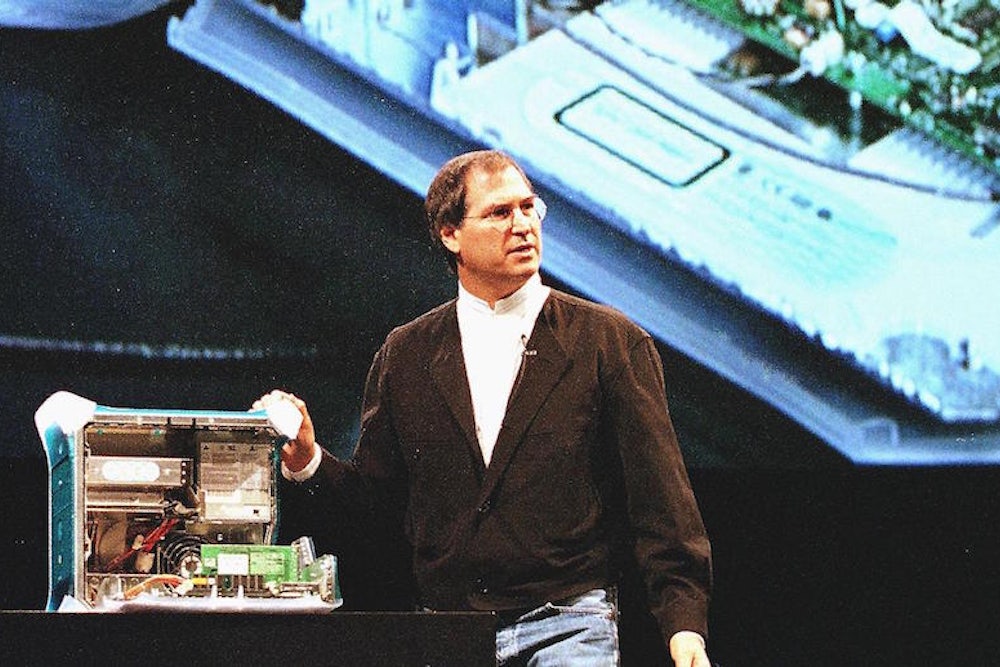

“It’s like, five minutes before a launch, everybody goes to a bar and gets drunk and tells me what they really think.” It is 1998, and Apple is about to launch the iMac desktop computer to a rapturous reception, but CEO Steve Jobs is under assault. Jobs (Michael Fassbender) has just left the scene of a brutal fight with his fellow Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak (Seth Rogen), who tells him, “Your products are better than you are, brother.” Danny Boyle’s tense, disputatious film Steve Jobs (with a walking-and-talking extravaganza of a script by Aaron Sorkin) does indeed revolve around the people in Jobs’s life—confidants, colleagues, employees—telling him what they think.

Sometimes his enemies are duplicitous colleagues and dishonest journalists; sometimes they take the shape of 5-year-old girls. “My dad named the computer after me,” his daughter notes before the launch of the Lisa, and Jobs, who has resolutely denied his paternity, cannot prevent himself from bickering with her, too: “I’m not your…”

Jobs suggests that he is simply too busy, too consumed with the cosmic significance of the computer revolution he leads, to be nice. “It’s not binary,” Wozniak tells him. “You can be decent and gifted at the same time.” But when you are responsible, as Jobs argues, for one of the two most significant developments of the century (only the Allied victory in World War II is deemed its equal), then the perpetual alienation of friends and colleagues is not without purpose.

Jobs never explains, and never apologizes. Instead, he diagnoses his bugs in the only dialect he is truly comfortable in: that of technology. “Why did you say you weren’t my father?” Lisa, now a Harvard student, wonders. “I’m poorly made,” Jobs responds.

A spate of recent films, as well as novels like Dave Eggers’s The Circle and Joshua Cohen’s Book of Numbers, and television series like Silicon Valley and Halt and Catch Fire, have made computer wizards and masters of technology alluring and terrifying.

This shift toward depicting technology’s “poorly made” tycoons began in earnest with David Fincher’s The Social Network (2010), also written by Sorkin, in which Jesse Eisenberg’s hoodie-clad Harvard student Mark Zuckerberg swipes the idea for the social-networking site that would become Facebook, not only from the entitled jerks who don't know what to do with it, but from his best friend and cofounder, Eduardo Saverin. The Social Network craftily ended by reducing Zuckerberg to the status of one of Facebook’s users, searching for his ex-girlfriend on the site, pushing send on a friend request, and obsessively refreshing the page, hoping for the buzz of contact made.

The tech CEOs of subsequent films were often cruel, surface charm stretched tightly over a vast reserve of unthinking callousness. Even the hagiographic Steve Jobs movie—a predecessor to Jobs from 2013 starring Ashton Kutcher—showed some of the Apple founder’s dark side. Amidst the montages of travel to India, rolling wheat, and other pseudo-inspirational effluvium come flashes of Jobs’ titanic anger. Jobs’s legendary focus and determination transform even trusted allies into enemies when pushed hard enough. “I would say I hope you choke,” he shouts at Wozniak (Josh Gad) during one squabble, “but that burrito’s going to kill you either way.” Another employee is fired mid-meeting for his insufficient devotion to the burning issue of fonts for the new Macintosh.

The most disturbing moment in the 2013 movie comes when Jobs kicks his girlfriend Chrisann out of the house after she tells him she is pregnant. The stressed-out Jobs, consumed by the fate of Apple, has no bandwidth available for his unborn child: “You can’t do this to me right now … I’m sorry you have a problem, but it’s not happening to me.” “This company will not make shit anymore,” the new Jobs announces upon his return to Apple.

These films, shows and books reflect a fear of technology from both ends of the moral spectrum: because of its inhumanity, and because of its all-too-human applications. “If you knew the trouble I had getting an A.I. to read and duplicate facial expressions,” Nathan (Oscar Isaac) in Ex Machina says to his underling Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson) as they tour the laboratory of his remote Alaskan compound. As CEO of Blue Book, a Google-like search engine, Nathan issues Caleb with a series of mental, physical, and emotional challenges, while his employee tests his latest creation, a near-sentient, artificially intelligent being named Ava (Alicia Vikander). Nathan, it turns out, has cracked the puzzle by turning on every microphone and camera in the world and collecting the data. Caleb is simultaneously impressed and dismayed: “You hacked the world’s cellphones?”

Nathan is a genius and a bro, a friend and an overlord, a scientific savant and something of a perv. The more we are impressed by his seemingly limitless skills, the less we are taken by his humanity. His near-miraculous unleashing of true artificial intelligence is inextricably intertwined with a willingness to poke into the most private digital reaches of his employees (and, by extension, his customers), and a certain fetishism regarding the robots, who are themselves all disconcertingly sexual. The wizard is a creep.

The cinematic tech wizard is always all-powerful in both his skills and his resources; possessing as much knowledge as he (and it is always a he) does, he naturally possesses a proportionate share of the world’s riches, as well. (“A million dollars isn’t cool. You know what’s cool? A billion dollars.”) The one tech savant we have actually seen in person onscreen, however, hardly matches the stereotype. When we first see Edward Snowden in Laura Poitras’s Citizenfour (2014), we are struck by his ordinariness. Here is a standard-issue cubicle rat, a bland-looking white-collar twentysomething puttering with his laptop.

But Snowden is remarkable not only for his access to an extraordinary stream of information, but for his disinterested desire to divest himself of it. “I don’t want to be the person making the decisions,” he tells the journalists he has brought in to assist him in promulgating the story of the NSA’s mass surveillance of American citizens. The developments in Citizenfour unfold with the pace of a spy thriller, even as Poitras elides Snowden's questionable decision to flee for the undemocratic safety of Vladimir Putin's Russia. In the course of a week, Edward Snowden goes from an anonymous government employee to a man who can see his face on the side of a Hong Kong building out his hotel window. Snowden is exposing the dark side of the utopian Internet espoused by the likes of Nathan and Jobs, in which frictionless communication is revealed to be frictionless surveillance as well.