As the United States veers toward renouncing its free speech commitments, it’s worth once again asking why we have a First Amendment free speech tradition in the first place. The answer, it turns out, has everything to do with managing the problem of political violence in the modern world. And it’s an answer that the federal government today ignores at our peril.

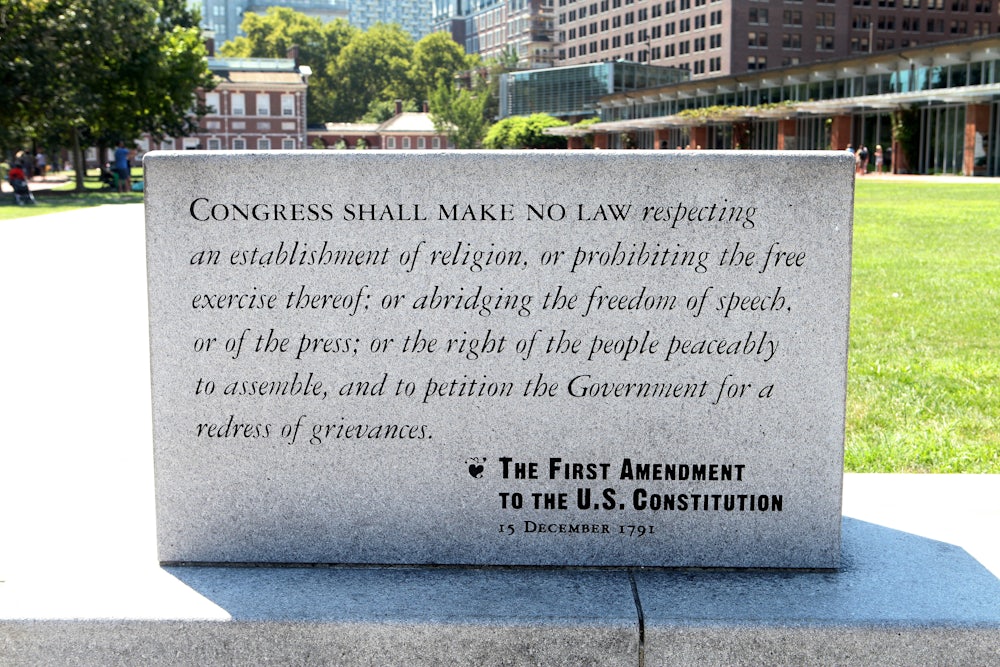

At first glance, the question seems to answer itself. According to the usual story, in 1791, the states ratified the First Amendment to the Constitution as part of a package of rights-protecting additions to the new Constitution ratified three years prior. The Framers and ratifiers of our basic national compact treated these amendments, which together soon came to be called the Bill of Rights, as a condition of ratification.

But if we push deeper, this folktale quickly falls apart. It was not until 1927 that the Supreme Court sided with a speaker under the First Amendment. The speech clause did not apply to the state governments at all until a century ago. And until the 1920s and 1930s, the basic rule of free speech (in federal courts and state courts alike) codified the old English common-law doctrine against prepublication censorship. Once uttered or published, words deemed to have bad effect could be grounds for punishment—and they often were.

What changed? Many lawyers look to the influence of heroic dissenting justices on the Supreme Court in the speech cases that came to the court at the end of the First World War, when Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and Louis Brandeis opposed the Supreme Court’s routine application of the old common-law tradition in cases affirming the conviction of antiwar protesters and left-wing radicals.

Yet the Holmes and Brandeis story attributes far too much power to the court and its justices—and to two dissenters, no less. Holmes and Brandeis did not invent free speech; instead, they channeled an innovative new idea about the relationship between the state and speech—one that had been invented in the previous decade by a group of sophisticated statesmen and thinkers managing the problem of political violence in America.

For two decades and more, anarchists and members of the Industrial Workers of the World, or IWW, had engaged in a wild set of bombings and assassinations, from Haymarket Square in Chicago in 1886 to the assassination of President William McKinley in Buffalo in 1901, to the destruction of the Los Angeles Times building in 1910.* The mayhem included a nationwide assassination campaign of mail bombs in 1919, as well as the 1920 wagon-bombing of Manhattan’s Financial District, whose destructive force is still visible today in a pock-marked exterior on Wall Street.

Against this backdrop, free speech appealed to statesmen attuned to the dynamics of mass democratic politics. When the Wobblies (as the IWW men were known) launched free speech fights in towns across the West, a police commissioner in Denver named George Creel decided to allow the radicals to speak their piece. In New York City in 1914, Police Commissioner Arthur Woods declined to interfere in an anarchist memorial at Union Square on behalf of a would-be Rockefeller assassin. Protests that had caused crisis in Fresno, Missoula, San Diego, and Spokane soon fizzled without the added electricity of mass arrests.

During the First World War, a contingent of key Wilson administration insiders such as George Creel—the former Denver police commissioner, who now took up the role as Wilson’s chief propagandist—and journalist Walter Lippmann blocked the most aggressive wartime censorship plans favored by rivals in the administration like the young Douglas MacArthur and heavy-handed Texas politicos such as Attorney General Thomas Gregory and Postmaster General Albert Burleson.

Men like Lippmann believed that in the modern world, outlawing speech would create what he called the taboo effect: Forbidding speech added to its allure. For Lippmann and his innovative statesmen allies, there were several political virtues for free speech so far as the state was concerned. Speech armed the state and its officials with information about the views of the public. It outed dissenters, including potentially dangerous ones. It facilitated sensible surveillance. It defeated martyrdom tactics, as practiced by the Wobblies in the West and the anarchists in the East. And it offered an outlet for passions that otherwise, if bottled up, might explode in violence.

Justice Brandeis said as much in 1927 when he observed that repression breeds hate and that free speech is “the path of safety.” The Supreme Court majority came around four years later when Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes wrote that free political discussion existed so that political change “may be obtained by lawful means” as opposed to unlawful ones. Four decades later, First Amendment scholar Thomas Emerson formalized the point into what has come to be known as the “safety valve” theory of free speech.

All this was, until recently, so well settled in our political ecosystem that we’ve nearly forgotten it. Today, the short-term threats to the consensus are all too visible. But there are long-term threats, as well. Will twenty-first-century surveillance technologies from places like Palantir technologies undermine the argument that free speech provides the government with vital information? Will the ability to marshal brute power in a federal police force embolden officials to think that they can successfully suppress dissent? Will the apparent success of such efforts in nondemocratic state capitalist regimes like China persuade this White House or its successors that it can do away with the insights of Lippmann’s generation? Perhaps. But not in a nation recognizable to those who treasure the traditions of nonviolent protest that free speech has helped bring us.

* This article originally misidentified the date of the Los Angeles Times bombing.