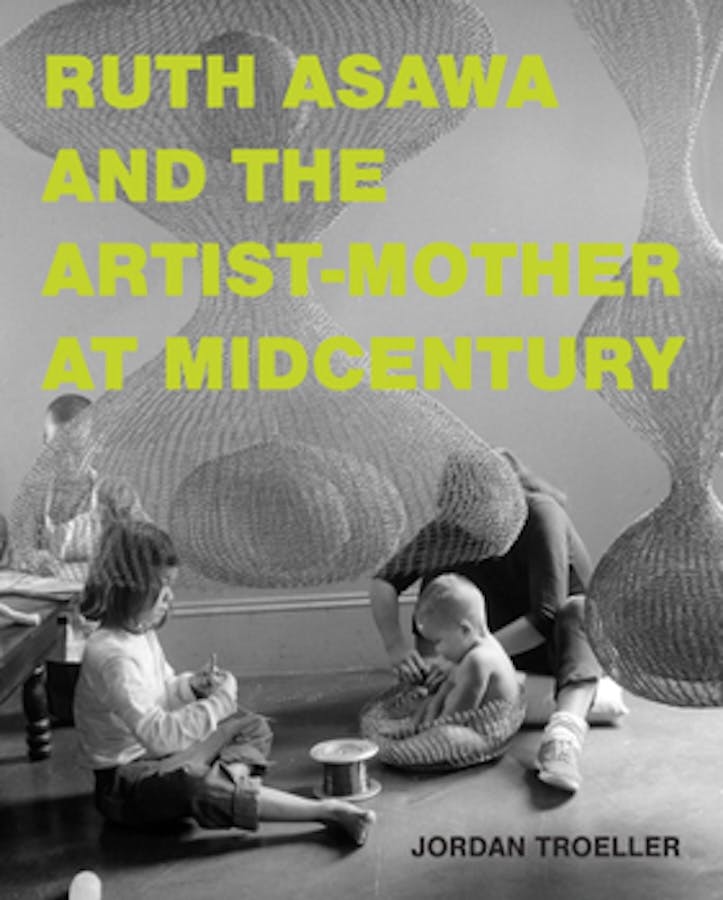

A photograph of the artist Ruth Asawa and four of her six children, taken at her home by Imogen Cunningham in 1957, shows a scene of working life. In the foreground are Asawa’s hanging multilobed sculptures; Asawa, wearing old tennis shoes and stretched-out socks, her face obscured by her sculpture, is making a looped-wire basket around a baby who has improbably just crawled into it; nearby, a daughter dutifully loops wire onto a dowel, while two boys, one wearing an apron, sit peacefully in the background. One possible interpretation: a feminist art fantasy, home and work brought together at last. Another: an artist among her many creations. Another: a mother, trying against all odds to make her art. Another, jealous: How on Earth did she manage it? Another, cautionary: This is what you have to be able to do to have both.

It’s a remarkable image, and trying to sort your feelings about it can show how vexed motherhood has been and still is for so many women artists—the “awful dichotomy,” as the painter Alice Neel called it, between art-making and caretaking. But Asawa wanted six children, and she also wanted to be an artist. It is testament to her character that she refused to see these desires as incompatible, despite a modern art establishment that largely agreed with Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Albert Ten Eyck Gardner when he wrote in 1948 that “the greatest contribution to the world of art that could be made by a woman was to be the mother of a genius.”

Can you be a real artist and a good mother? There are as many answers to the question as there are artists who can become pregnant. In an energizing and brilliant new monograph, Ruth Asawa and the Artist-Mother at Midcentury, art historian Jordan Troeller figures Asawa as the center of a community of San Francisco “artist-mothers,” a figure whose example offers a powerful correction to the history of modern art. The artist-mother is not a lone artist endeavoring to perfect a finished work but an artist working within a community, devoted to art-making as an ongoing process, a gift to the future rather than an argument with the past.

“Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective” at the Museum of Modern Art, following its opening at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, is the latest in a cascade of shows since her death at the age of 87 in 2013, and is remarkable for conveying the breadth of Asawa’s art practice—how it overlapped with family and with community, how it emerged from the broken rhythms of daily life, how it was powered by a lifelong fascination with form. While her wire sculptures and her civic fountains are her best-known works, Asawa drew daily, painted, made lithographs, shaped clay. She rarely gave any of her works titles, more interested, it seems, in the constant process of creation than in final work. She helped found one of the most vibrant public school arts programs in the country and was the force behind the establishment of the San Francisco School of the Arts, a public high school. She and her husband, the architect Albert Lanier, raised their children in a house full of art-being-made. The doors at her home in San Francisco’s Noe Valley were rarely locked: Her son Paul remembers, “People would just walk in.”

Formed out of the swirl of daily life, the resulting works have all the beauty of objects with a life of their own. Her sculptures seem to breathe. Her hanging looped-wire forms, rounded and organic as gourds, fluted as seashells, turn slowly as you watch them. They move out of the corner of the eye, and you wonder if they will grow a new lobe while you stand there, a fruiting body. Like all living things, they seem to need space, company, and sunlight.

One of the many wonderful things about this thoughtfully curated show is that it captures the feeling of a growing thing: You enter the show not in a big bravura act but sideways, through a kind of antechamber of the artist’s early works. The first thing you see is quiet: an early looped-wire basket, self-satisfied as a sea urchin. The art in these first rooms can feel jumbled, too many small pieces rattling around in a too-big space. But turn around, and there it is: a big skylighted room with only Asawa’s hanging sculptures, an elegant and hushed cathedral.

Asawa’s work refused many of the binaries of the art world of her day, and critics tied themselves in knots trying to define her. Was her sculpture fine art, or was it decorative crafting? Why was she making figurative work—the fornicating frogs and breastfeeding mermaids of her Andrea fountain in San Francisco’s Ghirardelli Square—when she was known as a minimalist, abstract artist? Neither did her life fit a set of either-or questions: Was she Japanese or American? An artist or a mother first? Wasn’t fine art meant to be a stratum above ordinary life?

Asawa’s parents were truck farmers in Norwalk, California, supplying vegetables to the farmers market in Los Angeles. Her father, Umakichi Asawa, arrived in the United States from Japan at 19; her mother, Haru Yasuda, was a picture bride. Ruth (called Aiko at home) was born in 1926. Haru carried her on her back as she worked in the fields, as she did with each of her seven children. Unable to own property due to California’s anti-Japanese Alien Land Law of 1913, the family leased 80 acres, and through hard work and quite a bit of discipline, they made a living.

Ruth, the bold middle child, was sure, at 10 years old, that she wanted to be an artist. She took the wires for bunching vegetables and twisted them into jewelry, she won art contests at school, she traced undulating designs in the dirt with her toes. On Saturdays, the Asawa children went to gakuen, the Japanese school, where Ruth dozed during language lessons but thrilled to Japanese calligraphy, with its emphasis on precision and restraint, its balance between the ink on the page and the weight of blank space around it.

On December 8, 1941, the day after Imperial Japan attacked the Pearl Harbor naval base in Hawaii, the principal of Ruth’s high school urged the student body to keep calm. It is a shame no politician listened to him, as long-standing “yellow peril” fears of Asians as a disloyal element within the country curdled into hysterical racial hatred and government policy. “Prohibited” and “restricted” zones were declared, limiting Japanese Americans’ movement across the West Coast, followed by a curfew for so-called enemy aliens. Racial identity and national belonging was the first dichotomy imposed on Asawa; as curator and specialist in Asian American art Karin Higa wrote in 2007, Asawa’s ancestry made her both “inside and outside at the same time.”

Umakichi dug a hole outside the house and burned anything overtly Japanese, including books on the arts of the tea ceremony and flower arrangement. “Oh, please don’t, don’t burn the books,” Ruth’s sister Lois pleaded in tears. But no matter: One day in February 1942, just before lunchtime, two FBI agents came to the farm and walked out into the fields where Umakichi was tending to his strawberries. They took him away, and Ruth did not see him again until after the war.

Two months after Umakichi’s arrest, wide-scale evacuation orders were given to all Japanese Americans up and down the West Coast. The Asawas left with what they could carry for the Assembly Center at Santa Anita racetrack, where they were housed in a hastily whitewashed horse stable.

Of internment, Ruth remembered later, “the arts saved us.” For the first time in her life, she found herself among a dense community of Japanese American artists who set up a de facto art studio and school in the racetrack grandstands. Internment had brought together bohemian painters from the Art Students League of Los Angeles and staff animators for Disney Studios, including Tom Okamoto, who gave the eager Asawa her first formal lessons in painting and drawing.

After five months, the Asawas were sent to one of the 10 concentration camps, as they were called at the time, in desolate regions of the country. The Asawas landed in the swamps of Rohwer, Arkansas, guarded, like all the camps, with barbed wire. Sentries in the guard towers pointed their guns inward toward the prisoners.

Internment perhaps gave Asawa her first, traumatic lesson in sculpture, as there is nothing like prison to accentuate the movement of bodies in space. As Anne Anlin Cheng proposes in a tensile, perceptive essay in the current show’s catalog, Asawa’s art explores “what it means to live as an object.” Her most famous sculptures, Cheng points out, rework the wire that once held her family, looped and tied into organic forms that welcome movement, rather than forbid it.

After she graduated high school at Rohwer in 1943, Asawa hoped to become an art teacher and received clearance to leave the camp for Milwaukee State Teachers College, suitably cheap and located outside of the designated evacuation zone. But she was prevented from graduating, as no classroom would accept a Japanese American student teacher—and on the advice of a friend, Ruth applied to the new, experimental Black Mountain College in North Carolina. The decision changed her life.

Black Mountain College, founded as a progressive education project in 1933, was almost single-handedly responsible for the American midcentury avant-garde. The faculty were European refugees fleeing Nazi Europe and innovative American modernists; the students an interracial, coed, energetic postwar generation. In the summer of 1948, during Asawa’s stay, the faculty included John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Willem de Kooning, Josef Albers, Anni Albers, and Buckminster Fuller. One of Asawa’s fellow students was Robert Rauschenberg. It was a magic time: You can almost hear the air crackling.

The ethos of Black Mountain was to educate “the whole person—head, heart, and hand.” Students learned to make art; they were also taught what it might mean to live as an artist. Accordingly, students were not graded, socialized with the faculty, and took part in school governance and the hard labor of maintaining the school itself: farmwork, laundry, kitchen duties, building repairs.

Asawa thrived: No longer did she want to be an art teacher, but an artist. She was encouraged to question and be disloyal, rather than obedient—a tonic, perhaps, for the “loyalty oath” the U.S. government had demanded all Japanese Americans take during the war. She studied dance with Merce Cunningham and architecture and industrial design with Buckminster Fuller; she gave haircuts and churned butter in the campus dairy and worked in the laundry. Most importantly, she studied design, color, drawing, and painting with Josef Albers.

Albers and his wife, the textile artist Anni Albers, had fled Nazi Germany when the famous Bauhaus school was closed by the regime, and brought the democratic ethos of German modernism to America. He taught craftsmanship, not craft—a way of seeing, not the ability to make a skilled reproduction. His central lesson, as Asawa later recalled, was “never to see anything in isolation.”

Asawa took to the school’s emphasis on making studies rather than finished works, a habit of working that never left her. She created spiraling sunbursts and undulating curtains of ink with the “BMC” stamp from the college laundry; she painted an abstracted dancer, with arms in fifth position, in numerous color variations. During a trip to Mexico, she learned a technique of looping wire for basket-making and, back at Black Mountain, began to experiment with creating small baskets and hanging lobed sculptures.

Art, Black Mountain had taught her, was inseparable from life, and Asawa meant never to put the two in competition. She had fallen in love with Albert Lanier, an architecture student from Georgia, and they decided to create an art-life together dedicated to “the beautiful and the difficult.” Their letters reveal an enviable and rare partnership: “I will take no more love from you until you have given your own work the love it deserves,” Asawa wrote Lanier in December 1948, just before they set out together for San Francisco.

The couple moved into a rented loft above an onion warehouse in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Lanier joined a local architecture firm, and Asawa turned their home into her studio, working most of every day. It was in that loft that Asawa married Lanier in 1949, wearing a black skirt suit made of fabric designed by Anni Albers. Buckminster Fuller designed Asawa’s ring, using a smooth black river stone in place of a gem. The reception was at a friend’s house in Sausalito, where there were cold cuts and champagne and views of San Francisco Bay. Then it was back to their rented loft with the leftover champagne, and back to work.

The couple had four children and adopted two, requiring them to move four times to find a house large enough to fit everybody. Motherhood would profoundly inform the way Asawa worked. As she herself explained it, “Because I had the children, I chose to have my studio in my home. I wanted them to understand my work and learn how to work.” Accordingly, Asawa chose to work with nontoxic materials, using repetitive techniques—like looping wire—that could be interrupted and easily picked up again. It helped that she was a lifelong insomniac, normally sleeping only four hours a night, fearful of sleeping too much and “losing the opportunity to create.”

Art and life, art and parenting, were inextricable, folding in and out of each other like one of Asawa’s Möbius-like sculptures. At the Asawa-Laniers’ house, dinner was prepared on the same counter where baker’s clay was expertly mixed by young daughter Addie and sculpted into Asawa’s fountains for San Francisco’s public squares. Asawa’s work spilled out into the whole house, and indeed she and Albert intended it to: In their first home, Asawa’s studio was on the main floor, and even when they had moved to a larger house in nearby Noe Valley and Albert excavated a basement to construct her first dedicated studio, her work, in the words of a friend, “often takes over the whole house.”

At the middle hinge point of the MoMA show, there is a dark-walled room “inspired” by “the artist’s home and studio” holding intimate effects—Asawa’s wedding ring, the large wooden doors to the family home, which Asawa and her children carved into an ocean of swirled ridges with chisels. There’s even a photocopy of one of her hands, creased and wrapped in tape to protect it from wire cuts. As is captured beautifully by Janet Bishop in an essay in the lush accompanying catalog, this is art that belongs with a life, not art for museum vitrines. There is a distinct poignancy to seeing it here, for the loneliness of the artifacts tells you, like negative space, how fully part of a family’s life Ruth Asawa’s art must have been.

Unlike her contemporary Louise Bourgeois, whose work often explicitly depicted motherhood as a bodily passion play, Asawa rarely made motherhood the subject of her work. Rather, motherhood was its amniotic fluid: As curator Helen Molesworth has memorably put it, her lobed sculptures, with their forms-within-forms, connected and continuous, have a “fetal energy.”

As Troeller discusses at great length, Asawa devoted much of her time not to making art about mothering, but to scaling up her artist-mothering to citywide level—what Troeller calls “caretaking in public.” Asawa, along with her friends, neighbors, and fellow artist-mothers Andrea Jepson, Sharon Litzky, and Sally Woodbridge, proposed, organized, and secured funding for the nation’s first artist-led curriculum in a public school system, the Alvarado School Arts Workshop. The pilot program began in 1968, and a decade later, the National Endowment for the Arts recognized it as the most vital arts program in the country, operating at 80 percent of San Francisco’s public schools. Artists led children in creating mosaics, sculptures, textiles, and gardens to brighten their own schoolyards. Asawa had her old friend Buckminster Fuller stop by to make geometrical sculptures out of plastic straws.

The current show offers a bright side gallery, set up like a classroom, honoring this aspect of Asawa’s work and recognizing it as art work in its own right. This is the most archival of the galleries, and its charm is quiet—a photocopied guide to creating milk carton sculptures, a typewritten page of children’s answers to the question, “What do you think it means to be an artist?” Lest you worry that this is just an homage to the lost years of national arts funding, the gallery holds 12 colorful bas-relief murals made in painted baker’s clay from public schools across New York’s five boroughs, created this year by schoolchildren under the direction of a working artist. Our city, in their eyes, is bright and blue-skied, full of rats and pizza, rainbows and trees and children.

Their way of seeing is also hers. Asawa’s art work was a continuous and looping thread of creation and cultivation at the personal, familial, and citywide levels. She raised, and taught, children who were not biologically her own, and so we might consider artist-mothering not as a gendered activity, nor a biological one—nor even one requiring the presence of a child—but rather, an ethos of world-creation, cultivation, and connection, available to us all.

“Everything is connected, continuous,” Asawa once said of her looped-wire sculptures, and that means they are also infinite. Things are never self-contained, her work says. All things create more things: more relationships, new possibilities, another beginning. This is how the world goes on.

“Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective” is on view at the Museum of Modern Art through February 7, 2026.