New York City’s eight million inhabitants are used to a certain amount of ambient misery. Bags of trash line the streets from time to time, although the city recently spent $1.6 million on McKinsey consultants who told them they could and should use wheeled bins instead. There are more rodents than people. They (the people, not the rodents) pay astronomical sums for rent. Aaron Rodgers briefly played quarterback for the New York Jets.

When you bring any of this up to New Yorkers, they scoff. Sure, there’s some downsides, they often say, but they live in the Big Apple! An international capital of art, culture, media, finance, sports, and the human experience! The place where Babe Ruth hit all those home runs! The place where some of the Marvel movies are set! New York City’s intrinsic and ineffable greatness, they argue, is well worth the price of everything else.

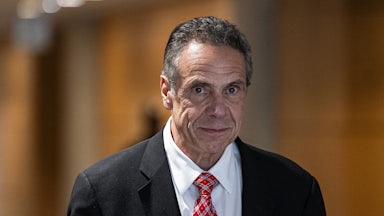

Perhaps this high tolerance for low expectations is why New Yorkers might elect Andrew Cuomo as their city’s next mayor. The city’s electorate will go to the polls on Tuesday to elect its next leader. (Well, technically, they will elect the Democratic candidate for mayor, but in the sapphire-blue Big Apple, that’s often the same thing.) Cuomo, the state’s former governor, is among the many candidates vying for the Democratic nomination and is one of two currently leading in the polls.

Eleven Democrats are running for the mayoralty this year. (Not among them is incumbent Eric Adams, who is running as an independent for reasons we’ll discuss later.) I admit that I am baffled, as a non–New Yorker, that Cuomo is not ranked eleventh in the public opinion polls of voters’ preferences. He would be the worst possible choice to lead the nation’s largest city at the worst possible time.

Cuomo governed the state of New York as an authoritarian bully for roughly a decade before his downfall in 2021. He often placed his personal interests over the public good, wielding his office like a cudgel against anyone—state and local officials, journalists, nonprofit groups—who displeased him. It is hard to see Cuomo’s campaign as anything but a cynical vehicle for his own political rehabilitation—and a second chance that one would be hard-pressed to believe wouldn’t simply continue in the self-serving ways of Cuomo’s past.

His personal enmity toward Bill de Blasio, the city’s mayor for the last half of his tenure as governor, colored every aspect of his previous interactions with the metropolis. New York media outlets often characterize the Cuomo–de Blasio relationship as a “feud,” but that does not quite capture the power imbalance. Any recounting of it at length reads more like Cuomo bullying and harassing a political and personal rival. Governors wield tremendous power over the city’s affairs; mayors can do little to change things in Albany.

In one particularly damning incident, de Blasio’s office planned to open a mass-vaccination site at Citi Field, the New York Mets ballpark in Queens in 2021 in the depths of the pandemic, only to be thwarted by Cuomo’s office, which blocked the mayor’s access to vaccines and instead opened one at Yankee Stadium in the Bronx. Cuomo’s daily pandemic updates won him praise, national airtime, and an Emmy, while de Blasio became a scapegoat by design for the city’s shortcomings as Cuomo often undermined him whenever possible.

Time and distance have told a different tale of the pandemic. It was Cuomo’s administration, for example, that moved more than 9,000 elderly Covid patients out of hospitals and sent them back to nursing homes in the pandemic doldrums of 2020. Though Cuomo’s order was aimed at relieving bed-space shortages in hospitals, it contributed to the pandemic’s deadly spread by sending infected patients into high-risk facilities. His office later tried to cover up the number of pandemic deaths at nursing homes in the state.

De Blasio has fared better in hindsight, especially after the troubled tenure of his successor, Eric Adams. (One popular article by The Onion these days features a fictional de Blasio mocking New Yorkers in graphic terms for struggling to find a better mayor.) It goes without saying that de Blasio himself is not a fan of Cuomo’s attempt at a political comeback, even comparing his politics and demeanor to another famous New York officeholder.

“I think everyone knows what I think about Andrew Cuomo in general, but I would add he’s run a fear-based campaign just like his role model Donald Trump,” de Blasio told New York magazine earlier this month. “I think more and more people are waking up to the similarities here. If you take Donald Trump’s 2024 message and Andrew Cuomo’s 2025 message, there’s so much overlap. It’s ridiculous. ‘We’re a city gripped by fear and we need a strongman to make it right,’ and he’s really not engaging the issues that are affecting everyday people, which are overwhelmingly about affordability.”

What ultimately forced Cuomo out of office in 2021 was not the pandemic or his leadership style, but allegations of sexual misconduct by nearly a dozen women. One of them, Lindsey Boylan, recounted how he kissed her without consent while she worked on the state’s economic development agency, offered to play strip poker with her on official flights, and otherwise demeaned and harassed her. The New York Attorney General’s Office identified 11 women with similar experiences in its report on the scandal; the U.S. Department of Justice concluded last year that Cuomo had run a “sexually hostile” workplace as governor.

Cuomo resigned to avoid impeachment by the state legislature and apologized for his behavior at the time. Since then, he has downplayed his actions and their seriousness. “You see all this behavior, for a 25-year-old or younger woman with different mores and sensitivities, it’s ‘Don’t touch me’ and ‘Ciao bella is offensive’ and ‘honey’ is offensive and ‘sweetheart’ is offensive, and that is a legitimate school of thought,” he told New York magazine earlier this year. “I heard that intellectually, and I got it—but I just didn’t actually get it enough.”

The former governor’s authoritarian approach went beyond his subordinates and political rivals. Last year, for example, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that Cuomo’s administration had violated the First Amendment by coercing insurance brokers into no longer working with the National Rifle Association. In one social media post that drew the court’s attention, Cuomo said that New York businesses should “consider their reputations” and “revisit any ties they have to the NRA.” He bragged about “forcing the NRA into financial jeopardy” and said the state “won’t stop until we shut them down.”

There are many New Yorkers (and many liberals elsewhere, for that matter) who wish the National Rifle Association did not exist. But it does, and wielding the power of the state to harass and destroy it purely for its political advocacy is unconstitutional. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, writing for the unanimous court, emphasized that the First Amendment “prohibits government officials from wielding their power selectively to punish or suppress speech, directly or (as alleged here) through private intermediaries.”

Cuomo’s pattern of behavior is ominous for a mayoral candidate whose campaign is fueled by score-settling. Politico spoke with an anonymous state lawmaker who described Cuomo’s recent overtures as aggrieved and retributive. “When Cuomo asked directly for an endorsement, the lawmaker said, ‘It sounded like he was on a vengeance campaign.… It didn’t sound like this was a campaign focused on working people, but revitalizing the Cuomo brand,’” the news outlet reported. “Then, after the lawmaker refused to endorse him, the threats started. Cuomo’s top aides contacted the lawmaker to suggest ‘I would live to regret my decision,’ the lawmaker said.”

It is also disturbing for a candidate whose campaign is now premised in large part on keeping the progressive left out of power. My colleague Alex Shephard recounted earlier this year how Cuomo played a central role in the creation of a state legislative bloc in the 2010s in which centrist Democrats would caucus with Republicans in the state Senate. That deprived left-leaning Democrats of the ability to pass legislation and handed more power to Cuomo, who artificially cast himself as a champion of bipartisanship.

Perhaps that is why the Democratic Party’s old centrist guard is revving itself up to put Cuomo into Gracie Mansion. Former President Bill Clinton, who appointed Cuomo to his Cabinet in the 1990s—and who is also familiar with the kind of personal scandals that dragged Cuomo from his statehouse perch—publicly endorsed the ex-governor last week. So did South Carolina Representative Jim Clyburn, who said Cuomo had the “experiences, credentials, and character” to serve as the city’s next mayor in his own endorsement shortly before Clinton’s.

The city’s wealthiest donors are also having their say. Former Mayor Michael Bloomberg donated $5 million to Fix the City, a superPAC aligned with Cuomo—so aligned, in fact, that city officials blocked him from obtaining matching funds because it said he was illegally coordinating with the group. Other donors include billionaire hedge fund manager Bill Ackman, an occasional Trump ally and an avowed opponent of diversity policies in higher education, as well as various real estate figures with a stake in the city’s housing policies.

One can hardly blame them for spending big to install Cuomo in office. New York City’s mayor is essentially a fifty-first governor, wielding more power over more people than the leaders of most states. Whoever holds the office instantly becomes a national political figure. It is unsurprising that the wealthy and well-connected want to keep out progressive candidates like Zohran Mamdani, who is currently neck-and-neck with Cuomo in the polls, or Brad Lander, who was briefly arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement last week while attempting to escort immigrants facing arrest to and from their courtroom appearances.

Looming over the election is Donald Trump. The president has worked tirelessly to exert more control over his hometown. In the first few weeks of his administration, he corruptly tried to use a federal bribery prosecution to secure the fealty of Eric Adams, the city’s current mayor. The plot failed when a federal judge dismissed the charges with prejudice, meaning that they can’t be refiled. Adams is now running for reelection as an independent but faces almost no chance of victory. Future clashes lie ahead: After Los Angeles, the White House is reportedly planning to bring its militarized immigration enforcement to other major Democratic strongholds like Chicago and New York City.

It might be tempting for New Yorkers to see Cuomo’s political maneuvering as necessary to fight Trump, especially after the supine response shown by Adams. History shows that his tactics will more likely be deployed against his personal enemies and his political foes on the left. New Yorkers already put up with a lot of hardships to live there. Electing disgraced ex-governors who are desperate for political rehabilitation does not have to be one of them.