture that sustains a humane view of the world is that the economy producing that culture can sustain humans. I mean this quite literally: Can you create storytelling that lifts up the value of individual people if fewer and fewer people are involved in the making of popular culture?

The pink-sludge tidal wave is born of a fantasy in which no risks ever have to be taken, a fantasy that has long been the dream of those at the top. You can see it in those films of the 1970s: the sequels, the dependence on genre, “bankable” stars. But the truth underlying most of what humans created for other humans was that no one could reliably predict blockbusters. The uncertainty made room for mid-tier movies and oddball shows. Would Saturday Night Live have made it to the air if people had known what to make of it? A recent n+1 article quotes the screenwriter William Goldman in his book Adventures in the Screen Trade on this: “Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what’s going to work.” The n+1 writer, Will Tavlin, takes away from his study of Netflix’s growing body of terrible programming that the company’s “greatest innovation was that it found a way around this uncertainty: it provided a platform on which there are no failures, where everything works.” Another way of putting it: The modern entertainment industry, traditional production and development, is a system in which nothing will “work”—because it doesn’t have to.

Everything will be made as cheaply as possible and with as few variables as possible. It will be disposable viewing that might have a conservative gloss or perhaps a vaguely liberal one, but anything resembling an opinion will come with the chemical aftertaste of banana-flavored candy or worse.

The industry wasn’t perfect in the 1970s, but at least it had a foundation that could sustain creativity and risk-taking. That foundation is now gone—so instead of Chinatown, we get AI-generated YouTube explainer videos about a family that gets lost going to Chinatown (WE GO EXPLORING AND YOU WON’T BELIEVE WHAT WE FIND). Instead of risky, ambitious storytelling, we get content optimized for engagement metrics. The question isn’t whether Hollywood is becoming more liberal or conservative. The question is whether Hollywood, as we know it, will exist at all. The elimination of our grubby fingerprints from film stock and cameras in favor of generative pap is straight out of the cryptobro playbook: maximum extraction of value with minimum investment in creation.

As America loses the superficial liberal flavor of pop culture, we’re losing culture’s transformative power entirely. Good storytelling challenges its audience; it encourages people to question their assumptions instead of accepting the status quo. The surprises matter because characters are changed by what they find; the mere novelty isn’t the point. We’re left with a future in which completely AI-generated families undertake increasingly surreal rituals designed to recall distantly remembered household traditions. This isn’t about ideology. The algorithm doesn’t care what you watch—just that you never stop watching. Just keep the screen on. Auto-play to infinity.

What we’ve learned in the past eight years is not so much that conservative content is more appealing, but that it is still trying to make an appeal. It’s trying to hit emotional buttons and, astonishingly, connect with people away from the screens they’re in front of. It might even get them to do something while not in front of a screen. Pink slime doesn’t seek to connect, it just glides right over. It has no intuition. It can’t answer some need. Only humans can do this. In fact, much of the conservative entertainment that’s broken through to the mainstream works because it seeks to do more than soothe. For better or worse, the bros and their trad-wife cousins in this quasi-counterculture inspire loyalty based on a sense of community.

And we are so starved for intimacy and the delight of discovery that when actual humans run into view, they can tell their audience to worship or attack.

Here’s a provocative question: Will we eventually miss conservative entertainment, too?

As culture erodes, something else rushes in to take its place: hollow symbols, like the ones we see everywhere now, replicas that imitate meaning but have none of their own. That’s why the image of that burning Hollywood sign, photoshopped to say Tump Was Right, felt so inevitable and so distant at the same time. Inhuman, inhumane.

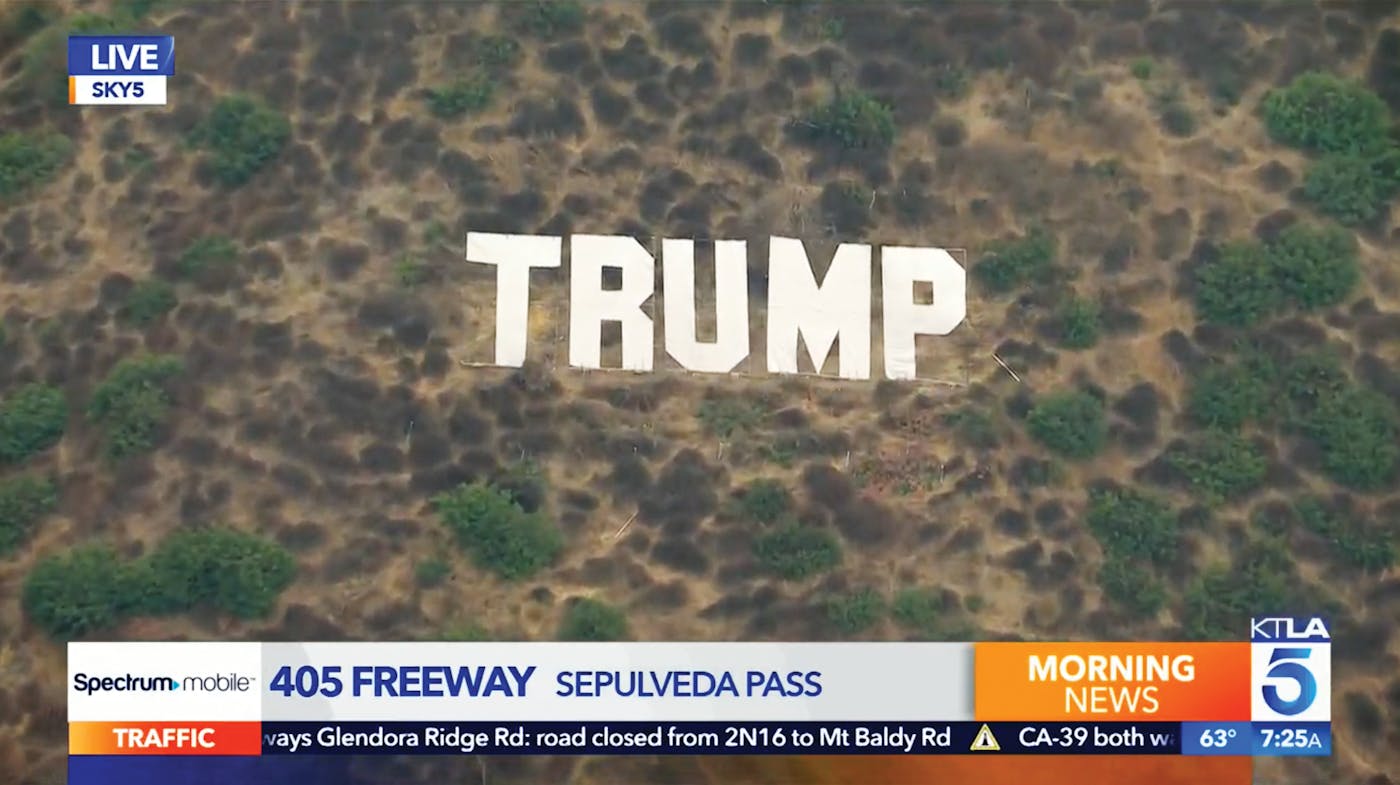

Trump’s delight in this conjured victory over traditional entertainment wasn’t new. It was a warped reflection of another Hollywood-style sign that briefly stood in 2020, just before the election: a physical billboard, constructed in the hills behind Sepulveda Pass in the classic white block letters, which said, simply, Trump.

Someone reported the sign to the Department of Transportation not out of political grievance but concern that it was tinder—the fires of 2017 a close memory, prevention at the top of everyone’s mind. The California Highway Patrol deemed it a traffic risk, and it was quietly removed. After Trump’s 2025 inauguration, the sign resurfaced online briefly, but Trump didn’t repost that image. I suppose he preferred the more violent, the more cinematic version—the one that no one built, and no one had to remove.

* This article originally misstated the number of top 50 English-language movies that have exclusively human main characters.