Twelve years ago, the Supreme Court held in a 5–4 decision in Maryland v. King that police departments could perform cheek swabs on people they take into custody and use the DNA sample for criminal investigations. The case is memorable not only for its ruling but for the vivid dissent by Justice Antonin Scalia and three of the court’s liberals at the time.

Scalia argued that suspicionless searches for criminal evidence, like the cheek swabs in question, cut against the core of the Fourth Amendment’s principles. “Perhaps the construction of such a genetic panopticon is wise,” he wrote, joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan. “But I doubt that the proud men who wrote the charter of our liberties would have been so eager to open their mouths for royal inspection.”

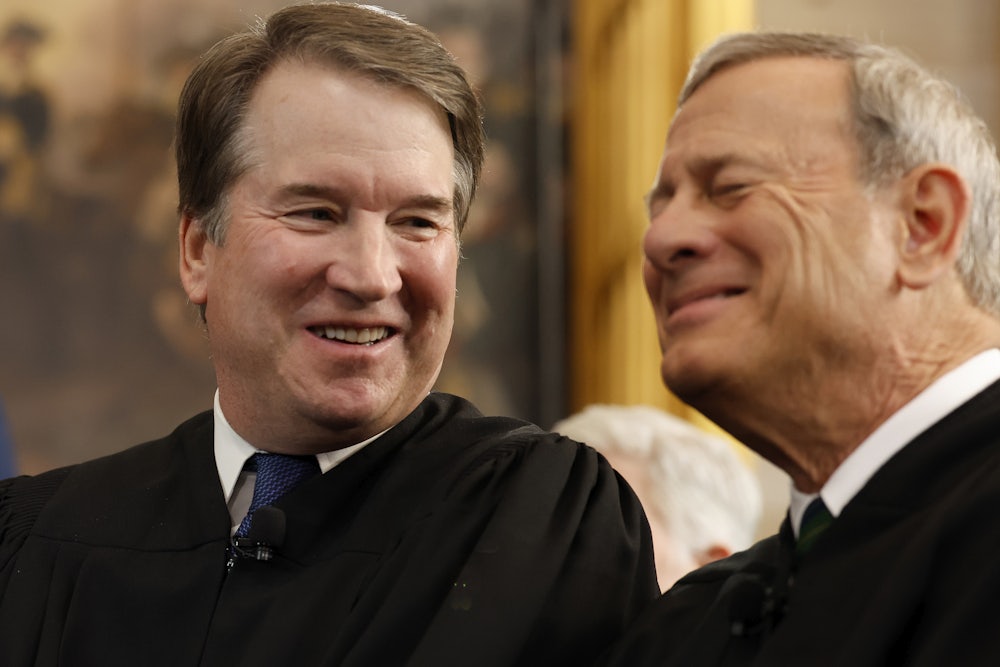

In a strange turn of events, however, the actual decision in King may turn out to be less legally significant than a then–largely unnoticed administrative ruling that Chief Justice John Roberts handed down when the case reached the court. His relatively minor decision at the time laid the groundwork for the court’s whipsaw tilt in favor of the Trump administration’s policies—and how it understands the concept of “irreparable harm” in its shadow docket cases.

Maryland enacted its DNA Collection Act in 1994 at the dawn of the age of DNA forensic testing. While DNA testing methods had been used by law enforcement before the act’s passage, they did not burst into the public consciousness until 1995, when they played a central role in the O.J. Simpson trial. The Maryland law allowed police to take DNA samples from a suspect when they apprehended him for violent-crime charges and compare them to a state database.

Alonzo King, the titular defendant in the case, was arrested in 2009 on assault charges. Police obtained a DNA sample from him while processing him in the local jail. When they compared it to the state database, they found a match with an unidentified sample taken from a 2003 rape case. Thanks to the DNA match, they charged him with the previously unsolved crime and obtained a conviction from a local jury.

On appeal, King argued that the 1994 law violated the Fourth Amendment because it represented a suspicionless search for criminal evidence. Maryland argued (and the five-justice majority on the Supreme Court agreed) that it was permissible because it was akin to fingerprinting, which had been a standard police booking practice over the prior century. The Maryland Court of Appeals sided with King in 2012, prompting the state to ask the Supreme Court to review the case.

After filing a petition for review, Maryland also asked the high court to stay the Maryland Court of Appeals’ ruling pending the outcome of the appeal. This request was processed not through the court’s regular merits docket but through its emergency docket. (Three years later, legal scholar William Baude would coin the term “shadow docket” to describe its workings.)

For the shadow docket, each of the nine justices is assigned to cover at least one of the federal circuit courts of appeals. There are 13 of them—the First through Eleventh Circuits for the states, the D.C. Circuit for the District of Columbia, and the confusingly named Federal Circuit for the special-jurisdiction federal courts. Roberts, by tradition, always takes the D.C. Circuit, the Federal Circuit, and the Fourth Circuit, which covers the states surrounding the nation’s capital.

When a motion to stay a lower court’s judgment reaches the Supreme Court, it first goes to the “circuit justice” assigned to review. This is a reference of sorts to the now-defunct practice of justices “riding circuit” on literal horseback to hear appeals in the early republic. In their capacity as a circuit justice, the court’s members serve as a filter of sorts: They resolve uncontroversial motions on their own, refer significant ones to the rest of the court, and grant administrative stays on emergency matters until the other eight justices can meet.

In this capacity, Roberts was asked to decide whether Maryland could continue to collect DNA samples despite the lower court’s ruling while the Supreme Court considered the case. This should be a tall order, out of respect for the lower courts, but not an insurmountable one. Under the high court’s precedents, Roberts explained, a litigant has to show that there is a “reasonable probability” that the Supreme Court will take up the case, that there is a “fair prospect” that the Supreme Court will reverse the lower court’s ruling, and that it is likely that “irreparable harm” will result if the stay is not granted.

Roberts noted that Maryland easily met the first prong of the test: The Maryland Court of Appeals’ ruling had conflicted with two federal appeals courts and a neighboring state supreme court, so it was reasonable to assume that the Supreme Court would decide an important Fourth Amendment question. Since multiple appellate courts had disagreed with Maryland’s answer to that question, Roberts explained, it was possible that the Supreme Court would as well. So far, so good.

Then Roberts reached the “irreparable harm” part of the test. Much of his reasoning was centered on the virtues of the law and “an ongoing and concrete harm to Maryland’s law enforcement and public safety interests” if the law were blocked, even temporarily. He also included this sentence as legal authority: “Any time a State is enjoined by a court from effectuating statutes enacted by representatives of its people, it suffers a form of irreparable injury.” (For the sake of clarity and brevity, we will hereafter refer to this as “the King line.”)

The King line is a partial quote—and the partialness of it is important—from an opinion that William Rehnquist, Roberts’s predecessor as chief justice, wrote in the 1977 case New Motor Vehicle Board v. Orrin W. Fox Company. At issue in that case was a California state law that required franchised car dealerships—that is, dealerships that purchased the right to sell cars from a specific manufacturer—to notify a state agency and the dealers’ nearby competitors whenever they established or moved their place of business. The competitors could then intervene with the board to stop the dealership from opening or moving locations.

General Motors and two local dealers sued the state to overturn the law, arguing that the right to establish and move their businesses was protected by the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause. They prevailed in the lower courts, so the board sought review from the Supreme Court. Along the way, the board asked then-Justice Rehnquist, acting in his capacity as circuit justice, to lift the stay while the litigation continued.

Rehnquist agreed with the agency. He disagreed with the lower courts’ decision on multiple grounds, many of which were related to the merits of the case itself. Here is the paragraph from which Roberts got the quote. I include it at length here not because the overall legal argument is relevant but because it illustrates the nature of the comment. (Emphasis mine.)

Respondents argue that the State is not injured by the injunction, because the proposed relocations are almost invariably approved, and therefore even if the District Court was wrong on the merits, a stay should not be granted. This argument casts too narrowly the purpose of the statute and the injury to the State, however. The interest of the State does not necessarily find expression through disapproval of relocation plans, but rather through the act of examining the proposed relocations to make sure that existing dealers are not being impermissibly harmed by the manufacturer, and that the move is otherwise in the public interest. This interest is infringed by the very fact that the State is prevented from engaging in investigation and examination. And the occasion for this review may arise often during the time this injunction is in effect. In an affidavit presented to the District Court, Sam W. Jennings, Executive Secretary of the New Motor Vehicle Board, indicated that, in the first 44 days following the issuance of the District Court’s injunction, the Board received 99 notices of intent to relocate or establish new dealerships in California. Under the terms of the injunction, all those applicants will be allowed to locate dealerships without undergoing any scrutiny by the State. And assuming the State eventually prevails on the merits and the injunction is lifted, it is not at all clear that the New Motor Vehicle Board will have the authority to examine the propriety of all those relocations or to force those relocated dealerships to stop doing business. It also seems to me that any time a State is enjoined by a court from effectuating statutes enacted by representatives of its people, it suffers a form of irreparable injury.

Rehnquist was not delivering some long-winded summation of precedent here, nor was he elaborating specifically upon the separation of powers between the judiciary and legislative branch. His assertion is almost an aside, an afterthought, or an observation at the end of a much more considered study of how an injunction’s real-world consequences would play out.

Taken as a whole, he was referring to a principle in American constitutional law known as the “presumption of constitutionality.” Under this doctrine, courts generally assume that a duly enacted state or federal statute is constitutional unless proven otherwise. But there are limits to how far that presumption can go. Economic regulations, for example, receive only “rational basis” review. Courts generally uphold their constitutionality so long as the government has a rational basis for enacting them.

Laws that affect constitutional rights, on the other hand, do not generally receive this presumption. They are instead viewed through the lenses of judicial scrutiny that the high court has carved out over the years. Whether they receive intermediate scrutiny or strict scrutiny, it is the government’s burden to overcome. As Rehnquist explained in his 1977 opinion, that was not a factor in that particular case because he did not believe the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause protected the purported right that the dealerships asserted.

In King, Roberts transmuted Rehnquist’s musing into a more authoritative dictum. “It also seems to me” was dropped in favor of a more absolute bracketing: “Any time a State is enjoined by a court from effectuating statutes enacted by representatives of its people, it suffers a form of irreparable injury.” He then applied it to the case at hand, albeit not as the entire basis of his opinion. (I refer to it as the King line because it substantially modified what Rehnquist said to sound more definitive.)

Steve Vladeck, a Georgetown University law professor, noted in a 2019 law review article on the subject that Rehnquist had a more expansive view of the presumption of constitutionality when considering these types of motions than his colleagues. Other justices would use the presumption of constitutionality as one factor among many for them to weigh when reviewing motions for stays. Rehnquist, on the other hand, treated it as a freestanding rationale to allow challenged laws and policies to take effect “without almost any regard to the other equities involved in the particular case,” Vladeck explained. Roberts, he noted, has followed suit.

Since Trump’s return to office, the court has expanded the stated principle beyond even what Rehnquist had articulated. In Trump v. CASA earlier this year, for example, Roberts and his conservative colleagues cited it to restrain lower courts’ ability to issue nationwide injunctions against the Trump administration—and, in that specific case, against its efforts to end birthright citizenship. That prompted some pushback from Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who noted that this principle could not overrule the Fourteenth Amendment’s citizenship clause.

She argued instead that the “democratic consideration” went against the Trump administration in this case. “Through the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, Congress and the States constitutionalized birthright citizenship,” Sotomayor explained. “Congress also codified birthright citizenship in Section 1401(a). It is thus the [executive order], not the district courts’ injunctions, that prevents the ‘effectuat[ion]’ of a constitutional amendment and repeals a ‘statut[e] enacted by representatives of [the American] people.’”

By including the line in CASA, however, the conservative majority gave it the Supreme Court’s collective imprimatur. Earlier this week, in Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo, Justice Brett Kavanaugh expanded the King line even further to cover discretionary actions by the executive branch. His opinion is not the opinion of the court—the other five justices did not write one, as is common in shadow docket cases—but it is indicative of the direction in which the court is going. This is his analysis on the “irreparable harm” question, showing the flow from older cases to more recent ones:

The Government has also demonstrated that it would likely suffer irreparable harm if the District Court’s injunction is not stayed. As the Court has indicated, “‘“[a]ny time” ’” that the Government is “‘“enjoined by a court from effectuating statutes enacted by representatives of its people, it suffers a form of irreparable injury.”’” Trump v. CASA, Inc., 606 U. S. ___, ___ (2025) (slip op., at 25) (quoting Maryland v. King, 567 U. S. 1301, 1303 (2012) (ROBERTS, C. J., in chambers)).

“So it is in this case, particularly given the millions of individuals illegally in the United States, the myriad ‘significant economic and social problems’ caused by illegal immigration, and the Government’s efforts to prioritize stricter enforcement of the immigration laws enacted by Congress,” he continued, tipping his hand on what he thought of the merits. Except the plaintiffs in this case were not challenging any “statues enacted by representatives of [the] people”—they were challenging alleged racial profiling by armed and masked executive branch officials.

The overall result here is a sudden inversion of how the court balances the equities in ongoing litigation. Instead of weighing the irreparable harms to both parties, as well as the other traditional relevant factors for these shadow docket cases, the Roberts court has given the federal government a potent card to play against litigants who want to stop ongoing harms.

And while the King line is a purportedly democratic principle that exalts the legislative process, its current breadth suggests otherwise. It is the Constitution that allows Congress to pass laws and the executive branch to enforce them. The Roberts court’s professed deference to statutes and elected representatives is now being used by the Trump administration to violate Americans’ rights while months or years of litigation take place, so long as they claim they are enforcing a law along the way. It is serendipitous that Roberts’s formulation came in a case titled Maryland v. King, because the King line effectively allows the president to rule as one.