It was 1859. The analogies to the current state of American politics are not precise and even paradoxical. To begin with, John Brown, though crazy and bloodthirsty, was on the right side of history. He preferred wielding guns to scoring debating points. He had utter contempt for politicians, electoral campaigns, and the Constitution. In fact, he wrote his own to replace it. The last thing on his mind was making money off his cause. After his execution, Brown was venerated as a Christ-like martyr. He bore not the slightest resemblance to Charlie Kirk or his murderer, except in the strain of zealotry.

But the political manipulation of violence after John Brown’s raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia), on October 16, 1859, the launch of an inquisition against the fledging antislavery Republican Party, the defensive reactions of its senior figures, and the way Abraham Lincoln summed up the whole problem to emerge as the new party’s national leader may provide strikingly instructive lessons.

Consider these parallels: After a shocking act of domestic terrorism, the powers that be organized a seemingly overwhelming wave of political retribution. At the moment of the attack, their control had become shaky; their president (James Buchanan) was unpopular, and the opposition was gaining ground. At once, they seized upon the violent incident as the means to maintain power and cast blame on their opponents. Vengeance ruled the day. Paranoia was sharpened to a fine point.

The entire opposition political party was charged with responsibility for murder (17 were killed in Brown’s raid, including one U.S. Marine). The federal government conducted a dragnet to arrest those behind the conspiracy. Books were banned, schools shut down. The Supreme Court had already ruled that the opposition party’s central platform plank was unconstitutional. On the House floor, members nearly came to blows.

The opposition party reeled in retreat. On the defensive and lacking a strategy, its most prominent leaders simply professed innocence, condemned terrorism, and proclaimed moderation. Rather than confront the politics of paranoia, they hoped the excitement would dissolve through emollient words that would somehow restore a modicum of normalcy to American politics. The radicals, meanwhile, celebrated the terrorist as a hero, giving easy material with which to smear the party politicians. It turned out that some of the most eminent radicals were, in fact, not only encouraging but providing the funds for arming the violent conspiracy.

As hysteria and repression rose, no one had emerged to articulate arguments that broke through the atmosphere and that stated the opposition’s position in moral terms. Almost everyone in the opposition seemed flustered, apologetic, or intimidated. Leadership was a vacuum.

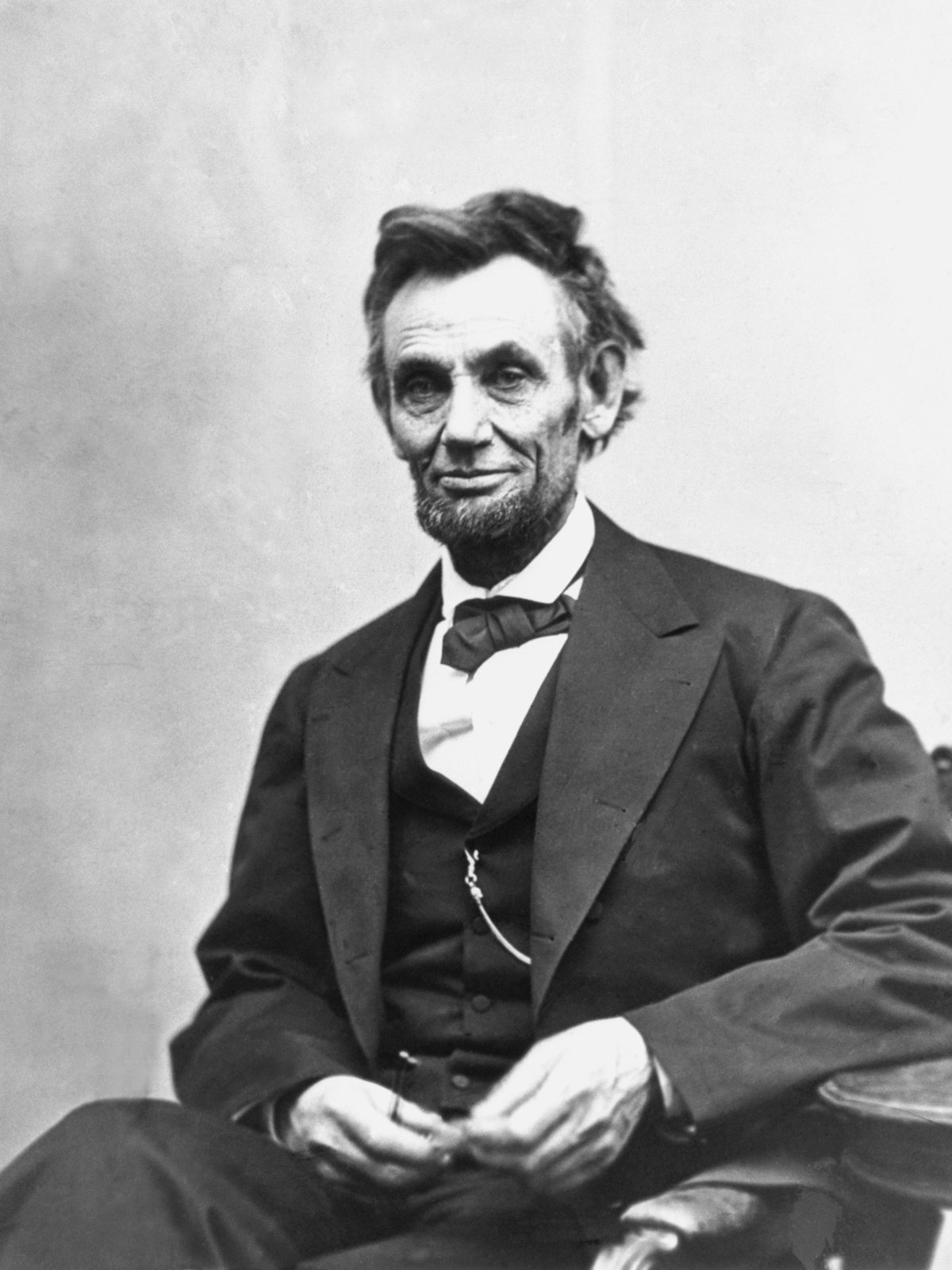

On the eve of these events, Abraham Lincoln—then out of office, having lost a Senate race the year before—received a telegram on October 12 inviting him to speak in New York City in four months before a group of Republicans on “any subject.” The Republicans were holding an ongoing forum at the Cooper Institute to hear firsthand a series of potential presidential candidates for the 1860 nomination. Lincoln’s debates with Stephen A. Douglas in their Illinois Senate contest of 1858 had been published at length in the New York newspapers at the time, but no more than a handful of New Yorkers had ever seen Lincoln. He was a curiosity from the prairie, and the darkest of dark horses, especially given that he had lost the year before. For months, Lincoln worked alone on his speech as part constitutional case study, part political strategy, and part moral statement.

Four days after Lincoln received the invitation, on October 16, 1859, Brown led his raid, intended to spark a slave insurrection. In “Bloody Kansas,” where proslavery and free-state militias had battled since 1854 for control of the territory, Brown had roamed with his own murderous gang, claiming to sanctify a righteous cause with violence. Frederick Douglass refused Brown’s offer to join his band of misfits and warned him that his raid would be suicidal. But Brown’s fanaticism had impressed notable abolitionists from Boston and New York as a higher morality; ignoring his homicidal impulses and calling themselves the Secret Six, they financed his fiasco.

The Six were an extraordinary group. Two were wealthy longtime donors of the abolitionist cause—Gerrit Smith, perhaps the largest landowner in New York, and George Luther Stearns, a manufacturer from an old Massachusetts family. Two were Unitarian ministers—Theodore Parker led the Boston church attended by the great transcendentalists, and Thomas Wentworth Higginson would become the colonel of the first Black Union army regiment and the mentor of Emily Dickinson. Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe was a renowned reformer, founder of the Perkins School for the Blind, and married to Julia Ward Howe, who would write the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” And there was the journalist Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, later the founder of the American Social Science Association.

The first person that Brown’s raiders killed was a free Black man who worked for the railroad; the second was the town’s mayor. Brown was quickly captured by soldiers led by Colonel Robert E. Lee, tried, found guilty, and executed. John Wilkes Booth was in the front row before the gallows and admired Brown’s fanaticism. Brown left behind an eloquent prophesy that “this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood,” and a trunk full of incriminating documents about his co-conspirators, several of whom fled the country. Douglass, fearful for his life, sailed for safety to England.

The South Carolina legislature sent a commissioner to Southern states to organize a secession conference. Northern traveling salesmen in the South were tarred and feathered, a liberal college in Kentucky closed, and northern newspapers confiscated and burned.

The bestselling book in the country, circulated by the Republican Party, was banned throughout the South. The Impending Crisis in the South, written by Hinton Helper, a North Carolina abolitionist, was filled with statistics showing how the “slave-owning oligarchy” was also the master of the “non-slaveholding whites, whose freedom is merely nominal, and whose unparalleled illiteracy and degradation is purposely and fiendishly perpetuated.”

On the floor of the House, Congressman Owen Lovejoy of Illinois—whose brother Elijah, an abolitionist editor, had been murdered in 1837 by a proslavery mob in Alton, Illinois, an act denounced by the young Lincoln—endorsed Helper’s book. A fire-eating congressman from Virginia, Roger Pryor, threatened to have Lovejoy hanged like Brown. Another representative, John F. Potter, of Wisconsin, interceded. Pryor challenged him to a duel. Potter suggested bowie knives, which prompted Pryor to back out.

The Senate created a select committee to investigate the conspiracy behind the Brown raid. Its chairman, Senator John M. Mason, of Virginia, had been the sponsor of the Fugitive Slave Act, and its chief prosecutor was Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi. Davis announced that his target was Senator William Seward of New York, presumed to be the Republican Party presidential candidate in 1860. Davis, sounding not unlike Donald Trump when he talks today about his political antagonists, charged that Seward “knew of the Harpers Ferry affair,” and “deserves, I think the gallows, for his participation in it.” Seward and other leading Republicans were subpoenaed.

Douglas, who had vanquished Lincoln in that Senate race and now stood as the presumptive Democratic nominee for 1860, took to the Senate floor to declare that Brown’s raid was “the logical, natural consequence of the teachings and doctrines of the Republican Party.” He accused both Seward and Lincoln of incitement and proposed a sedition act.

Seward responded with a speech in the Senate that he thought would guarantee him the Republican nomination. He had been the first antislavery man elected to the Senate, his upstate New York home a station in the Underground Railroad. But now he delivered a meandering oration to reassure the South that Northern states believed in “white man’s pride,” that Brown had committed “treason,” and that the “agitation” would soon subside. Seward was groping for a new conventional wisdom to serve as solid ground on top of an earthquake, but he misjudged the mood within his own party very badly indeed, appearing to be conceding to the Slave Power.

Seward’s speech accelerated the whirlwind. “His calls for civility blaming both sides in a false equivalence only stirred his enemies to assail him further,” I wrote in my book covering the entire crisis, All the Powers of Earth: The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln 1856-1860. Seward was besieged on all sides. “So passionless,” editorialized the New York Tribune.

Such was the context in which Lincoln mounted the podium at the Cooper Institute, today’s Cooper Union, on February 27, 1860. He was described by members of the audience as “ungainly,” “awkward,” his hair tousled, his voice high-pitched, “thin,” and “squeaky.” After a few introductory words, “his face lighted up as with an inward fire; the whole man was transfigured,” wrote the correspondent for the Tribune.

Step by step, Lincoln laid out a strategic primer. His first imperative was to ground the antislavery politics of the new Republican Party firmly in the Constitution. The fundamental position that unified the disparate elements of the party was the prohibition of slavery in the territories. Slavery was the cause of “Bleeding Kansas.” The Supreme Court had attempted to outlaw the Republican platform in the Dred Scott decision, in which Chief Justice Roger B. Taney stated that the founders believed that Black people “had no rights the white man was bound to respect,” that the Declaration of Independence’s credo “All men are created equal” did not apply to them, that they were “an article of property” and thus could never be citizens, and could be taken as slaves into the territories.

Lincoln, the forensic lawyer, presented the evidence to refute Taney’s bogus originalism, showing through his historical research that the majority of the framers of the Constitution had in fact supported “congressional prohibition of slavery in the federal territories.” Thus, the Republican Party and its antislavery position was constitutionally rooted.

He swiveled to address the Southerners, saying, “When you speak of us Republicans, you do so only to denounce us as reptiles, or, at the best, as no better than outlaws. You will grant a hearing to pirates or murderers, but nothing like it to ‘Black Republicans.’” One after another he brought up their charges, tore them apart and concluded: “We deny it.”

Then he came to Brown’s raid, which “defines Black Republicanism to simply be insurrection, blood, and thunder among the slaves.” Lincoln described the true motive of this rhetoric as an attempt to influence elections: “When it occurred, some important state elections were near at hand, and you were in evident glee with the belief that, by charging the blame upon us, you could get an advantage of us in those elections.”

Lincoln drew back to put Brown into perspective against a broader background of political assassination. “That affair, in its philosophy, corresponds with the many attempts, related in history, at the assassination of kings and emperors. An enthusiast broods over the oppression of a people till he fancies himself commissioned by Heaven to liberate them. He ventures the attempt, which ends in little else than his own execution. Orsini’s attempt on Louis Napoleon and John Brown’s attempt at Harpers Ferry were, in their philosophy, precisely the same.” Felice Orsini was an Italian revolutionary who threw homemade bombs at Napoleon III’s carriage, killing eight people but not the emperor. Orsini was tried and guillotined.

Again, Lincoln returned to the underlying political motives of the accusers. “And how much would it avail you if you could, by the use of John Brown, Helper’s book, and the like, break up the Republican organization? Human action can be modified to some extent, but human nature cannot be changed. There is a judgment and a feeling against slavery in this nation.… You cannot destroy that judgment and feeling—that sentiment—by breaking up the political organization which rallies around it.”

Lincoln carried his logic to its conclusion, that the impulse to repress free speech and democracy would lead to more terrorist acts. He posed the question: “How much would you gain by forcing the sentiment which created it out of the peaceful channel of the ballot-box, into some other channel? What would that other channel probably be? Would the number of John Browns be lessened or enlarged by the operation?”

Lincoln brought his case back to the Constitution. “When you make these declarations, you have a specific and well-understood allusion to an assumed constitutional right of yours to take slaves into the federal territories, and to hold them there as property. But no such right is specifically written in the Constitution. That instrument is literally silent about any such right. We, on the contrary, deny that such a right has any existence in the Constitution, even by implication. Your purpose, then, plainly stated, is that you will destroy the government unless you be allowed to construe and enforce the Constitution as you please, on all points in dispute between you and us. You will rule or ruin in all events.”

Lincoln turned to speak to his fellow Republicans. First, he said, “Even though much provoked, let us do nothing through passion and ill temper.” Then, he explained the depth of the political problem that they faced. They would be continually put on the defensive. Even if the territories were “unconditionally surrendered” to the South, that would not satisfy them. Even if there were no more “invasions and insurrections … yet this total abstaining does not exempt us from the charge and the denunciation.”

His lessons were clear—to frame the central political issues as a defense of democracy and the Constitution, to repudiate smears by exposing the political motives behind them, to focus on winning elections by standing firmly on the fundamental questions rather than being provoked into sideshows, to understand that nothing but abject prostration before their enemies would satisfy their will to power, and to assert that the politics of fear must be met with confidence.

At last, Lincoln delivered his conclusion, disdaining deference and apology, freed from ambivalence and ambiguity, rising above vilification and bullying, to defend the Constitution, vindicate his party, and emerge as its standard-bearer. “Neither let us be slandered from our duty by false accusations against us, nor frightened from it by menaces of destruction to the government nor of dungeons to ourselves. Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.”

Lincoln’s speech at the Cooper Institute was the only speech he delivered in the four months before the Republicans nominated him for president. Perhaps some Democrat out there ruminating over 2028 will take the time to study how Lincoln navigated the politics of a house divided and take heed.