The Supreme Court appears poised to strike down President Donald Trump’s asserted power to levy billions of dollars in tariffs on American importers, delivering a crushing blow to his economic agenda and depriving him of his favored cudgel for foreign policy disputes.

The key questions going into Wednesday’s oral arguments were clear: Would the court’s conservative majority continue to show extraordinary deference toward the Trump administration’s sweeping claims of executive power? Or would it apply its existing precedents on the separation of powers to curb the executive branch’s usurpation of Congress’s authority to raise taxes and tariffs?

The justices appear to be headed toward the second path. All three of the court’s liberal justices were hostile to the administration’s argument that Trump’s tariffs were legal under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, or IEEPA. Multiple conservative justices also expressed deep skepticism. Among them was Justice Neil Gorsuch, who raised concerns about the permanent balance between legislative and executive power if the court upheld the tariffs.

“Congress, as a practical matter, can’t get this power back once it’s handed over,” he remarked, noting that it would take a supermajority of Congress to repeal IEEPA and overcome a likely presidential veto. He described the law’s breadth as a “one-way ratchet in the gradual accretion of power in the executive branch and away from the people’s representatives,” and he did not mean it as a compliment.

IEEPA, enacted in 1977, gives the president broad discretion to apply economic sanctions against foreign nations and groups during a declared national emergency. Past presidents have used it to freeze foreign assets in the United States, restrict trade with hostile countries, and prohibit certain forms of trade with foreign markets.

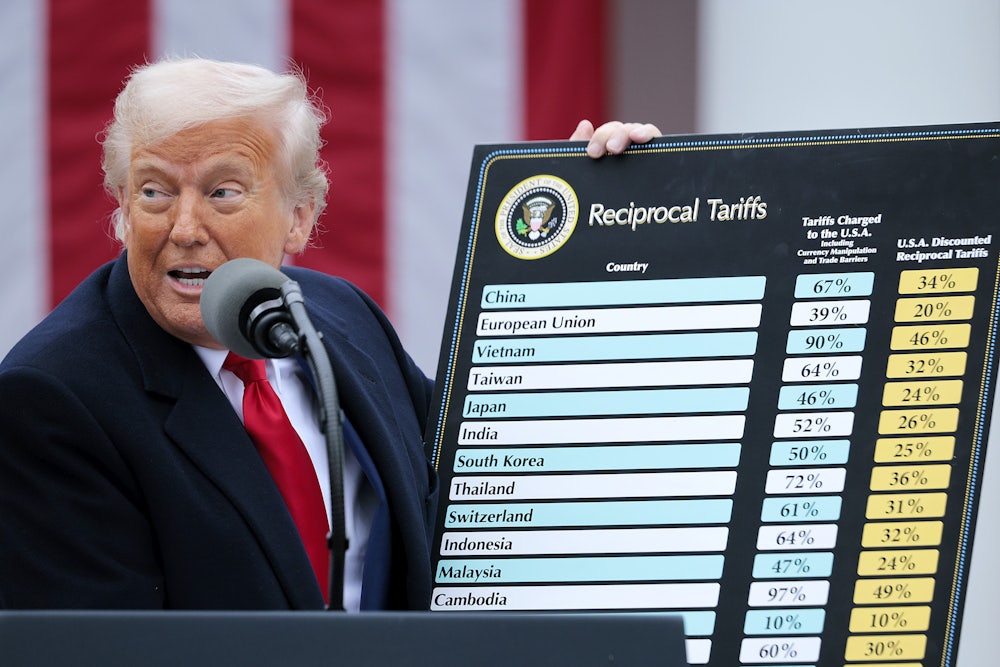

Starting this spring, Trump invoked IEEPA to apply tariffs to imported goods from countries like China, Mexico, and Canada as part of his trade disputes with those countries. In April, those efforts culminated in his “Liberation Day” order that applied 10 percent tariffs on all imported goods, along with much higher rates for dozens of countries.

The litigants in this case, which include a coalition of small businesses and state governments, argued that IEEPA gives the president no such powers. They claimed that the administration’s cited language—IEEPA’s grant of authority to “regulate importations” from foreign countries—did not extend so far as to include tariffs. Since the ability to raise tariffs is a core legislative power, they claimed, Congress could not have intended to transfer it to the president so freely through such vague language.

This argument was expected to find a receptive audience among at least some of the court’s conservative members. Over the past decade, the court has refined what it calls the “major questions doctrine” to block presidential policies of “vast economic and political significance” if it determines that Congress did not “speak clearly” in the law that the president cites as authority.

Using IEEPA to impose hundreds of billions of dollars in tariffs on virtually all U.S. imports would appear to fit that framework. Neal Katyal, who represented the businesses, argued that the revenue-raising implications only compounded their illegality. “Tariffs are taxes,” he told the justices in his opening remarks. “Our Founders gave that taxing power to Congress alone.”

The Trump administration has claimed in public messaging that tariffs aren’t taxes and often suggested that they are paid by foreign countries instead of American businesses and individuals. This strategy did not work in the Supreme Court, where the justices know better and where lawyers are generally obligated to be honest with them.

To address these questions on behalf of the government, Solicitor General D. John Sauer claimed that they were “regulatory tariffs,” not “revenue-raising tariffs.” He even went so far as to argue that “the fact that they raise revenue is only incidental” and that they would be “most effective if no one ever paid them.” (“Regulatory,” in this context, appears to mean something akin to “regulating the flow of goods across borders,” even though that doesn’t really make sense, either, in Sauer’s use of the term.)

A major problem for Sauer is that this is not how the Trump administration has described the tariffs anywhere else. Trump has often bragged about the large sums of revenue that he has been able to raise. Earlier this year, top officials like Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick were even floating the idea that the administration could abolish the IRS—and, presumably, the variety of taxes that it normally collects—and replace it with an External Revenue Service that oversees the tariffs.

A particularly awkward moment came when Chief Justice John Roberts squarely asked a question that the Trump administration often evades. “Who pays the tariffs?” he asked Sauer. “If a tariff is imposed on automobiles, who pays them?” Sauer’s dissembling and rambling answer about contracts between importers and exporters did not really answer the question. But in a much more fundamental way, it did.

Roberts spelled it out more clearly in a later exchange. “Yes, tariffs [are used] in dealings with foreign nations,” he remarked, “but the vehicle is imposition of taxes on Americans, and that has always been the core power of Congress.” The chief justice noted this as part of a discussion about how courts view claims of executive power—whether it was in tandem with the legislative branch, and therefore entitled to more deference, or whether it was at odds with Congress’s authority.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett, another key vote, also appeared skeptical of the government’s arguments. “Can you point to any other place in the code or any other time in history where that phrase, ‘to regulate importation,’ has been used?” she asked Sauer early on. The solicitor general did not give a clear answer, and Barrett did not press him further.

Barrett’s other questions also suggested some unease with the scope of what the administration had done. “Is it your contention that every country needed to be tariffed because of threats to the defense and industrial base?” she asked Sauer. “I mean, Spain, France? I could see it with some countries, but explain to me why as many countries needed to be subject to the reciprocal tariff policy.”

Sauer replied that the tariffs were necessary because of the breadth of the claimed emergency. That prompted Justice Sonia Sotomayor to later point out that there was a mismatch between the administration’s actions and stated goals. She noted that the White House had applied a 39 percent tariff on all imports from Switzerland earlier this year, even though the United States had a net positive trade balance with the small Alpine country.

Sotomayor also briefly mentioned the elephant in the room: the freewheeling ways in which Trump has levied tariffs via IEEPA. “The president threatened to impose a 10 percent tax on Canada for an ad it ran on tariffs during the World Series,” she remarked. “He imposed a 40 percent tax on Brazil because its Supreme Court permitted the prosecution of one of its former presidents for criminal activity.

“Does the statute that gives without limit the power to the president to impose this kind of tax—does it require more than the word ‘regulate’?” she rhetorically asked Benjamin Guttman, who argued on behalf of the states.

Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito appeared to be more sympathetic to the Trump administration on broad executive-power grounds. So did Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who wrote a concurring opinion in an unrelated case last term that greatly influenced the Trump administration’s legal strategy in the tariff cases. Kavanaugh cited a move by President Richard Nixon to impose 10 percent tariffs on all imports during an economic downturn as a potential precedent, even though it predated IEEPA’s enactment.

Oral arguments are an imperfect indicator of how the court will decide cases. Majorities can change as the justices write and rewrite their opinions in the weeks and months ahead. Trump has had an astonishing rate of success before the Supreme Court since returning to office in January. This time, however, a majority of the justices appears ready to rule that he went too far.