President Donald Trump followed through on his threat last week to sue The Wall Street Journal for reporting that he had sent a “bawdy” letter to Jeffrey Epstein to celebrate the financier’s 50th birthday in 2003. Epstein, who was convicted of state child-prostitution charges in 2008, died by suicide in 2019 while awaiting trial on federal sex-trafficking charges.

In their suit, Trump and his lawyers claim that the letter is “fake and nonexistent” and that the president suffered “overwhelming financial and reputational harm” from the Journal’s reporting. His complaint requested no less than $10 billion in punitive damages, a shoot-for-the-moon sum. He may as well have asked for $10 kajillion while he was at it.

The legal merits of Trump’s lawsuit are dubious, at best. The Journal is one of the most reliable news outlets in the nation, and it is extremely unlikely that it went to press without strong evidence that its reporting was accurate. As far as the legal claims go, what stands out most to me is the underlying factual dispute and the question that could resolve it: Where is the letter itself?

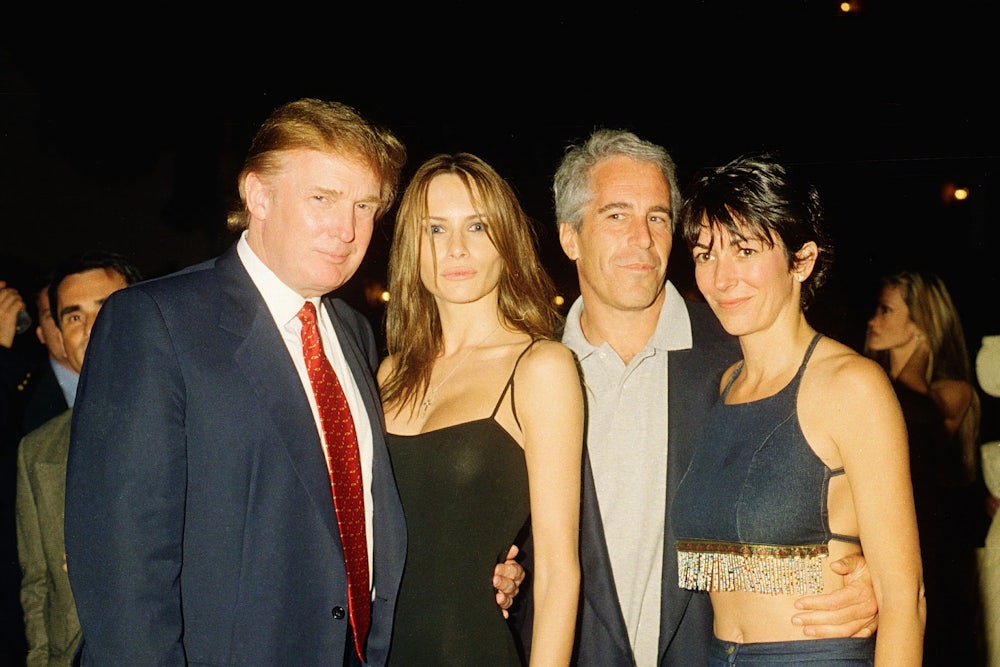

Trump’s past relationship with Epstein is receiving new scrutiny this month thanks to his own administration. Earlier this month, the Justice Department and the FBI released a joint statement claiming that their “exhaustive review” of the Epstein files found no evidence of an “incriminating client list” or other potential bombshells. Ordinarily, that would have convinced most observers. However, that statement ran counter to numerous past insinuations by Attorney General Pam Bondi and FBI Director Kash Patel that the files could contain damaging information about Trump’s political opponents.

Some of Trump’s conservative media allies, who had hyped the files’ potential release, sharply criticized the administration for its mishandling of the situation. Elon Musk, a former Trump ally looking to criticize Trump, claimed on social media that the president would be implicated by the files’ release. (Musk later partially backtracked on those assertions.) Trump lashed out at his own supporters on social media and demanded that they move on from the scandal.

The Journal’s article breathed new life into the saga by reporting new details about the depth of Trump and Epstein’s relationship. Some of the details have been publicly available for decades: Trump infamously told a magazine in 2002 that Epstein was a terrific guy and that he “likes beautiful women as much as I do, and many of them are on the younger side”—an eye-popping quote to volunteer about someone like Epstein. The president claims that he ended his friendship with Epstein a few years later and banned him from Mar-a-Lago for unexplained reasons.

“To attempt and [sic] inextricably link President Trump to Epstein, [the Journal reporters] falsely claim that the salacious language of the letter is contained within a hand-drawn naked woman, which was created with a heavy marker,” the lawsuit alleged. “Worse, Defendants Safdar and Palazzolo falsely represent as fact that President Trump drew the naked woman’s breasts and signed his name ‘Donald’ below her waist, ‘mimicking pubic hair.’” (Emphasis theirs.) The lawsuit recounted the letter’s written contents, which it described as a third-person narration of the two men’s friendship, as follows:

“Voice Over: ‘There must be more to life than having everything,’ the note began.

Donald: Yes, there is, but I won’t tell you what it is.

Jeffrey: Nor will I, since I also know what it is.

Donald: We have certain things in common, Jeffrey.

Jeffrey: Yes, we do, come to think of it.

Donald: Enigmas never age, have you noticed that?

Jeffrey: As a matter of fact, it was clear to me the last time I saw you.

Donald: A pal is a wonderful thing. Happy Birthday—and may every day be another wonderful secret.”

This is a pretty weird thing to send to a friend who would later be convicted of child prostitution by the state of Florida. “Enigmas never age” and “may every day be another wonderful secret” aren’t quite legally incriminating on their own, but they give the impression that the two men knew quite a lot about each other’s personal and romantic lives. Given what we now know about Epstein’s personal life, the letter raises questions about what Trump knew at the time—and why he didn’t tell the authorities.

Trump, both personally and through his lawyers, denied that he had anything to do with the letter. “I never wrote a picture in my life,” he told the Journal in a statement in the original article. “I don’t draw pictures of women. It’s not my language. It’s not my words.” In the lawsuit, he claimed that the reporters “concocted this story to malign President Trump’s character and integrity and deceptively portray him in a false light.”

The Journal, on the other hand, reported that it existed as part of a “leather-bound album” compiled by longtime Epstein associate Ghislaine Maxwell for Epstein’s 50th birthday, and quoted from it verbatim. The newspaper did not describe its source for the letter beyond “people who have reviewed the pages,” and its attribution for the article’s contents was “according to documents reviewed by The Wall Street Journal.”

Much of last week’s article described the album’s creation and preparation in detail. It identified the New York bookbinder who created the album—he died in 2020, making him an unlikely source—and detailed how the letters were gathered and prepared by Maxwell. It even described another letter submitted by retired Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz, one of Epstein’s former lawyers. None of this information can be found in publicly available records, so the Journal’s reporters may have relied on Justice Department documents or sources within Epstein’s circle to flesh out the album’s origins.

Why doesn’t the Journal simply publish the letter? That’s a good question. The likeliest answer is that they aren’t in possession of the original or a copy of it. The article said that the letter was “reviewed by the Journal.” It is unclear whether this means the reporters personally saw the letter itself or a photograph of the letter. The Journal described the album as “among the documents examined by Justice Department officials who investigated Epstein and Maxwell years ago,” but it is unclear where the album is currently located.

That vagueness is understandable. Reporters are ethically and professionally obligated to protect their sources, and further details about the letter’s veracity could implicate those sources. There are only so many people in the world who would have had access to the album, after all. Their source may have also conditioned access to the letter on the reporters’ agreement to not keep or publish a copy or photograph of it, perhaps fearing that it would be traceable back to them.

“Despite these unsubstantiated claims, however, the article does not attach the purported letter, does not identify the purported drawing, nor does it show any proof that President Trump has anything to do with it,” the lawsuit claimed. “Tellingly, the article does not explain whether [the Journal] obtained a copy of the letter, have seen it, have had it described to them, or any other circumstance that would otherwise lend credibility to the article. That is because the supposed letter is a fake and the defendants knew it when they chose to deliberately defame President Trump.”

Most of the lawsuit is dedicated to describing how widely the article has been shared and distributed, as if to support its claims of reputational harm. Other portions are bizarrely written. “The article was published in The Wall Street Journal as an exclusive,” it claimed. “However, since publication, Defendants have widely disseminated it to hundreds of millions of people worldwide.” Yes, that’s what publication means.

While it might seem strange that Trump would sue Rupert Murdoch—the Journal’s owner also owns Fox News and other right-wing media outlets—the media mogul has always treated the Journal differently from his other outlets. Its opinion and editorial page is easily the most conservative among major U.S. newspapers. But its newsroom journalism has generally avoided a tangible ideological drift in any direction and maintained a high level of credibility, even through the tumult of the Trump years. Among its scoops was the first revelation that Trump had paid hush money to Stormy Daniels to conceal their affair during the 2016 presidential election.

Murdoch himself has also shown far more reluctance to interfere in the Journal’s newsroom operations than with his other media properties. Elizabeth Holmes, the founder of the fraudulent blood-testing start-up Theranos, reportedly asked Murdoch in 2017 to squelch the Journal’s investigation into its lab problems. Murdoch declined, even though his own investment stake in the company reportedly totaled up to $125 million. The Journal’s coverage eventually led to Theranos’s collapse and a Pulitzer Prize.

The lawsuit was filed by Brito PLLC, a boutique law firm based outside Miami. Alejandro Brito, the firm’s eponymous founder, has represented Trump in a variety of legal battles against major media companies over the last two years. His most notable victory came last December when ABC settled a lawsuit that Brito brought on Trump’s behalf for inaccurately describing E. Jean Carroll’s sexual assault allegations against the president. As part of the settlement, the news organization donated $15 million to Trump’s presidential library and awarded Brito $1 million in attorney’s fees.

Other Brito-led lawsuits have been less successful. In 2023, for example, Trump and Brito sued CNN over its use of the term “the Big Lie” to describe Trump’s false claims about the 2020 presidential election, which he lost, as well as other remarks by the network’s contributors that compared him to Adolf Hitler and other dictators. Those remarks were obviously covered by the First Amendment, which protects Americans’ ability to describe their elected officials in blunt and unflattering terms, and a federal judge dismissed the defamation lawsuit accordingly.

Last month, Brito sent a letter on Trump’s behalf to The New York Times demanding that the newspaper retract and apologize for a June 24 article on U.S. military strikes against Iranian nuclear facilities. Trump initially claimed during a nationally televised address that the strikes were a “spectacular military success” and that Iran’s most important nuclear sites had been “totally and completely obliterated.” The Times later reported that U.S. intelligence officials had concluded that the bombings had set back Iran’s nuclear program by “only a few months.”

Brito’s letter repeated Trump’s own hyperbolic claims about the strikes, saying that they had “unequivocally eliminated Iran’s nuclear capabilities and brought peace to the region.” The lawyer also claimed that the Times, in contradicting Trump’s version of events, had “undermined the credibility and integrity of President Trump in the eyes of the public and the professional community.” (It is unclear to what the “professional community” is meant to refer.)

David McCraw, the Times’ veteran in-house counsel, wrote in a reply letter that the paper would not be retracting the article or apologizing for its contents. He noted that remarks by Trump himself and Secretary of State Marco Rubio had undercut the president’s original claims about the efficacy of the airstrikes and their impact on Iran’s regional footprint. McCraw concluded by observing that it would be “irresponsible for a president to use the threat of libel litigation to try to silence a publication” that had reported on the contradictory U.S. intelligence estimate.

If Trump is correct that the Epstein letter does not exist, that would not automatically spell doom for the Journal, at least legally speaking. The Supreme Court’s First Amendment precedents require an even higher threshold for defamation claims than mere falsity. A plaintiff like Trump must instead prove that the Journal acted with “reckless disregard for the truth”—in other words, that it did not care whether what was published was true or false, and that it intended to do harm to Trump.

That would be out of character for the Journal and its reporters, to say the least. Trump’s unequivocal insistence that the letter does not exist still raises an important question for the Journal, for the Justice Department, and for Trump himself: Where is the Epstein album, and where is Trump’s letter to him? If it is not in the Justice Department’s custody, then Bondi and Patel should explain what they know about it and its current location. And if it is in the Justice Department’s custody, then the government should release it in full as quickly as possible.