I was driving my daughter to hockey practice, scrolling through my emails at a stoplight, when a jarring subject line popped up: “Notice of Grant Termination—Effective April 3, 2025”—that is to say, that very day. There it was. The shoe that many of us reliant on federal research funding had been waiting to drop now hit my inbox with a thud: The $60,000 of funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities that I had been awarded to support writing a history of the educational culture wars was gone, ironically itself a casualty of our current clash over knowledge, culture, and politics.

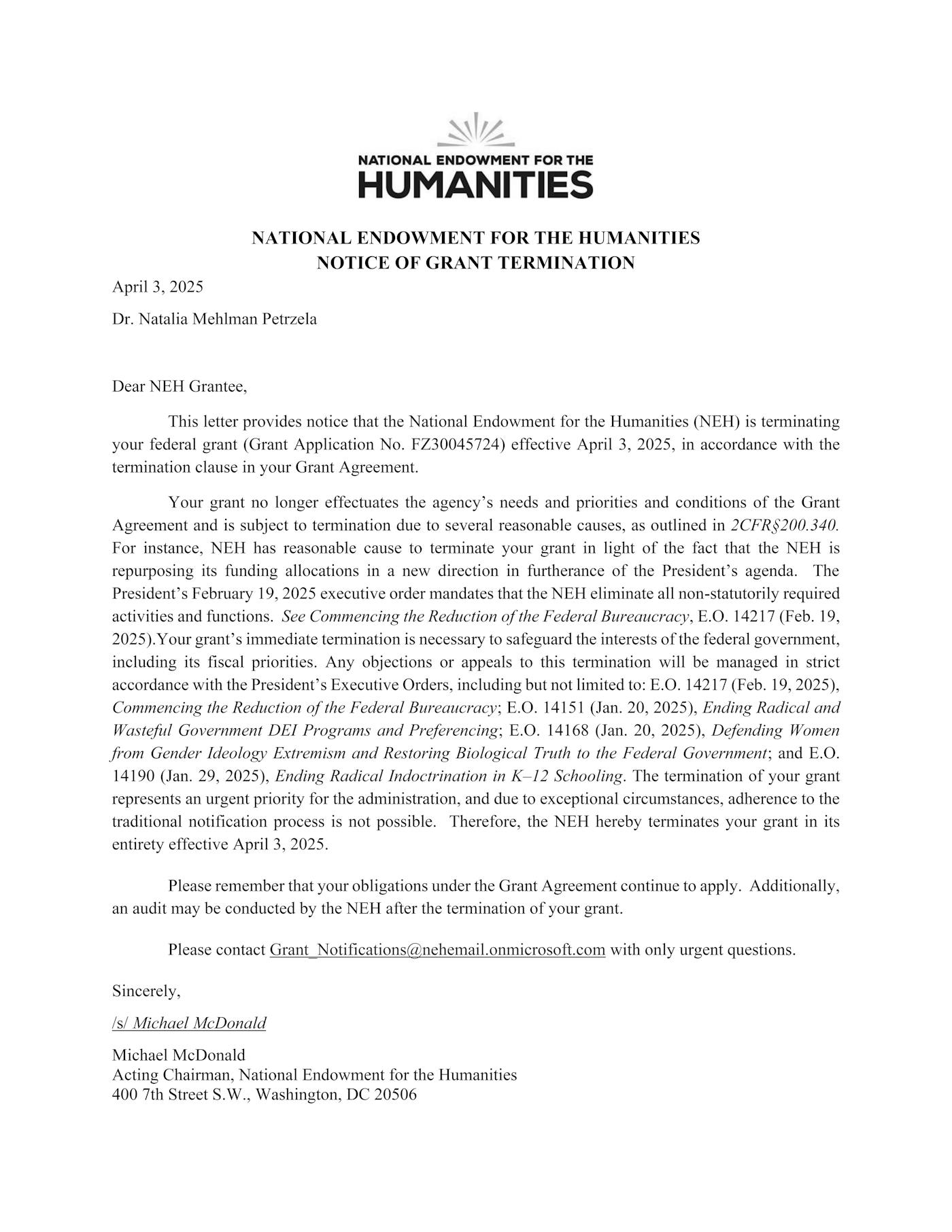

“The termination of your grant represents an urgent priority for the administration,” acting NEH head Michael McDonald, who stepped into leadership when President Trump pushed the former director to resign, explained in this letter addressed only to “NEH Grantee.” The agency is “repurposing its funding allocations in a new direction in furtherance of the President’s agenda,” and my “grant’s immediate termination is necessary to safeguard the interests of the federal government.”

While I am unsure if this termination is enforceable—the executive orders listed as rationale are not laws, after all—as a historian who spends a lot of time analyzing primary sources and government documents, I can tell you that this communication is remarkable. No proper professional courtesies, no effort to avoid the appearance of partisanship, no respect for process, no reference to the specific project at hand, not even a .gov email address: It arrived from Grant_Notifications@nehemail.onmicrosoft.com, an address so suspicious it landed in some (former) grantees’ spam folders.

You can read it yourself:

It can be tempting to wave away our current administration’s attack on education as just bluster or, on some level, as a necessary corrective to a field that has lost its way. I have never voted for a Republican in a presidential election, but I have been outspoken in raising some of the issues that galvanized Trump voters: prolonged educational disruptions and condescending sanctimony during the pandemic, a misguided obsession with ending standardized testing in the name of “equity,” and a willful ignorance of antisemitism and ideological conformity on American campuses that has been on especially horrifying display since the Hamas terror attack on October 7.

In fact, until news of my grant cancellation arrived last Thursday, I had spent most of the week working on a curricular initiative to incorporate Jewish stories into the K-12 teaching of American history and trying (unsuccessfully) to get recourse for persistent and defamatory bullying by an anonymous group of my colleagues for my speaking out against a polarizing anti-Israel resolution at my professional association. I am the first to admit that the humanities in particular and academia in general have significant issues, as I explained on NPR the day before I received notice of my grant’s termination.

Trump’s education policy, the effective shuttering of the National Endowment for the Humanities being only one example, will do little to help women, Jews, or sincere advocates of “viewpoint diversity,” all categories to which I belong. A closer look at the executive orders enumerated as the rationale for this defunding decision makes clear that Trump is escalating long-standing conservative rhetoric about “taking back” universities to a more destructive project better understood as disfiguring academia beyond recognition. Using blanket language about ending diversity, equity, and inclusion, “restoring biological truth,” and “ending radical indoctrination,” these directives are openly ideological and so broad as to encompass any individual or initiative that offends whoever in the Trump administration is calling the shots that day.

“The reduction of the federal bureaucracy” and reducing “wasteful spending” are a little more complicated. While these seem like unspectacular and even admirable goals—who denies the need for cost savings in the massive federal bureaucracy?—they strike at the heart of what the humanities, the closest thing we have to education for citizenship, are all about. Humanities research and pedagogy are by definition not driven by efficiency or instrumentalist skill instruction as their highest values. On the contrary, they are about cultivating habits of mind to assess multiple perspectives and sources to arrive at new ideas, arguments, and frameworks, all of which require time for taking, yes, inefficient, unplanned research detours and contemplating open-ended questions.

In fact, focusing too much on efficiency of research and simplicity of argument is fundamentally at odds with intellectually honest work: I warn my students that such “thesis-driven research” or “cherry-picking” historical evidence may save time, but it is inherently unsound. Thinking about the humanities as a cost center is itself a sounding of its death knell, and resisting this framing isn’t about holding fast to some nostalgic image of college students ruminating about airy philosophical concepts or mastering frivolous cocktail-party cultural literacy, untethered from everyday concerns like paying the bills. Rather, it is about protecting a rare realm in which students and faculty have the space to stop and think about what I call “the Big Questions” regarding what it means to be human.

At the risk of buying into this bean-counter mindset, I must emphasize that the NEH represents a tiny fraction of the federal budget—0.003 percent—and that the grants at stake for humanists are infinitesimal compared to the dollar amounts required by fields with large equipment and staff needs. And yet, grants like mine give scholars invaluable time away from teaching and service to engage in this kind of unbounded thinking and writing that we model for our students and our broader audiences.

Speaking of those audiences, this specific grant exists to fund “public scholars,” that is, people like me who create work widely accessible beyond the academy. Yes, like many historians, I write op-eds, but I also make podcasts, speak to groups from YMCA managers to schoolteachers, and appear regularly on the mass-market History Channel—an undertaking that directly challenges the common, and sometimes true, criticism of professors as cloistered elitists who speak only to one another in jargon.

A bunch of humanities professors losing funding is a less dramatic result of President Trump’s policies than the shuttering of a cancer research lab or, Lord knows, being unjustly thrown in a Salvadoran prison. But it is the work of humanists that is most centrally concerned with figuring out what America is, and what makes—and imperils—its yet unrealized greatness. At this precarious moment, we need more, not less, humanities research and creative production.

My grant was ostensibly terminated in service of a new focus on “patriotic programming,” but as an American and an Americanist, I am certain that resisting this dangerous decision and the broader movement of which it is a part is my civic, and patriotic, duty.