In the second Democratic debate, Hillary Clinton deflected a question about her electability with an observation that could apply to pretty much any issue in the presidential race. She noted “there are some differences among” the Democratic candidates, but those differences “pale compared to what’s happening on the Republican side.” Climate change was one of the fundamental divides that she cited. In an exclusive interview last month, Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta told me, “Politics is largely about friction. And I view this as a place of high friction with the Republican candidates today.”

“High friction” understates things. When it comes to climate, there are two entirely different political conversations taking place in the primaries. On the Democratic side, Clinton, Bernie Sanders, and Martin O’Malley are delivering the kind of earnest energy debate the climate movement has longed for, each with a plan for building on President Barack Obama’s executive actions. Yet every Republican in contention has vowed to undo or weaken Obama’s most significant policy, placing pollution caps on power plants under the Clean Power Plan. In the process of scaling back domestic action, the Republicans are also promising to handicap the first signs of global progress on the issue in 25 years.

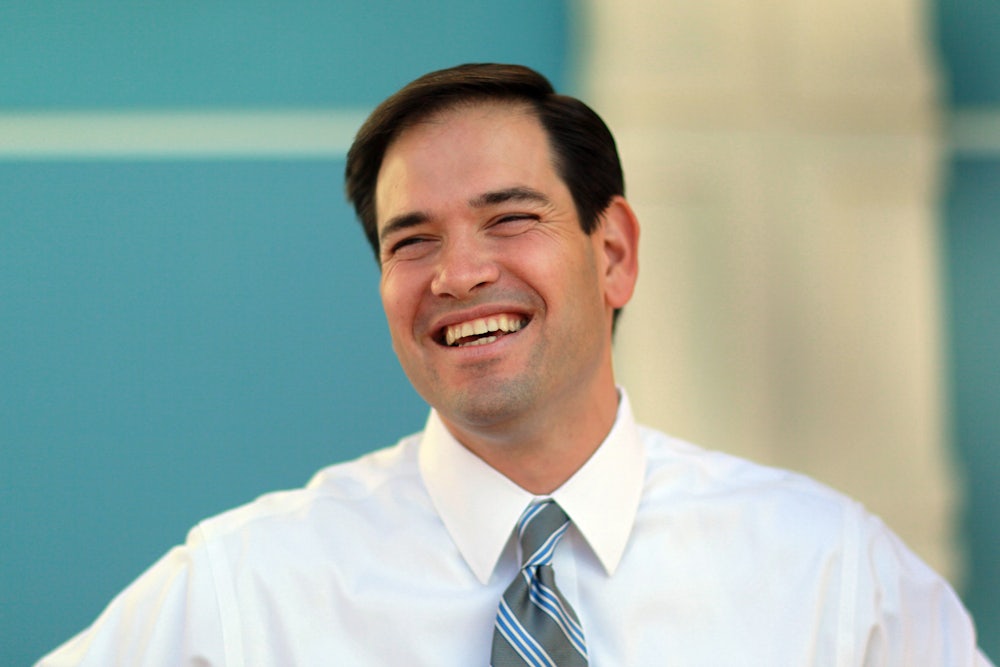

“The Clean Power [Plan], we ought to repeal that and—and start over on that,” Jeb Bush—who is one of the few GOP candidates who’ve openly acknowledged man’s role in warming the globe—said in the most recent debate. Marco Rubio argued that the CPP would wreck the economy and also inevitably fail: “We are not going to make America a harder place to create jobs in order to pursue policies that will do absolutely nothing, nothing to change our climate, to change our weather.” Back in August, Ted Cruz staked himself out clearly for repealing Obama’s plan: “The President’s lawless and radical attempt to destabilize the nation’s energy system is flatly unconstitutional.” Ben Carson and Donald Trump, meanwhile, have joined the Texas senator in flatly rejecting the evidence that manmade climate change is real.

The Republicans’ willful ignorance will drag down the climate debate when the general election rolls around. Which is unfortunate, because Democrats have had a substantive conversation that goes beyond easy calls to promote clean energy. In their first debate, Clinton, Sanders, and O’Malley all mentioned climate change twice in their opening statements. O’Malley has proposed raising fees for leasing public lands and rejecting offshore drilling, and he took a memorable jab in the first debate at the Obama administration’s much-criticized “all-the-above” embrace of fossil fuels: “We did not land a man on the moon with an all-of-the-above strategy.” Sanders has gone further, insisting twice in debates that climate change is America’s greatest national security threat and introducing a bill to halt all future fossil fuel development on federal lands. All the Democrats, including Clinton, have promised to tackle Obama’s worst legacy on climate change, digging up more oil and coal.

But that heady debate will largely be over when general election season rolls around, as it turns into one about science believers versus science deniers. Environmentalists have made some of the greatest gains of any interest group in the final years of the Obama administration, benefiting—at long last—from a president willing to use his executive powers to break a political stalemate on the issue.

The options for a Democratic successor to do more would be limited, especially with Republicans likely to continue controlling Congress. But environmentalists—really, all Americans concerned about the planet’s future—have a lot to lose in 2016, as Republicans are poised to unravel everything Obama has put in place. That doesn’t include just include the Clean Power Plan, but methane regulations for natural gas, land and ocean conservation, clean-water reforms, solar and wind development, and air-pollution regulations.

Ideally, the 2016 election would be over how we can solve the most pressing problem of the world’s future. Instead, the Democrats and Republicans are headed for an argument over whether we should even try to ensure the world is livable in the very long-term. But behind that gloomy prospect, you can spot progress in both parties’ internal climate debates—though you have to squint to see it in the GOP. Democrats are breaking new political ground, while Republicans are facing new pressures to acknowledge reality. And if Democrats succeed in making climate a vital issue that helps them win in 2016, Republicans will be forced to contend with some awkward arguments they’d much rather continue to ignore.

Democrats have the easier job of selling their plan for climate change to the 69 percent of Americans who think greenhouse gasses should be regulated. For starters, they’re willing to talk about the problem.

That hasn’t always been the case. In 2012, Obama never highlighted the contrast between his vision and Republicans’ on environment and energy, nor did he go into detail on his second-term plans to pursue executive action. A disaffected environmental community took to calling out both parties’ “climate silence.” There was only one memorable spotlight on climate in that election: Mitt Romney mocked Obama in his convention speech for pledging to “slow the rise of the oceans,” and Obama at his own convention indirectly responded with the line, “Climate change is not a hoax.”

Clinton could have adopted a similar playbook for 2016, letting the GOP create their caricatures while largely ignoring climate herself on the campaign trail. Instead, she’s used climate policy proposals to reassure doubtful Democrats of her progressive bona fides during the primary. And if she reaches the general election, according to Podesta, she plans to hammer Republicans for being out of touch with American voters on the subject. “I think that unlike past campaigns, including the Obama campaigns, this will be a front-and-center issue,” he told me.

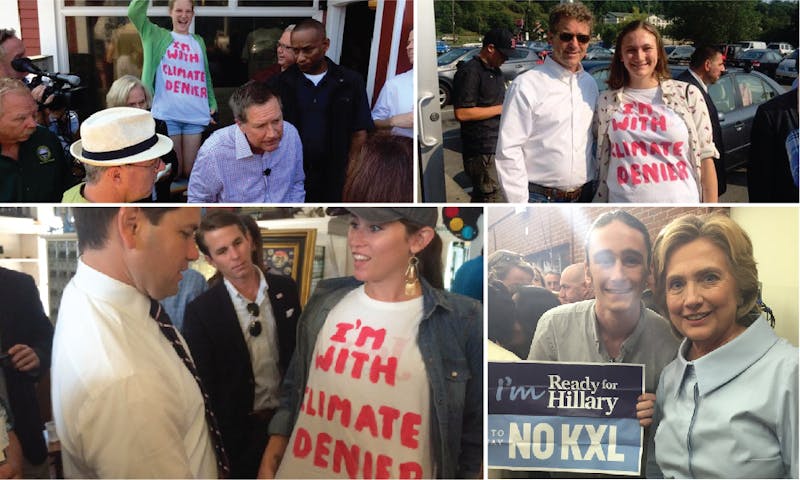

Could climate change, which has long ranked low on the list of voters’ priorities, be a winning issue next November? A growing portion of the electorate is worried about climate change—a Pew poll released in November found that 45 percent of voters today it a serious threat, up from 37 percent in 2010. Clinton is already reminding voters of GOP denialism, saying recently in New Hampshire, “Now we have candidates like Ted Cruz who say climate change is not science. That can be pretty dispiriting, but it can also be galvanizing.”

Obama has done much of the heavy lifting to make climate a top 2016 topic. His slew of executive actions have infuriated Republicans, along with his negotiations for a deal in Paris to curb carbon emissions. That’s upped the ante for all the Democratic candidates, particularly Clinton, to make specific pledges to push harder and further on renewable energy, greenhouse-gas reduction, and fossil fuel extraction. But so has pressure from activists and the movement’s new deep-pocketed donor, California billionaire Tom Steyer; one of the largest single donors in the 2014 midterms, Steyer has promised to elevate environmental demands in 2016 by pledging even more money.

All this has pushed Clinton leftward. One of the first white papers her campaign released was for ambitious solar development, to get to 33 percent of renewables by 2027. Bernie Sanders’s gains have certainly added to that pressure: as a longtime opponent of both Keystone XL and Arctic drilling, he helped nudge Clinton past her long silence on those two issues; this fall, Clinton came forward against both projects as Sanders climbed in the polls.

The candidates and activists continue to push Clinton: Lately, she faced questions about how far she is willing to go to keep fossil fuels in the ground by scaling back leasing on federal property. These lands contain 450 billion tons of pollution—the equivalent of a year of burning coal at 118,000 power plants. However, companies cost taxpayers damages that range from 20 to 200 times as much as they pay in fees averaging around $1 for a ton of coal. Reforming those rates would help close the $500 billion taxpayers spend on coal and oil. While activists argue the next president should end off-shore and on-land leases entirely, Clinton might have reached her limit on this issue: For now, she’s only promised “additional fees and royalties from fossil fuel extraction.”

Activists say that isn’t enough—but some perspective is in order: Just four years ago, Obama was touting increases in drilling and mining as one of his first-term accomplishments.

If Democrats win, what will environmentalists get for all their hard work? Another advocate in the Oval Office who can carry out the work that’s left to be done at the executive level on carbon and methane. They may not see Clinton move any further left on climate policy in this campaign—yet where she stands is far and away beyond where any Democrat has been going into a general election. Their bigger reward would be what they’d have narrowly missed: A Republican president poised to gamble with billions of people’s lives and well-being around the world.

For a brief moment earlier this year, it looked like two Republican contenders, Jeb Bush and Rand Paul, might be ready to recognize climate change as a problem worth solving. Bush moderated his past positions and openly acknowledged carbon pollution, which was enough to earn him a passing score from scientists for his public statements on climate. Paul was one of 15 congressional Republicans in January to acknowledge that humans contribute to climate change. Then the crazy primary season took hold, and the entire field lurched to the right, as Paul demonstrated earlier this month by firmly aligning himself with the deniers in the fourth GOP debate. The only two candidates who think that government ought to play some role in solving climate change can’t get to 1 percent in polling; neither George Pataki nor Lindsey Graham even made the recent undercard debate.

Because the electorate generally does consider planetary warming to be a problem, GOP candidates must constantly search for new excuses to ignore it. This year, we’re hearing deniers like Cruz calling global warming a religion. Others prefer to argue that policies will lead to skyrocketing costs for consumers—or, in a related argument, that they’ll hurt America’s competition with China. Bush and Rubio, well aware of the risks of appearing too out of touch with American voters in case they win the nomination, have subtly shifted from outright denial to saying the government should get out of the way when it comes to solving the problem. “Ultimately, there’s going to be a person in a garage somewhere that’s going to come up with a disruptive technology that’s going to solve these problems,” he said in July, “and I think markets need to be respected in this regard.” In other words, the private market alone can fix the issue.

The Republican Party writ large may may be inching in the right direction. Some conservatives tired of the party’s approach have offered donations to pro-climate candidates; newcomer donors include North Carolina businessman Jay Faison, who’s pledged $175 million to candidates who support conservative solutions for climate change. Some of the main business constituencies that Republicans court endorse climate action; that increasingly includes Wall Street and even some utilities. Meanwhile, more Republicans at state and local levels are planning seriously for combatting climate change. But at the national level, Tea Party denialism still wins out.

This capitulation to grassroots pressure means that the Republican nominee next year will come into the general election already having pledged to reverse much of the progress Obama—and by extension, the world—can make by January 2017. Rubio, for instance, is not the most extreme Republican candidate on climate. But if he wins, he will have promised to delay if not permanently reverse the Clean Power Plan, pull the U.S. out of the long-fought-for international climate agreement, and hamstring the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to curb carbon emissions. Clean energy might still grow domestically under a Republican president, but without government subsidies or regulations to force fossil-fuel extractors to reflect their true social cost, it would be far too little to put the world on a manageable path of warming.

By arguing the government should play no role on climate policy, the Republicans have left little room to moderate their positions in the general election. This won’t be another election plagued by climate silence, but there still won’t be much of a debate between the parties. Clinton, if nominated, will be focused on showing just what the country will gamble its future on if it puts a Republican in charge. As a bonus, she won’t have to make it up.

But it is conceivable, as Podesta believes, that climate becomes a defining issue in 2016—and that it gives a clear edge to Clinton or another Democratic nominee. Nothing would do more to push Republicans away from denialism and into a realistic debate about solving climate change. For now, though, electing a Republican—any Republican—is as good as saying America welcomes a world of 4 degrees Celsius or more of warming. That is double the level at which scientists and world leaders think civilization can adapt.

Correction: A previous version of this story said Tom Steyer is from Colorado. He lives in California.