In 1957, as Cold War paranoia gripped the world, African Americans trudged toward greater freedoms. That year, Martin Luther King Jr. and his comrades founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and launched a major campaign to register disenfranchised voters. Congress strengthened the federal government’s ability to protect civil rights, and a group of nine Black boys and girls successfully integrated Little Rock Central High School. The civil rights movement—defined by boycotts, large-scale demonstrations, and strategic local organizing—was well underway and yielding promising results.

Halfway across the world, a similarly progressive energy permeated the air. On the night of March 5, 1957, minutes to midnight, Kwame Nkrumah, then prime minister of the Gold Coast and soon to be first prime minister of the independent nation of Ghana, stood before a buzzing crowd. “At long last the battle has ended,” he declared to the tens of thousands present, “and thus Ghana, your beloved country is free forever.” Not only did this momentous occasion mark a dramatic shift in the nascent country’s development, but it also signaled a new era for other colonial entities. Capitalizing on the crowd’s enthusiasm and undivided attention, Nkrumah reminded his audience that Ghana’s singular “independence is meaningless unless it is linked up with the total liberation of the African continent.” The world was on the cusp of change, and the only way to ensure Africa’s place in it was to embrace Pan-Africanism.

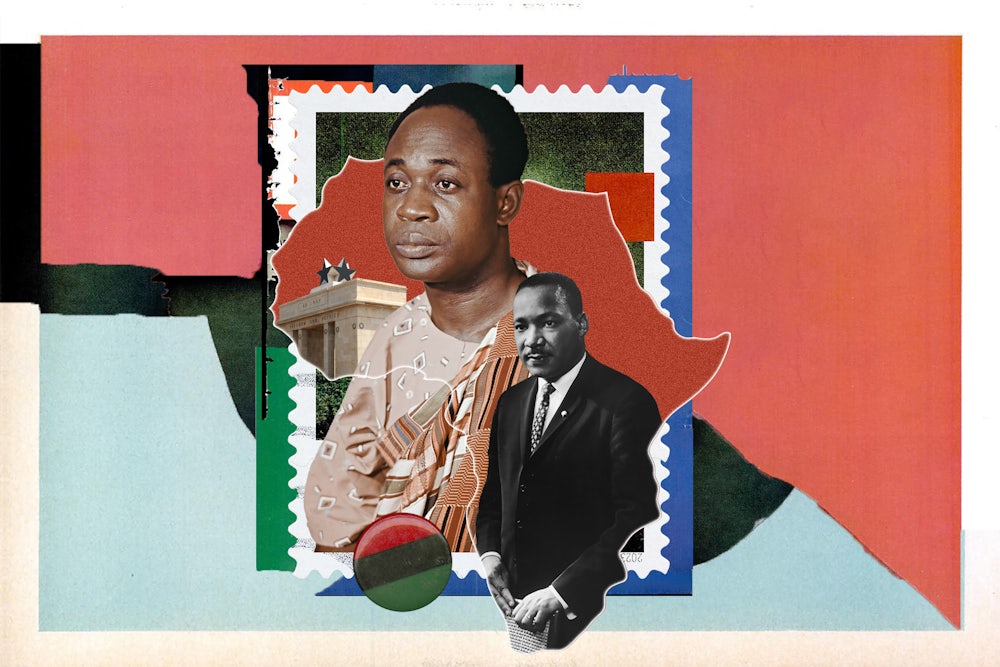

In his captivating new book, The Second Emancipation: Nkrumah, Pan-Africanism, and Global Blackness at High Tide, the journalist and scholar Howard W. French recasts the story of the post–World War II global order as a Black liberation epic instead of a psychodrama between Washington and Moscow. His chief characters are not Kennedy and Khrushchev but rather Nkrumah, his fellow postcolonial leaders, and Black intellectuals and organizers in the United States. French considers the dawn of the Cold War alongside the development of Pan-Africanism, a movement committed to the self-determination of African nations and political unity between Black people across the diaspora.

He also examines how global efforts to end fascism in Europe fundamentally altered the consciousness of conscripted African and African American troops now caught in a peculiar twentieth-century contradiction. How could Black people in the United States be asked to fight on behalf of a country built on their disenfranchisement? Similar questions arose on the continent, as European colonial powers extracted from their subjects through military drafts, underpaid labor, and theft of natural resources. The blatant exploitation ignited a period of intense organizing in the United States, Africa, and the Caribbean, portending a decade of domestic civil rights advancements and successful decolonization movements. French proposes that this period—which he calls a “second emancipation”—marked the true end of slavery, and that its emerging Pan-Africanist theories offered a path for free nations to “fend for themselves in a world dominated by imposing powers.”

The Second Emancipation arrives at an energizing time for contemporary Pan-Africanist thinking. It joins a recent slate of works resuscitating conversations about the movement’s political history, cultural present, and practical future. Last year, critics celebrated the Belgian filmmaker Johan Grimonprez’s Oscar-nominated documentary Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat, which investigates how the United States deployed jazz “ambassadors” like Louis Armstrong to Africa to distract from its covert operations on the continent. Grimonprez not only reexamines Belgian and U.S. complicity in the harrowing assassination of the Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba; he also draws connections between the struggles of African revolutionaries and anti-imperialist Black organizers in the United States. Soon after Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat landed in theaters, “Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica” opened at the Art Institute of Chicago. The exhibition, which has now closed, surveyed the cultural history of Pan-Africanism, from material propaganda to artists inspired by the movement’s ideas. Both “Project a Black Planet” and Soundtrack gestured to Pan-Africanism’s contemporary manifestations and utility for movement work.

French, a longtime journalist and author, most recently, of Born in Blackness, a crucial text that reaffirmed the important role sub-Saharan Africa played in the development of modern civilization, takes a similarly forward-looking approach. He challenges lazy theories that attribute Africa’s current economic precarity and political instability to incompetence and wonders what the continent might look like if today’s intellectuals and organizers readopted Nkrumah’s Pan-African ideals. What could Africa—and the broader Black diaspora—achieve if her people focused on building material connections across national and ethnic identities? These questions frame French’s biography of Nkrumah, which blends rigorous archival research, vivid on-the-ground reporting, and poignant personal anecdotes to construct an admiring portrait of Ghana’s first leader. While French never shies away from Nkrumah’s flaws, he remains a sympathetic biographer, acknowledging the pressures the Pan-Africanist faced and the antagonistic forces abetting his eventual downfall. Although The Second Emancipation aims to be a wide-ranging survey of a singular revolutionary moment, it is most persuasive and propulsive when French homes in on Nkrumah’s almost mythic journey from a village son to a nation’s hope. The Ghanaian leader’s story is an opportunity to reconsider Africa’s current destiny.

There are few details available about Nkrumah’s origins outside of his own writing, which French relies on in the early chapters of The Second Emancipation. Nkrumah was born in the Nzima village of Nkroful as Francis Nwia Kofi Nkrumah, to parents of modest means. His mother, Elizabeth Nyaniba, wanted her son to succeed, so when Nkrumah was young, she moved to a larger town and enrolled him in a Roman Catholic mission school. Although Nkrumah disliked the experience—he ran away on his first day—it opened doors that led the way toward his brilliant future. There’s an apocryphal sheen to parts of Nkrumah’s biography, which can be attributed to the political leader’s propensity for self-invention and the messianic role he would eventually play in Ghanaian history. After roughly eight years of school, Nkrumah entered the newly formed Achimota College, where he studied to become a teacher. There, he met one of his mentors, James Aggrey, the college’s first African faculty member and vice principal, who later convinced Nkrumah to study in the United States.

The young Ghanaian set off for this country in 1935. French describes the voyage as “an odyssey in three parts,” which included soliciting money from a relative, hiding among crew members on a ship, and making a stop in Liverpool, where he was briefly hosted by Paa Grant, the first president of the United Gold Coast Convention, or UGCC—a political party that would play a significant role in Nkrumah’s return to Ghana and early days as a political leader. Nkrumah was an ambitious but socially reserved figure: Though charming and beloved, he seemed fundamentally lonely. French ruminates on Nkrumah’s romantic life (or lack thereof, until his unexpected marriage to Fathia Halim Rizk in 1957) and wonders how this charismatic leader could be so awkward—occasionally bordering on juvenile—around women. These kinds of details, though clumsily deployed by French at times, effectively humanize Nkrumah, grounding a figure who is so often spoken of as more of a prophet than a man.

In the United States, where he would spend nearly a decade, Nkrumah majored in sociology at Lincoln University, enrolled in the theological seminary, and earned master’s degrees in education and philosophy from the University of Pennsylvania. While he studied, taught, and spoke in various public forums, Nkrumah’s “compass was fixed on the liberation of his continent, and most of his intellectual pursuits were bound up in his busy search for answers to the challenges of ending colonial rule and economic dependence on the West,” French writes. Nkrumah devoured everything about Pan-Africanism, which in its initial form (posited by intellectuals like James Beale Horton, Martin Delany, and J.E. Casely Hayford) explicitly responded to Western imperialism and focused on the development of a free state. Some scholars proposed a regional university in West Africa that could serve as a hub for a new imperial core, while others suggested Africans return to Indigenous forms of self-government, in which otherwise autonomous communities formed a united federation. Later versions, especially the kind promulgated by W.E.B. Du Bois, focused on intellectual unity, moral questions, and diplomatic relations between Africa and her diaspora. Both schools of thought emphasized an idea that Nkrumah found deeply compelling: the interdependence of Black people across the world. By the early 1940s, French writes, Nkrumah was fully invested in the notion “of a shared past in racial domination between Africans and African Americans” and “a closely paired future.”

In May 1945, at the tail end of World War II, he left the United States for London, where he met the Trinidadian journalist George Padmore by way of C.L.R. James. Both men were critical to Nkrumah’s intellectual development; they took him under their wing and helped him to fortify and clarify his positions. Through Padmore, especially, Nkrumah came to appreciate the urgency with which Africa’s colonies needed to seize “the levers of government.”

Armed with these experiences, Nkrumah returned to Ghana in 1947. This was a pivotal period in global politics, when colonized peoples were “increasingly alive to the injustice and humiliation” of the current system. Nkrumah dove headfirst into organizing. He joined the UGCC (the organization headed by Grant, who hosted him in Liverpool) and quickly took to its revitalization. He gave speeches around the country and launched local party offices, which helped galvanize once disparate colonial subjects under a single banner of unity. He became a sensational force and a thorn in the side of the British.

As Nkrumah breezes through the ranks of colonial government, French maintains a reverent yet clear-eyed perspective of the upstart’s journey. There’s an instructive focus on the details of organizing, with French highlighting how Nkrumah extended his political outreach through education and media. In 1948, he opened a small school called the Ghana National College and staffed it with volunteer teachers; later that year, he started the Accra Evening News, which built a large readership. Nkrumah also formed a nationwide association of young people, and before long, much to the dismay of the old guard UGCC, he and these new followers broke away to form their own party, called the Convention People’s Party. It’s with the CPP that Nkrumah rose to power and secured the nation’s independence.

French describes Ghana’s independence movement and the U.S. civil rights struggle as “linked and intertwined like a double helix,” in large part because of the “spirit of Pan-Africanism.” He explores how international Black activists inspired the civil rights movement and how African Americans influenced U.S. politicians to engage seriously with Nkrumah’s government in Ghana. Stateside publications like Jet and Ebony as well as local Black papers covered the former British colony’s struggle in detail and kept African Americans informed about progress in the region. This drummed up domestic support, which played a huge, but historically overlooked, role in “creating space for Nkrumah amid the stark and hostile East-West competition of the early Cold War” and even forced an unwilling Richard Nixon to attend Ghana’s independence ceremonies in 1957. African Americans would show a similar level of advocacy a few years later when Lumumba helped wrest Congo from Belgian rule, a saga French recounts in the book.

Yet Nkrumah’s Pan-Africanist dreams were not simply realized by severing from a colonial power. Local leaders and the ruling classes of these newly freed nations “were as disinclined to surrender their power and privilege to a larger and untested entity as they were to remain under colonial domination,” French writes. It’s a concern that the activist and political leader Andrée Blouin articulated in her 1983 autobiography, My Country, Africa, which was republished by Verso earlier this year. While helping Lumumba organize Congo’s independence process, Blouin worried about the new nation being undone by parties more interested in power than people. “There are politicians among us who serve neocolonialism for their own interests, and they sell out their black brothers and sisters to do so,” she wrote. “They are our worst enemies.”

Blouin’s concerns about the selfishness of the elite class periodically came to mind as I read French’s account of Nkrumah’s struggle to realize his ambitious projects in Ghana. For years, Nkrumah tried implementing a socialist scheme—which required cocoa farmers to invest a percentage of their earnings into government—to help fund his Volta River Project, a hydroelectric dam that he hoped would spur an industrial revolution and modernize the young nation. Instead, he was forced to seek help from an “international economy dominated by big Western companies whose structure offered poor nations almost no chance at real prosperity.” These obstacles only fueled Nkrumah’s obsession with the Volta project and distracted the leader from addressing domestic issues. Inflation was out of control and the price of cacao—a major export—remained low, further upsetting an already disgruntled populace.

For the most part, French offers a charitable analysis of Nkrumah’s eventual downfall. He doesn’t defend the president’s increasingly authoritarian decision-making, but he does provide a generous amount of context, including examining how a 1962 assassination attempt made Nkrumah more reclusive and paranoid. These conditions set the stage for his eventual overthrow in 1966 by the Ghanaian military. That year, he fled to Guinea, where he spent the rest of his life before he died of cancer in Bucharest in 1972.

What French does well in The Second Emancipation is remind readers that whatever the struggles faced by individual leaders, credit for African nations’ present-day precarity can only go to plundering empires. That the world was (and is) organized to benefit Western powers made Nkrumah’s persistence in realizing even a sliver of his goals all the more impressive. In May 1963, a few years before the coup, Nkrumah held the first summit of the Organization of African Unity in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. It was one of the first times that African countries gathered to discuss their own fate. Sadly, the ideas presented to the convention of 32 African leaders never gained traction. They gently rejected proposals for a federal structure, a common currency, the abolition of current borders, or any of Nkrumah’s other radical ideas. What could have been achieved had his visions been given a chance?

Today, as the global majority finds itself once again navigating the turbulence of fractious superpowers, this question gains new urgency. On the one side of the world order stands the United States, still collaborating with Israel to annihilate Palestinians. On the other side is Russia, whose war on Ukraine continues unabated. Climate change is another arena in which the world’s non-superpowers have found themselves effectively abandoned: The global north is responsible for roughly 92 percent of excess carbon emissions while countries in the global south suffer most from the damage.

But when South Africa brings a genocide case against Israel before the International Court of Justice, or when Zambia, Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Burundi unite to protect vital natural resources around Lake Tanganyika, it’s evidence of a shifting global consciousness, and an occasion to think about the role Pan-Africanism can play right now.

This past summer, I went to Nairobi for the launch of the first print edition of Africa Is a Country magazine. The issue surveyed how the past 15 years have been defined by mass mobilizations, such as the Arab uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa (and, I would add, the early Black Lives Matter protests in the United States). Each contributor tried to understand Africa’s place in these movements and how, as William Shoki wrote in an editor’s note, we transition from “eruption to organization, from euphoria to endurance.”

The launch event was only days removed from protests against Kenya’s President William Ruto, and the energy from those demonstrations animated the room and the conversations between a range of people—from Kenyans and South Africans to Comorians and Nigerians. As we exchanged ideas, asked questions, and shared histories, it occurred to me that this convening drew on the spirit of Pan-Africanism, and that the future of the continent, much like its past, depended on that movement’s survival.