There’s an image I think about each spring when Los Angeles’s city budget cycle rolls around again. It’s a photo of about 25 LAPD officers, all clustered around two black vans in downtown L.A., waiting for something. Some of them are chatting and laughing; some are on their phones; one, hands clasped, seems almost to be meditating, though it’s hard to tell what’s going on behind those Oakleys. To mentally tabulate the overtime being accrued might provoke an aneurysm.

What exactly these officers are doing here isn’t entirely clear. They wouldn’t tell the photographer, the Dutch street documentarian Désirée van Hoek, but the gear on display offers some clues: A few of them have zip ties hanging off their belts, and riot helmets stud the tops of both vans like barnacles. So perhaps they’re prepared to quell a protest, or readying themselves for something more banal, an everyday Skid Row arrest. What they are doing here, on this particular stretch of street, is a different question, and the answer can be found at the top of the photo, where the ample canopy of a lone ficus offers relief from the noonday sun. Shade: beneficent, soothing, rare in this part of Los Angeles and rarer still if the city’s resource allocation strategies continue apace—all of which qualities put it at a point of diametric opposition to the officers who flock to it.

What decisions could have produced such an image—and what choices might we make instead? These are the sorts of questions animating the journalist Sam Bloch’s new book, Shade: The Promise of a Forgotten Natural Resource. Bloch believes that shade has been underappreciated, too often neglected in discussions of urban policy, inequality, architecture, design, and the environment. Shade is his corrective: a roving, inveterately curious account that argues convincingly for his subject’s centrality to community health, climate adaptation, and even a more robust and inclusive public sphere.

Bloch’s book grew out of an April 2019 article of the same name that initially appeared in the urban design journal Places. While the scope of the original piece stays narrowly trained on L.A., here Bloch zooms out to offer a kaleidoscopic look at shade’s past, present, and future. The book begins by a stream in Oregon’s backcountry, travels from bygone civilizations’ approach to the shadows through the history of twentieth-century American planning and design, explores the nexus of climate and inequality present in farmworker heat deaths and extreme weather events, and ends on dubious schemes to create shade on a planetary scale by injecting aerosols into the atmosphere. Over a few hundred pages, we go from Sumerian mythology and advertisements for Pompeii’s amphitheater—“there will be crucified people, a hunting spectacle, and awnings”—to tech bros’ “one weird trick that will solve climate change.”

Still, Shade’s heart is twentieth- and twenty-first-century Los Angeles, and for good reason. The city’s allure is synonymous with its cloudless weather; anyone who has ever seen the day draw to a close there can testify to the heartbreaking quality of its light. Its embrace of the personal sphere—cars clogging its arterial freeways, single-family homes sprawling out into the desert—has come at the direct expense of its communal spaces. Shade is scarce, unevenly distributed, and instrumentalized against homeless Angelenos, public-housing residents, and low-wage workers—the very people cut off from the dream of private life it promises. And all of this has left the city uniquely incapable of confronting our growing climate emergency. Like Mike Davis before him, Bloch shows us the dark side of a city indelibly associated with sun.

Returning to the United States in 1939 after a decade abroad in France and Greece, the writer Henry Miller found himself disgusted by what awaited him upon docking: Boston, Massachusetts. “I was praying that by some miracle the captain would decide to alter his course and return to Piraeus,” he recalled. (His hometown proved no better: “I felt as I had always felt about New York: that it is the most horrible place on God’s earth.”) For years, Miller roved the country, recording his thoughts. “Nowhere else in the world is the divorce between man and nature so complete,” he wrote.

Miller had a talent for titles, and the name he chose for his memoir of the United States is succinct and brutal: “The Air-Conditioned Nightmare.” Bloch borrows the phrase and takes a similar, if less hyperbolic, tack in Shade’s first section, detailing how the United States began to turn away from natural cooling at the dawn of the twentieth century. Americans living in cities had always relied on open windows, awnings, fans, and blinds to stay cool. They made use of the natural environment, sitting out on the stoop in the evenings with their neighbors or even sleeping in the park or on fire escapes when it got too hot.

But this old way of living began to conflict with a new trend in American life: sun worship. Progressive reformers embraced sunlight as a natural disinfectant. The modernists extolled the virtues of glass—Le Corbusier called it the “fundamental material of modern architecture.” Urban planners used the brand-new concept of zoning to prioritize single-family homes (sunny, spacious) above tenement housing (dark, damp, potentially pestilent) and establish height restrictions on buildings to avoid casting the city streets in shadow. And the Federal Housing Administration’s design standards applied those same values to the nascent suburbs en masse. All of this was made possible by AC, which also fueled the mass migration of Americans into parched desert outposts where so many humans should not by rights exist. (One wonders what Miller would have made of modern-day Phoenix.)

As Bloch explains it, there are two big trends here that would come to define postwar America: a retreat from the commons, and an embrace of manufactured, resource-intensive comfort at any cost. America on AC is an America suspicious of strangers and the outdoors, intolerant of discomfort, addicted to the lonely monotony of suburbia, and willing to sacrifice a great deal to avoid addressing these pathologies—more nightmare than dream. And artificial cooling, of course, only addresses a symptom; in doing so, it worsens the disease. Today, Bloch notes, Americans expend more energy on climate control than the entire continent of Africa uses on anything: “It’s not an overstatement to say the pollution we generate for cooling is burning the planet.”

Where better to understand the ramifications of our turn away from shade than the city arguably most hostile to it? When Bloch lived in L.A., he was shocked by how deserted this ostensibly teeming metropolis can seem. “There was no one around,” he told the podcast 99% Invisible. The people who were around were waiting for buses behind telephone poles or even standing in each other’s shadows—anything for a meager helping of shade.

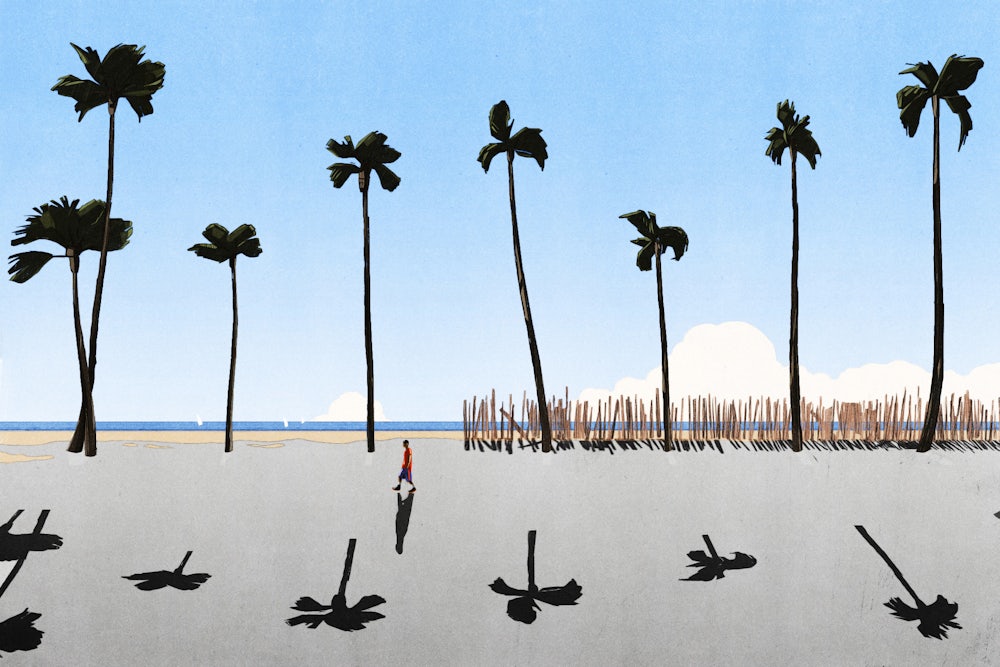

In L.A., Bloch realized, shade has become a luxury. Flying into Los Angeles, you can see just how starkly tree cover correlates with race and socioeconomic status. On the approach to LAX, you confront the endless asphalt grid of South L.A.: streets, bungalows, palm tree after spindly palm tree. In the distance, the verdant hills of Los Feliz and Silver Lake beckon. (Bloch’s bio for his Places article mentions that he resided in one of the city’s “shadiest neighborhoods,” which comes off as kind of a strange flex, given his thesis.) It turns out the disparity is detectable from even farther away than that: “You can see L.A.’s shady divide from outer space,” he writes.

One big reason for the city’s patchy tree canopy, of course, is natural resource limitations—water, in other words. During his chapter on “La Sombrita,” a bus stop shade pilot program so underwhelming it went viral, Bloch compares Los Angeles to Singapore, a city that he acknowledges has a tropical climate. Yes, there are policy differences—Singapore benefits from top-down urban planning, owing to its semi-authoritarian government—but the real difference between the two cities, one suspects, is that one of them has buckets of rain falling from the sky for roughly 170 days a year. As L.A.’s leafiest neighborhoods attest, greenery can flourish when properly tended. In wealthy areas, Bloch notes, this mantle is taken up by private citizens—residents with time and money to spend.

There is also the city’s long history of racist urban design: the restrictive covenants that forced Black residents into comparatively denuded areas to begin with, and the freeways that the city carved into those communities in the 1960s. Any way you slice it, this imbalance leaves the city’s lower-income, Black and Latino neighborhoods far more vulnerable to the grim effects of urban heat. Bloch introduces readers to Debbie Stephens-Browder, a former schoolteacher from Compton who later worked with a local organization dedicated to planting trees in the community. For Stephens-Browder, who became homeless in 2017, this was not the idle pastime of a retiree but a matter of life and death: Unhoused people account for over 40 percent of heat fatalities in L.A.

At this point it’s sort of a truism, albeit a worthy one, that climate change falls hardest on the people least responsible for it and most defenseless against it. Bloch makes a more interesting intervention—he shows how the city’s terrorism toward its disfavored groups also accelerates warming, in addition to producing a generalized degradation of public space.

Guided by theories like the architect Oscar Newman’s “crime prevention through urban design,” LAPD’s reliance on aerial surveillance and security cameras has spawned endless requests for tree pruning—and since the city lacks the funding to do regular maintenance, it often opts to remove those trees entirely. During the pandemic, cops and city council members told housed residents frustrated by encampments on their blocks to “take away the comfort level” by trimming foliage to reduce shade. “This will at least force them to look for another place,” one officer wrote, neatly, if unintentionally, summarizing Los Angeles’s general approach to homelessness. Bloch frames this weaponization of shade as a form of hostile architecture, “no different from removing a bus bench so no one can sit there, or throwing boulders on sidewalks so no one can hang out there.”

It’s not as though L.A.’s leaders haven’t noticed that their city has a shade problem: The last three mayors have tried to put in more trees—in 2019, Mayor Eric Garcetti debuted a city-specific Green New Deal, which included a scheme to plant 90,000 by 2021, saying, “this is the fight of our lives.” But there are a lot of bureaucratic barriers to changing anything, Bloch explains, and the city seems to lack the political will to realize its big ideas. Despite his bellicose rhetoric back in 2019, Garcetti left office at the end of 2022 not having gotten anywhere near his goal. And even good-faith efforts are undermined by the city’s relentless war of attrition against its poorest and most marginalized residents. What use is planting a sapling that won’t provide meaningful shade for years when existing trees are being removed in order to chase homeless people down the block?

When tough times hit, trees tend to be the first things to go. This year, Mayor Karen Bass’s proposed budget included zero funds for new planting and significantly less money allocated toward maintaining the city’s existing tree canopy. The budget proposal was a study in austerity, in almost every respect but one: It lavished ever more money on the LAPD. If the city stays on course, there will be more officers and less shade—for them, or for protesters taking to the streets to voice their dissent and defend their neighbors from ICE, the unhoused people who sleep on the barren sidewalks of Skid Row, the street vendors who ply their wares there, the cleaning ladies who wait for the bus, or anybody else.

Like many young writers on the left with an interest in California, Bloch is clearly a disciple of Mike Davis, whom he interviewed and quoted at length for his initial article. The late historian appears in Shade, too, though his presence is more gently pervasive than explicit. Even the chapters that aren’t about L.A. betray his influence. For instance, Bloch’s take on our turn away from natural cooling, and the brief window when architects realized which way the air was blowing and tried to do things differently, is classic Davis: glimmers of an alternate future, foreclosed upon. (“We could have embraced shade,” he writes. “Instead, we doubled down on AC.”)

In many ways, Shade reads as an homage to “The Case for Letting Malibu Burn,” Davis’s classic essay on L.A.’s disparate response to two types of blazes: the infernos that engulf neglected tenements in Westlake and the inevitable wildfires that threaten its moneyed canyons. Amusingly, each writer’s choice of focus is reflected in their style. As with Henry Miller, Davis’s tone is often one of holy zeal; his argument in “Letting Malibu Burn” is incendiary in more ways than one. Bloch, meanwhile, stays cool: measured, given to reconsideration, fond of constructions hedged with “perhaps” and “maybe.” He clearly feels strongly about the inequality he portrays, but his tone is so evenhanded that it can belie the urgency that would seem to follow from his diagnoses. The last third of the book is devoted to a series of shady interventions that range along a spectrum from adapting to our environment to trying to modify it, and the solutions that Bloch ultimately expounds are all eminently reasonable.

The La Sombrita debacle provides an occasion to explore various global cities that have adapted their physical layout for maximal shade rather than trying to MacGyver it into the existing built environment, as L.A. has done. Barcelona, Bloch writes, has reconstructed its urban zone to install traffic-free “superblocks,” created an ingenious irrigation system to ensure that its street trees stay hydrated, and collapsed various agencies that deal with transit and city planning into a single entity to avoid the sort of bureaucratic stumbling blocks that doom such innovation in Los Angeles. Sun-drenched Australia, meanwhile, has embarked on a robust public health campaign to educate residents about the dangers of solar exposure, which one research scientist compares to America’s successful imposition of a tobacco taboo during the second half of the twentieth century.

Meanwhile, the most technically radical idea proffered here, geoengineering, reads as wildly unserious and possibly nuclear-level dangerous. (Some choice quotes from the chapter protagonist’s contretemps with the federal government: “This vaguely DARPA-affiliated motherfucker is like, ‘You should worry about your safety if you keep launching there’”; “I’m going to get shot by, like, federales over launching weather balloons?”) One advocate warns that someone like Elon Musk could latch on to the idea and “meaningfully change the global climate without scientific oversight or democratic control.” Please, don’t give him any ideas.

Bloch’s ultimate assertion is that embracing shade can and should be done by degrees and with precise but realistic, low-tech interventions. He offers practical, even technocratic policy recommendations for L.A.: “combining the public works and transportation departments into a single infrastructure agency,” coming up with a capital infrastructure plan that prioritizes shade. Paradoxically, he argues, the only way to actually get to a place of radical change is to embark now on this sort of sustained, unsexy municipal reordering—no guillotines needed.

But can it happen here? The thrust of the La Sombrita chapter is roughly that the United States should become more like Europe or Australia. Bloch quotes an architectural historian who proposes a life “after comfort”: learning to live with the heat rather than resist it. The thought of Americans voluntarily downgrading our standard of living—giving up our everyday use of AC—seems well-nigh impossible. It would lead to other sacrifices, too. One does wonder just how much water goes toward maintaining the private oases of Brentwood and Windsor Square that Bloch describes; meaningful climate adaptation might also leave L.A. looking a little more uniformly parched.

Part of the issue is that Bloch tends to toggle between Los Angeles and the country writ large, as though the two were synonyms. While L.A. is a terrific metaphor for the American problem, policy is granular and particular, and this collapse risks giving the impression that the United States is uniformly bad on shade. But there is no natural—or national—law dictating that poor people live in neighborhoods with less tree cover. As Bloch demonstrates so persuasively elsewhere, the shape and feel of our lives in cities are results of concerted choices. Earlier in the book, he cites a fascinating study showing that public housing in Brooklyn, Harlem, and the Bronx actually boasts more tree cover than their surrounding neighborhoods, leaving average temperatures lower in the projects. More examination of cases where U.S. cities have made different choices might have sustained the nuance of his earlier chapters and helped prove that it is possible, even here, to make urban planning decisions that reduce inequality rather than exacerbate it, that meaningfully and visibly improve the quality of life.

And if we choose not to—well, at some point the choice will be made for us. Whenever that happens, we might belatedly discover the virtues of shade. Unlike AC, it will still be there, offering some possibility of relief.