The Holocaust happened. George Washington was the first president of the United States. Vaccines do not cause autism. Climate change is real. The earth is round. There is no life on the moon. The 2020 election was not rigged.

I have no direct evidence to support any of these claims, but I believe all of them. I do so for one reason: I trust the people who have told me that they are true. I can see for myself that dropped objects fall, that babies cry, and that birds fly. But the number of things I can see for myself is a tiny subset of the number of things that I believe to be true.

For all of us, this is inevitable. It is also highly adaptive. If you believed only those things for which you have direct evidence, you would not be able to function in the world. At the same time, the fact that our beliefs often depend on the claims of trusted others can create a lot of trouble.

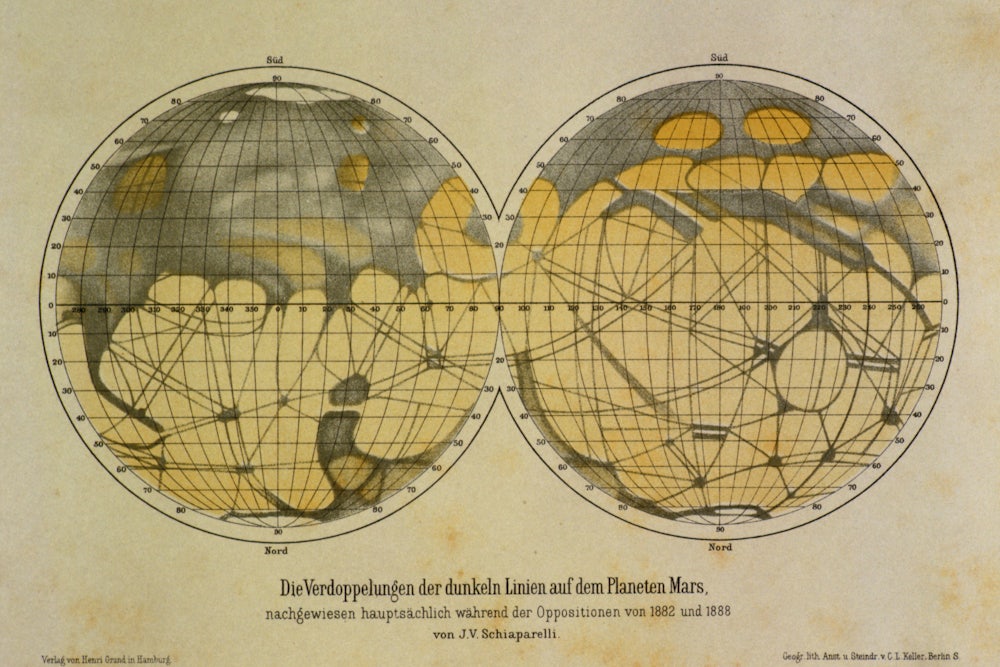

The Martians, David Baron’s riveting exploration of the Mars craze of the late 1800s and early 1900s, is a case study in the formation of unfounded beliefs. The tale begins on August 23, 1877, when the distinguished director of Milan’s Brera Observatory, Giovanni Schiaparelli, took advantage of the fact that Mars was making an unusually close approach to Earth. Schiaparelli maneuvered his telescope in such a way as to get clear looks at Mars, with the goal of producing a detailed map of the planet’s surface. As it happens, Schiaparelli was color-blind, which may, Baron suggests, “have enhanced his perception of shape and contrast.” During the fall and winter of 1877, Schiaparelli made his map. He found dark and light areas, as others had; at the time, these were widely taken to be oceans and continents, and Schiaparelli saw them as such. But he also saw, apparently for the first time, a large number of straight “narrow streaks,” hundreds or even thousands of miles long, “that appeared to connect the seas to one another,” Baron reports. Sometimes the streaks disappeared. Sometimes they were as “strongly marked as a pen line,” Schiaparelli observed. Sometimes they seemed to double; Schiaparelli called that process “gemination.” Incredulously, he asked a colleague: “What could all this mean?”

Because the lines seemed to connect Martian oceans, Schiaparelli referred to them as “canali,” a word that means “channels” in Italian, but that was mistranslated as “canals” in English. In 1882, The Times of London ran a dramatic headline: “Canals On The Planet Mars.” Astronomers around the world tried to confirm Schiaparelli’s dramatic findings. Most of them saw no lines in 1884, 1886, and 1888, when Mars was also close to Earth. But in 1892, astronomers in Peru, California, and France did indeed see the lines. The world was intrigued. Were there living creatures on Mars, constructing canals? The New York Herald wondered: “Are the so-called ‘canals’ really signals which are being exhibited to us, or are they made to connect all the big seas with another?” The Boston Daily Globe speculated: “Who shall say that some day a delegation of Marsonians will not visit the earth.” (The term “Martians” came into widespread use a bit later.)

Percival Lowell, scion of the famous Lowell family (and brother of Lawrence Lowell, later to become president of Harvard), was intrigued. Born in 1855, Lowell was looking for direction in life. He turns out to be the hero, or at least the protagonist, of Baron’s story. He asked the director of Harvard’s Observatory to help him find the “most modern charts or drawings of Mars,” including Schiaparelli’s. He wanted to explore Mars on his own. Having procured an advanced telescope (he had a ton of money), he started to do so in earnest. In his late thirties, he relocated from New England to a pine forest in the Southwest, where the view of Mars would be better.

Before he left, he spoke to an audience in Boston about his plans and Schiaparelli’s fascinating canals. Though he had not seen them himself, he declared that “the most self-evident explanation from the markings themselves is probably the true one; namely, that in them we are looking upon the result of the work of some sort of intelligent beings.” In Arizona, he created his own observatory and hired his own team. But initially he failed to see canals: “To look for the canals with a large instrument in poor air is like trying to read a page of fine print kept dancing before one’s eyes.”

He stared at the planet for hours, hoping that the dancing would stop and that the image would become stable. At times he began to see “faint threads that stretched across the bright surface,” Baron writes, but lamented that he couldn’t be exactly sure they were canals. Before long, however, he became more certain, writing his mother, “The number of canals increases encouragingly,” and eventually seeing them “in profusion.” At one point, he almost gasped at what he saw. Some of the lines were twinned; they looked like railway tracks! Lowell telegrammed the press: “The canals of Mars have begun to double.”

From there, things moved quickly. In the winter of 1895, Lowell returned to Boston, where he delivered four lectures at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He proclaimed that “the telescope presents us with perhaps the most startling discovery of modern times—the so-called canals of Mars.” He urged that the canals were, in fact, evidence of a global irrigation system, designed to bring water to the planet’s inhabitants. He believed that the dark spots were probably settlements, where Martians grew crops. Lowell claimed that what he observed suggested a culture that was far older than our own, and also more advanced. “A mind of no mean order would seem to have presided over the system we see—a mind certainly of considerably more comprehensiveness than that which presides over the various departments of our own public works.”

I am aware that this brief summary might suggest that Lowell’s lectures were wild or preposterous, and that the audience must have thought that he was deluded. But if you read his works in their original form, you will be in for a big surprise. Lowell speaks calmly and patiently. He seems painstaking. He offers some wise statements about belief, noting that “proof is nothing but preponderance of probability.” He offers an impressive number of details about Mars: its relative path around the sun as compared to that of Earth, the length of its year (686.98 days, he reports, compared to 365.26 days for Earth), its size (about 4,215 miles in diameter), its mass (10/94 that of Earth), its average density, and much more. On some of the central details, Lowell’s claims are identical, or nearly so, to current understandings. When Lowell gets to the supposed canals and to the apparent irrigation system, he veers back and forth between confidence, amazement, close attention to detail, and occasional caution. “The canals,” he reports, “are very remarkably attached to one another. Indeed, the manner with which they manage to combine undeviating direction with meetings by the way grows more and more marvelous, the more one studies it.”

Having read some of Lowell’s writings on Mars, I can report a dizzying feeling. Much of the time, the author seems to know exactly what he is talking about, only to disappear into a rabbit hole. If you read him, and then listen to Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. on vaccines, you might see them as twins: intelligent, eloquent, learned, confident, fixated, charismatic, frequently charming, selling snake oil, and living in a fantasy land.

At the time, Lowell’s lectures got a ton of favorable attention. To be sure, some scientists were skeptical. The distinguished astronomer Edward S. Holden, for example, lamented “that the conclusions reached by Mr. Lowell at the end of his work agree remarkably with the facts he set out to prove before his observatory was established at all.” Eventually scientists sorted themselves into two camps: the canalists, led by Lowell, and the anti-canalists, originally led by Holden. Obtaining a more powerful telescope, Lowell made new observations of Mars in both Arizona and Mexico and became even more confident: “I have no doubt that there is life and intelligence on Mars,” he proclaimed. H.G. Wells, the great novelist, was convinced by Lowell. So was Nikola Tesla, the inventor, who believed that he had himself “observed electrical actions” of “planetary origin,” and who added, “Inhabitants of Mars, I believe, are trying to signal the Earth.” Holden thought that was nonsense.

In 1902, opposition to the canalists, and to Lowell in particular, came from an unlikely quarter. Inventors and others were becoming intrigued by optical illusions—by the tricks that the human brain plays on itself. Edward Walter Maunder, a British astronomer, wondered whether Lowell and others were not seeing lines but instead concocting them. “Maunder suspected,” Baron writes, “that the eye and brain, trying to make sense of detail too small to be perceived, might impose straight lines on the chaos.” He thought canals might be just an optical illusion.

To test that hypothesis, he did a study with a number of boys, aged 11 to 15. He wanted to see if he could trick them into seeing canals. To do that, he showed the boys a map of Mars created by either Lowell or Schiaparelli. The map showed actual features of the planet’s surface, but Maunder erased the canals that had been found and marked by the canalists. He asked the boys to try to copy the map as best they could. Sure enough, many of them “saw, and drew, straight lines where none existed,” Baron notes. Maunder claimed that the canalists were like the boys; they saw such lines where there weren’t any. Maunder presented his findings to the British Astronomical Association, most of whose members were persuaded. In response, Lowell ridiculed Maunder. “It is not me who makes lines on Mars, it is the Martians.” Sure, he conceded, “it is quite possible to perceive illusory lines,” but “the whole art of the observer consists in learning to distinguish the true from the false.”

In the face of Maunder’s objections, Lowell continued his work and became even more obsessive. In the first half of 1903, he made no fewer than 372 drawings of Mars. The drawings were elaborate, and each of the many supposed canals had its own name: for example, the Thoth, Amenthes, the Styx, Ulysses, Cyclops, Titan, the Ganges. Aiming to make sense of what he thought he saw, Lowell contended that Martian farmers were fighting to survive on an arid planet, and that they worked hard to shift the flow of water from one agricultural district to another. Lowell claimed that Mars’s waters were being pumped, which meant that Mars had advanced technology and thus a civilization. Maunder responded that Lowell’s theories were “an excursion into fairyland.”

In 1905, Lowell went further. He sent a telegram to the Harvard Observatory, claiming to have photographed the canals of Mars. The New York Sun quoted him: “To-day we can state as positive and final that there are canals on Mars—because the photographs say so, and a photographic negative is nothing if not truthful.” He presented his new photographs, which were indeed of Mars, as unmistakable proof of a Martian civilization. In 1906, he delivered eight lectures in Boston (published in The Century Magazine and later in book form, under the title Mars as the Abode of Life). Emphasizing that he had found proof of life, he insisted, “we have been careful to indulge in no speculation.” Though the photographs were opaque, many people believed him. Surveying the entire year of 1907, The Wall Street Journal published an editorial in which it said that “the most extraordinary event of the twelve months” was “the proof afforded by the astronomical observations of the year that conscious, intelligent human life exists upon the planet Mars.”

Things started to unravel in August 1909, when the American Astronomical Society met in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, at the Yerkes Observatory. Astronomers at the meeting did not see any lines on Lowell’s photographs; they thought that he “was using his imagination.” An American scientist replicated Maunder’s experiments, not with schoolchildren but with experienced astronomers, who drew lines when copying sketches seen from a distance, even though those sketches had no lines. The society’s president, Edward C. Pickering, spoke skeptically about the whole Mars craze. But Lowell responded to his critics vigorously. As Baron puts it, “Few combatants could match his wit and skill.”

He finally met his match, his nemesis, and ultimately his conqueror in Eugène-Michel Antoniadi, an ingenious Greek French astronomer who, as a card-carrying canalist, had drawn his own maps of Mars before the turn of the century. By 1903, Antoniadi described himself as “agnostic,” only to be convinced by Lowell’s 1907 pictures of the red planet, which he called “truly splendid photographic results.” But in late 1909, he engaged Europe’s most powerful telescope. He was able to see Mars pretty clearly—and there were no lines! What Lowell identified as the Amenthes, for example, did not exist at all; where Lowell saw the Thoth, Antoniadi found only “a succession of a few very faint and diffused knots.” He wrote directly to Lowell, with careful and precise drawings showing that there were no canals on Mars. Lowell wrote back, saying that Antoniadi’s telescope had too large an aperture to see what was there. Antoniadi politely disagreed—and proceeded to embark on a vigorous campaign to discredit Lowell.

In that campaign, the brilliant and agile Antoniadi engaged prominent astronomers, insisting that Lowell’s findings “are doomed to become a myth of the past.” He also went public, writing in newspapers and magazines in Greece, France, England, and the United States. In December 1909, astronomers met in London to discuss the controversy. Maunder spoke, repeating his claim that there was no basis for the so-called canals. Antoniadi’s masterful drawings were displayed, and he also had new photographs of the planet, taken through a massive telescope at the Mount Wilson Observatory in California. Those photographs were far bigger, and much clearer, than Lowell’s ever were. They showed the surface of Mars without any straight-line canals, and only with the natural streaks and splotches that Antoniadi had sketched. Antoniadi maintained that the bogus findings emerged from “a disregard of the dangers of pressing too closely the evidence of our senses.”

Responding haughtily to the critics, Lowell once said, “I am very sorry for them.” Another time, he quipped, “The difficulty in establishing the fact that Mars is inhabited lies not in the lack of intelligence on Mars, but rather in the lack of it here.” But his day was over. Schiaparelli himself, now in his mid-seventies, acknowledged that what he had seen back in the 1870s might have been entirely natural. To make things worse, he insisted that the “name ‘canal’ should be avoided.” Lowell continued to make elaborate maps of Mars, but he appeared delusional. He died in 1916, right after a series of bizarre lectures on the canals of Mars and its inhabitants.

Baron is a terrific storyteller, and he has a sensational story to tell, replete with a host of memorable characters (and more than a few romances). As he is keenly aware, the Mars craze cries out for some kind of explanation. Lowell was no con man. He believed what he said. Baron emphasizes “confirmation bias”: people’s tendency to credit evidence that supports their preexisting beliefs, and to dismiss evidence that seems to undermine those beliefs. Lowell certainly showed confirmation bias, big time. But he also suffered from something different. He engaged in “motivated reasoning,” which means that he believed what he wanted to believe.

From the beginning, Lowell really wanted to believe that he saw canals, and that they were clear evidence of intelligent life. His attention to detail, his care, and his obstinacy were all products of motivated reasoning. The same is true of his obsessiveness, which seemed to border on the pathological. In Mars (1895), for example, he lists no fewer than 183 canals, each with its own (weird) name, alongside a notation of the number of times that it appears on one of his drawings. Agathodaemon appears in 127 drawings, while Araxes appears in 93, Daemon in 118, Styx in seven, and Ulysses in 33. It’s quite a system. But there are no canals on Mars! All the while, Lowell was playing with creations of his own imagination.

For a time, Lowell was able to succeed because he helped spur what economists call an “informational cascade,” which occurs when people learn from what others seem to think, and eventually put their own uncertainty or doubts to one side. Confronted with Lowell’s credentials and convictions, many people thought that he must be right, and many of those who might have been doubtful were influenced by the signals sent by the number of trusted people who seemed to think that Lowell could be trusted. When large numbers of people believe a falsehood about anything at all (vaccines, climate change, election fraud), it is often because an informational cascade is at work.

But all this is, I think, missing something important about Lowell, the canalists, and the Mars craze. In much of his writing, and especially in the parts on which he seemed to labor hardest, Lowell seems like a fanatic, and a particular kind of fanatic: a conspiracy theorist. True, he did not point to any conspiracies. But like conspiracy theorists, he promises to open your eyes. He connects a lot of dots (literally). He insists on patterns where they do not exist. He describes a plausible counterfactual world (again literally), with its own internal coherence and logic. He knew more about Mars than almost anyone (even if much of what he knew was false). He was earnest, precise, specific, and attentive to skeptics: “For the canals to come out in all their fineness and geometrical precision, the air must be steady enough to show the markings on the planet’s disk with the clear-cut character of a steel engraving. No one who has not seen the planet thus can pass upon the character of these lines.” He was also intriguing: “That Mars seems to be inhabited is not the last, but the first word on the subject. More important than the mere fact of the existence of living beings there, is the question of what they may be like.” He was seductive, but somehow also nauseating. His writing makes you feel claustrophobic.

The tale of the Mars craze has immense contemporary relevance. There may be no Martians, but right now, science and scientists are under extraordinary pressure, and many researchers are losing funding. Canalists are everywhere, and there are plenty of Percival Lowells out there. Some of them have something like his erudition, charisma, confidence, and sophistication; some do not. Some of them hold positions of authority. They identify patterns. They have radio shows or podcasts. They create informational cascades. They are here to tell you that Barack Obama was not born in the United States, that climate change is not real, that vaccines cause autism, that election fraud is rampant, and that the assassination attempt on Donald Trump was staged. Having connected so many dots, those who hold such theories tend to know a ton—far more than you do. No one is likely to be able to convince them that they are wrong. Like Lowell, they probably feel sorry for those who try.

On the subject of Mars, astronomers found themselves in a state of epistemic turmoil back in the 1890s and 1900s. Fortunately, the stakes were not that high. Lowell did not do much harm. The epistemic turmoil in which we now find ourselves is much more acute and far more dangerous. Some people sincerely believe damaging falsehoods. Others do not believe them, but are happy to push them for fame, profit, or power. Who are the modern-day equivalents of Eugène-Michel Antoniadi, willing and able to show what is true? And how can we get sufficient numbers of people to pay attention to them?