In 2016, Charles Manson, then serving a life sentence for murdering or conspiring to murder seven people, developed a lesion on his large intestine, or possibly his colon or anus, that caused internal bleeding. The authorities, concluding that this was more than California’s Corcoran State Prison infirmary could handle, sent Manson to a private hospital in Bakersfield.

That posed no small expense to California taxpayers. Multiple uniformed state police were necessary to guard the serial killer. Manson was examined by multiple doctors, who performed a variety of tests, persuaded a reluctant Manson to undergo surgery, then changed their minds during pre-op—and not because they suddenly realized they were treating an unrepentant monster with a swastika carved onto his brow. They didn’t say, as you or I would be tempted to: “Let that son of a bitch die.” Rather, they rendered the professional judgment that Manson, then 82, was in sufficiently weak physical condition to pose an unacceptable risk of dying on the operating table. Manson died the following year after a second hospitalization.

Human beings don’t come more despicable than Manson. Yet the state of California granted him health care, free of charge. It’s something that a civilized society is called upon to do for its very worst people. Michael Moore made the same point with a comic flourish in his 2007 documentary, Sicko. Moore loaded up three boats in Miami with uninsured Americans and took them to Guantánamo Bay, where, at a detention camp situated inside America’s Navy base, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and other imprisoned 9/11 terrorists enjoyed access to an apparently well-equipped clinic. Moore shouted through a bullhorn that he wanted for his passengers the same health benefit granted the evildoers. Naturally, he was turned away.

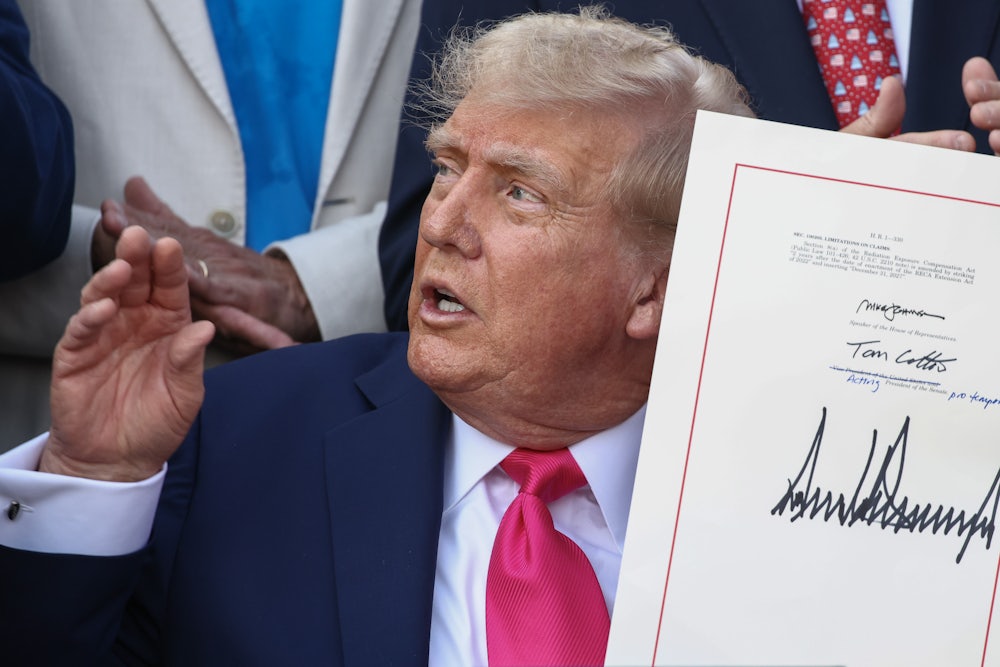

Moore’s point, and mine, is that it has never been the policy of the United States government to distribute health care on the basis of moral fitness. Last week’s signing of President Donald Trump’s “big, beautiful” budget reconciliation bill obliges me to add: “except for Medicaid.”

The budget bill boasts an estimated $1 trillion of savings over 10 years, achieved mostly by cutting Medicaid, according to the Congressional Budget Office, with the largest portion of the cuts attributable to a new work requirement. The CBO calculates that 4.8 million able-bodied people aged 19 to 64 will lose Medicaid coverage next year by refusing to work at least 80 hours per month and that another three million will lose Medicaid coverage for other reasons.

Kevin Hassett, the relentless sycophant who directs President Donald Trump’s National Economic Council, disputes CBO’s findings. He insists that “nobody’s going to lose their insurance” because Medicaid’s able-bodied malingerers will all get jobs. Trump’s agriculture secretary, Brooke Rollins, seemed to intimate Tuesday that these able-bodied Americans will replace millions of farm laborers whom the administration will deport!

Never mind that such claims contradict the GOP’s core message that the budget bill delivers significant spending cuts. Mia Ives-Rublee and Kim Mushino of the left-leaning nonprofit Center for American Progress, or CAP, counter Hassett by noting past experience with Medicaid work requirements in Arkansas and Georgia demonstrated that such requirements necessitate a lot of new paperwork to establish eligibility, and that the resultant bureaucratic mess creates a “significant loss … among eligible people and no significant change in employment.”

For the record, I side with the CBO and CAP: The Medicaid work requirement is going to throw a lot of people, including a lot of working people, off Medicaid. Because most Medicaid recipients already have jobs, whatever social problem this work requirement was supposed to address is fictitious. But as one engages with these arguments, it’s easy to forget the underlying point, which is that nobody should have to pass a moral-fitness test to receive health care. Charlie Manson didn’t; KSM didn’t. Are we seriously going to niggle over a few people guilty of nothing more than not having a job?

Such forgetting demonstrates how completely, since the 1990s, conservatives have dominated all discussion of social assistance. During the Clinton administration, Democrats conceded to a Republican Congress that, sure, all other things being equal, it was better that recipients of cash welfare take a job. (The lingering argument is about what “all other things being equal” should mean.) But the same 1996 welfare-reform law ended up imposing stringent work requirements on food stamps, where the welfare-breeds-dependency argument was less salient because food stamps could be spent only on, well, food. Previously, the unemployed possessed no acknowledged right to eat, but food stamps’ work requirement seemed to impose on them (and their children) a duty to starve. The reconciliation bill now extends that duty to a slew of previously exempt beneficiaries aged 54 to 64.

Now Congress has imposed on Medicaid recipients a duty, if God wills it, to sicken and die without medical assistance. (The Yale Budget Lab estimates the budget bill’s Medicaid and other health care cuts will kill 51,000 people.) Multiple claims by congressional Republicans to the contrary, undocumented immigrants were already denied Medicaid coverage; even legal immigrants had to wait five years before they became eligible (though 38 states have granted waivers for children and pregnant women). But the budget bill managed to carry anti-immigrant sentiment one sadistic step further by cutting state reimbursement to hospitals whose emergency rooms treat undocumented immigrants—even though these emergency rooms are required by law to take all comers. The bill also imposes additional health care restrictions on legal immigrants.

It’s a common fallacy within any meritocratic society to conclude that simply because many things are distributed according to merit (or perceived merit), everything should be. Equality of opportunity, intone the centrists, not equality of outcome. Limiting Medicaid coverage to the Deserving Poor (i.e., those who are gainfully employed) shows where such thinking can lead. People of goodwill hesitate to condemn such savagery because the United States, even when it’s governed humanely, lacks a truly universal health care system. Someday we’ll have one. But in the meantime, don’t let’s kid ourselves that we can claim to be a decent society while we dispense health care according to virtue. As those Bakersfield surgeons can explain, bad people need doctors too.