Midway through the journey of her life, Olivia Nuzzi found herself in Malibu, for she had wandered from the straightforward path. In exile from the East Coast, where she had held a plum gig with New York, she awoke on the West, with a plum gig at Vanity Fair, doing hard time as “West Coast editor.” With The Divine Comedy in one hand and The King James Bible in the other—or at least, on display when the Times writer came for the profile—she set out to document her descent. Themes were close at hand. Dante, he wrote about the inferno. Fire, you dig? Well, guess what California’s got? Lousy with it.

The mismatches between reality and reality as described in American Canto began long before the book was released. To recount a fall from grace, it helps to have actually fallen from grace, and on publication day the author was still, somehow, in the upper echelon of her industry. The circumstances that caused her to skip town—to wit: an affair with RFK Jr., then a presidential candidate she had been assigned to profile—would be humiliating to anyone, certainly. But writing as if she was living in hell seems a little unfair to both Malibu and Vanity Fair. Which isn’t the magazine it used to be, but what is, these days? American Canto is a book about personal decline that ends in hitting rock top.

Here the thing gets stranger still, because when the much-celebrated writer got a chance to write at greater length than ever before about the Trump era, the result was an actual fall from grace, with Nuzzi garnering unimpressed reviews and Vanity Fair cutting ties with her (amid a series of revelations from her ex-fiancé Ryan Lizza). This set of events has precipitated altogether too much discourse. There are the claims and counterclaims of the primary participants. There’s second-order discourse about what the whole thing says about some other problem—the influencer-fication of journalism, maybe. Most of that is true enough.

There’s third-order discourse, where people discuss the discussion. “The titanic sexual shaming of a woman, Monica Lewinsky-style,” posted Caitlin Flanagan on X. “No one’s going to be proud of this coverage in 20 years.” It got weirder. “When I look at her I see a little girl, like my daughter,” Lisa Taddeo wrote in Air Mail, adding that “the attempted patriarchal mass murder of this woman’s career” is a “freaksome lynching.”

I’m a little older than Nuzzi. I think good writing—clear thinking—matters. Not much, but a little! This is a minority position, I am learning. If Nuzzi came away from the last decade with useful insight for us, it would not excuse her ethical lapses, but it would be a point in her favor. If she didn’t—if, say, she came face to face with various incarnations of American evil over a decade and not only failed to recognize them as evil but came away with little to tell us—it would tend to sharpen questions about what her defenders are defending, what our industry rewards, and the purpose, if any, of writing in the Trump era.

I have to admit something that surprised me: Parts of this book work. They work conditionally, and not in a way intended by the author, but they work. The sections of American Canto that concern people other than the author herself and RFK Jr. don’t work at all. In this book, other people are always flat and seen through a gauzy screen, and the prose is composed substantially of filler—long portions of transcripts republished whole, republished tweets from accounts like “Bimbopilled,” song lyrics and poetry, historical digressions that go nowhere. On the occasions when Nuzzi lets her mind show, something snaps into place. It’s good for the same reasons the first part is bad.

Before we get there, we have to talk about the Didion thing.

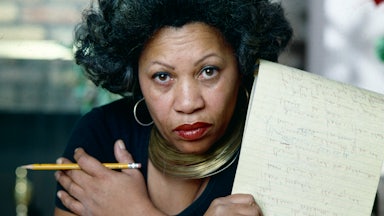

Ordinarily it would be an act of cruelty to compare a writer’s first book to Joan Didion’s work, but Nuzzi summoned the specter of Didion in the build-up to publication. A California book, about fire and entropy and social sickness and the East as seen from the West, a mix of memoir and essays and reportage. The promotional art for American Canto in both Vanity Fair and a glowing Times profile features Nuzzi in her white Mustang, sunglasses, California chic, which inevitably recalls the black-and-white pictures of Didion with her Stingray.

What’s in the text is actually much weirder. The book’s California sections imitate not only Didion’s themes and interests but her specific writerly tics and constructions down to the sentence level. If you happen to buy this book, read it alongside “Quiet Days in Malibu,” the last piece from The White Album. Some of the similarities could be coincidental. Didion’s piece sketches the lifeguards at Zuma Beach, and she clearly likes the way the word looks and sounds, using it over and over. Nuzzi refers back throughout the book to “the little house at Zuma.” Didion loved proper place names, and making lists of them (a tendency Mary McCarthy made much fun of in her review of Didion’s Democracy), and she whips ’em out in “Quiet Days” to draw a parallel between the lifeguards and generals on a front: “All quiet at Leo. Situation normal at Surfrider.” Nuzzi does too, some of the same ones, and for the same reason: “Ball of fire at Point Dume. Clear. Boney Ridge, the San Gabriels, the Topa Topas.”

In American Canto, there’s a certain tick-tock patter that will feel familiar, and also a certain habit of addressing the reader to clear up meanings and definitions. “I mean to tell you as best I can,” starts one paragraph. The next: “I mean to tell you of the canyon.” Two more that way. You may hear a certain resonance in Nuzzi’s description of a childhood home flanked by “hydrangeas and forsythias and tomato plants.” Didion liked playing with negation and repetition, and there it is in the description of RFK’s brain parasite, “the worm that was not a worm.”

Didion loved repetition, loved building long stretches of metronymic prose that break, for effect, in long, sweeping, propulsive sentences. She also loved using the full names of her subjects, rather than last names or pronouns. Here, from the second page of Canto, one of those propulsive sentences:

I knew about beauty pageants because of JonBenét Ramsey, and I was frightened by beauty pageants because of JonBenét Ramsey, because she was the first girl through whom I learned that if you are beautiful you may get killed, and once you are killed you will become the property of the country, and the country will resurrect you so that you can be killed again and again in ecstatic detail on the national altar of television; JonBenét Ramsey said that if you are beautiful you may get killed in service to your country.

If you haven’t caught it, she’s drawing a parallel between herself and her troubles as a beautiful person and Ramsey, and she gives herself permission to draw the connection because of a kind of numerology. “In 1996, the year that Donald Trump acquired the Miss Universe Pageant, I turned three, and JonBenét Ramsey, who was six, was murdered.” Three years later, when she was six, she saw Donald Trump’s car in traffic.

Didion’s techniques have a purpose. Nearly all of her writing had as its target sloppy thinking, self-deception, delusion. Her prose style was the scalpel she used to cleave the real from the unreal. The repetition, the specificity, the remove from her subjects, created a sense of absolute, dispassionate precision. When she’s writing about herself, this precision leavens the anxiety she feels and provides a useful tension. When she’s free to observe other people she’s not emotionally invested in—say, Michael Dukakis or Newt Gingrich—her prose, and her thinking and analysis, is as clear as a mountain spring.

In American Canto, these techniques are exactly the wrong choice—they spotlight what is actually occurring on the page, which is imprecise prose reflecting unclear thinking. This is true from the jump. In the brief introduction, Nuzzi writes that this is not “a book about the president or even about politics.” A few pages later, though, she writes that what “happened between me and the Politician,” which is to say RFK Jr., is in fact the same thing that “happened between the country and the president. I cannot talk about one without the other.”

This sets up the expectation that some meaningful insight into both men is forthcoming. But Nuzzi writes of the Trump era that “events lost context. Words lost meaning.” Sure, but isn’t the point of the writer to separate true from false and discern meaning? The sections about Trump consist too often of long, uninterrupted quotes taken from already published reportage and summaries of events a knowledgeable reader will already know.

Nuzzi has a habit of bending reality to the more cinematic, sentimental version of it. At the beginning, she recalls the trauma she felt from witnessing the day during Donald Trump’s trial when “the boy who missed his mother and could no longer bear to be here doused himself in gasoline and lit a match. When I learned what burning flesh smells like. Strange and sweet.” During a TV appearance later she says she could taste him in her mouth, a horrible thing to imagine. But you may remember that the “boy who missed his mother” was a 37-year-old schizophrenic man who believed information about an imminent fascist takeover was being transmitted to him through classic Simpsons episodes. He was, in a way, a symbol of our time, but not the one that the author wanted to use.

The imprecision in the book’s prose and description of reality is greatly exacerbated by the mystifying decision not to use proper names for figures with whom Nuzzi personally interacted. The reader is supposed to juggle descriptions of the Personality, the President, the Politician, and the Performer, among dozens of others. Not all are so vague, thankfully—there’s the “South African Tech Billionaire” and “the digital everything-company billionaire” and “the War Hero, the senior senator from Arizona”—but others will make the reader confused. When she refers to a businessman, is it the same one as before? I can guess who the “MAGA General” is, but who is the “failed candidate”?

Does it even matter? In a world where words have lost all meaning, what’s the point of words? The sense conveyed by this portion of the book is that the author doesn’t believe they have any—doesn’t believe in much of anything—even though the book is being marketed as an attempt to explain everything.

Meaning is occasionally gestured to, though most often it is left to hang. Nuzzi finds it significant that she was born on January 6. Hey, that’s kinda funny, a reader might think, but for the author this and other conjoined coincidences recall the Ouroboros: “Strange symmetry. Circular. On this humid night, a last gasp as the tail met the jaw. I did not yet grasp this.” She writes that she found her respect for RFK Jr. swell when he dropped a writerly insight about Trump. “I always thought of him as a novel: hundreds of lies that amount to one big truth.” A good line, one that Nuzzi writes filled her with jealousy and longing. But the natural question is: What’s the one big truth? We sail right on by.

There are long sections of this book Nuzzi clearly does care about, and understood in the proper register, they’re strangely compelling. The register in which to absorb American Canto is the one in which you’d read Pale Fire, whose verbose and unreliable narrator, Charles Kinbote, draws us slowly into his deepening, complex madness. Read it this way, and a lot of what might irritate you otherwise will click into place.

This sounds, I’m sure, like an attempt to be cruel. But I mean it earnestly. Nuzzi succeeds in letting us into her mind and communicates how she came to make the mistakes she did, and these portions, at least, are worth reading not because they’re true but because they aren’t. They’re carefully written to obscure as much as they reveal; written defensively. When she first addresses the scandal, she writes in the passive voice that “a monumental fuckup had collided my private life with the public interest.”

But this is a kind of sincerity also. She is admirably frank that she is still primarily motivated by resentments and perceived slights rather than a desire for atonement and forgiveness. “People ask me now about anger. About my lack of it. How? How could I not be enraged?” This is not, of course, the question most people have. She still views Kennedy as a put-upon outsider rather than what he has subsequently revealed himself to be. This is true in both her personal sense of him and her analysis of the man as a political actor—“a collision of conspiracy and error that made it so that he could not win,” she writes, though this was hardly the problem with Kennedy’s bid. She valorized him, and to some extent still does, as a man who made all decisions by thinking through “what would be best for the country. I was sure he could do that, I said, because I trusted him that much.”

The tragedy here, that what Kennedy has done is to wreck American science and health in a way that will take generations to recover, is never addressed. She tangled with a monster and survived, and doesn’t quite seem to have gotten it. The betrayal he carried out, which results in him earning the name the Politician, is to sell out Nuzzi. “I never did think of him, not until much later, and then for reasons that came as a shock, as a politician.” As a journalist, this is a permanently disqualifying lapse of judgment. But it’s good character development.

This gives the book a certain horror-movie undercurrent, as Nuzzi keeps rendering judgments, even from her present position, that the reader suspects are upside-down and missing the key thing. She writes that Kennedy thought it “would be fun” if the two went to Mar-a-Lago at the same time. Nuzzi thinks Trump will clock the affair. She shut her eyes “tightly, as if it might un-reveal the revelation that he did not appreciate how sophisticated an animal he was dealing with,” even though she says a few pages before that Kennedy was perfectly clear-eyed about Trump. “It was not the sort of information the Politician should have wanted the president to have,” she says.

The reader may suspect, in fact, that Kennedy, clearly loving the power imbalance, would have enjoyed seeing her squirm—and would not have minded Trump knowing. It only gets worse from here. Later, she says Kennedy was “not good in a crisis” and “did not know much about how the media worked,” as she explains why his impulse was to lie and slander her when their affair was reported in the press. The discernment that is the essayist’s only valuable skill is gone.

When the thing blows up, Nuzzi is furious at everyone who brought the lapse of judgment to light. The editor who learns the truth—“the man for whom I worked”—was trying to “trap” her. “I had never before lied to him,” Nuzzi says. Then she lies. But of course, she has been lying for a long time now, advocating for the presidential campaign of a person she did not reveal she was intimately involved with. She lambastes those who told the editor as betrayers: She even uses the book to litigate an unrelated grievance with the magazine’s creative director.

From here the madness deepens. “What occurred in private was supposed to be private, and it had not been my choice that it ceased to remain so, nor that a corporate media outfit with a political reputation to uphold had been spooked into participating in what I considered a siege of hyper-domestic terror,” she says. She attempts to make the muddled case that the terror is the result of liberal persecution for her criticism of Joe Biden.

She gets in the white Mustang and drives west, and becomes convinced drones are stalking her. She meditates on how the waiters at D.C. restaurants are most likely spies. The shadows around her grow longer, her alienation deepens. Her connection to reality fractures further and, at the very end, she declares, watching another drone hover over the beach, that “I do not recall what a plane ought to look like in the night sky, whether it should move fast or slow, if it should appear to remain in one place for very long, if it should ever move in circles or up and down,” before declaring that “nobody cares anymore.”

The impulse is to say: Of course you know what a plane does. But maybe not? The last line is another jagged fracturing. The drone is sending a message from God, she writes, and she is unsure whether it is meant to “offer reassurance or to issue a threat.”

In the Times profile that preceded the book, Nuzzi said she wrote American Canto to “complete a thought.” The easy joke: just one? But I, too, feel how hard it is to complete a thought at the moment—to think clearly about anything. Whether it’s the microplastics or the general deadening sense of the world around us or the comforting feel of the phone in my hand, it is a constant struggle. American Canto is the work of a disordered mind in anguish, terribly raw. To the extent that she has put this calamitous state of mind on the page, the prose version of flipping between X and Instagram over and over, alternating between dread and self-delusion, Nuzzi has, in spite of herself, produced an artifact of the age.