Nothing seemed unusual when the Supreme Court released its first decision of the current term last November. It was only one month into the court’s calendar, and the brief, unanimous opinion by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in Hamer v. Neighborhood Housing Services of Chicago was fairly typical of the court’s non-blockbuster fare.

No other opinions in argued cases were released for the rest of November, or all of December. The rest of the court’s work went on as usual: petitions were granted, motions were denied, weekly conferences were held. But in the cases it had heard—the ones that received full briefings and oral arguments—there was only silence.

Things first seemed amiss when the justices returned from their winter break in the second week of January. Still the court had produced no opinions in the cases it had heard months earlier, as it often did after holidays past. Adam Feldman, a lawyer who runs the blog Empirical SCOTUS, had noted in December that not since 1868 had the court waited as late as January to issue its second opinion of a term. That year, the opinion arrived on January 11. This year, not until January 22.

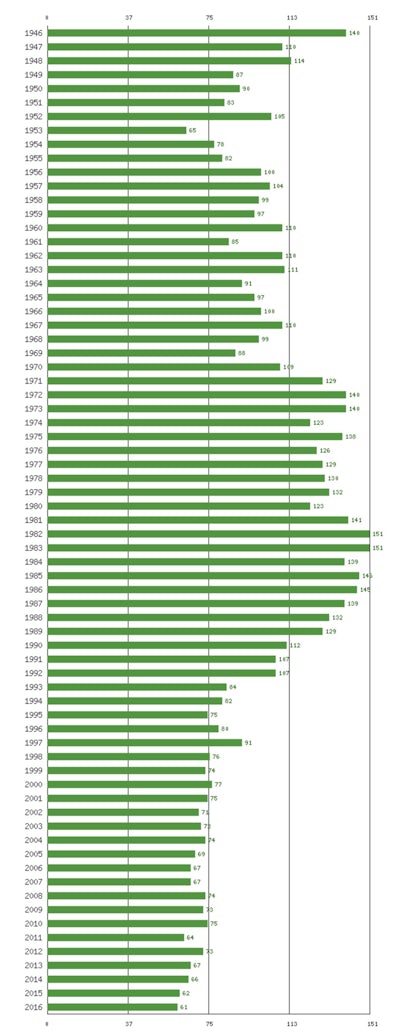

The court has picked up its pace only slightly since then: It issued two decisions earlier this week, including a notable ruling that limits deportations of non-citizens convicted of state crimes, bringing its total so far up to 22. Even then, the 2017-2018 term is one of the slowest terms on record for publishing decisions, according to Feldman, a statistical expert on the court. “Through the end of March 2018, the court released the fewest signed majority opinions of any term since [John] Roberts was appointed chief justice [in 2005],” Feldman said. “It is also the lowest output through March of a term at least since 1946.”

And unless there’s a deluge of opinions in the next few weeks, this term may end up being one of the court’s slowest, ever.

The Supreme Court’s languid pace comes after two tumultuous years. Antonin Scalia’s sudden death in February 2016 upended the justices’ work during the 2015-2016 term and resulted in multiple deadlocked cases. With only eight members, the court became equally divided between its conservative and liberal wings, making it harder to reach majorities in high-profile cases.

Republican senators refused to consider Merrick Garland, President Barack Obama’s nominee to replace Scalia, thereby leaving the court short-staffed and evenly split during most of the 2016-2017 term, too. President Donald Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch to the vacancy on January 31. By the time the Senate confirmed him in April, most of the court’s work had wrapped up for the term.

The court kicked off the 2017-2018 term at full strength, but the infusion of fresh blood hasn’t translated into either faster opinions or more of them. What kind of internal dynamics are driving the slowdown isn’t clear: The Supreme Court rivals only special counsel Robert Mueller’s office when it comes to secrecy in Washington. Nonetheless, a few theories have taken root.

Stephen Vladeck, a University of Texas law professor who argued before the court in January, prefaced his comments by warning, “This is wild speculation.” But he suggested that a major factor may be the kinds of cases that the court is considering this year. Sitting on the court’s docket are hot-button disputes over the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering, a major digital-privacy case that could shape the Fourth Amendment’s future, a showdown between LGBT rights and religious-liberty claims, and Trump’s infamous travel ban.

“It’s not at all unusual for the justices to be at loggerheads over these divisive cases,” Vladeck explained, “but one wonders if at least some of these disputes (especially partisan gerrymandering) have not only provoked back-and-forth drafts of vitriolic opinions, but also efforts by justices to broker compromises that might, in turn, require the court to go back to square one.”

The partisan-gerrymandering cases in particular—there are two—appear to be causing major headaches for the court this term. The court heard oral arguments in Gill v. Whitford, a potentially landmark case on the constitutionality of Wisconsin’s warped state legislative maps, on October 3. As of this week, it’s one of the earliest argued cases from this term that’s still undecided.

The justices subsequently gathered in March to hear oral arguments in Benisek v. Lamone, which centers on an aggressively redrawn congressional district in Maryland. At those oral arguments, it became apparent that while the justices largely agreed that partisan gerrymandering needed to be reined in, they hadn’t yet reached any common ground on how to do it.

It’s not just opinions that are running behind. Other matters before the Supreme Court have also been delayed, Vladeck said. In Azar v. Garza, the Trump administration has petitioned the court to toss out a lower federal court’s ruling that allowed an undocumented immigrant minor to obtain an abortion while in federal custody. (Courts allow abortion cases to proceed even after the pregnancy ends because the appellate process is longer than the human gestation period.) The justices began weighing the administration’s request in December, but haven’t taken any action.

The court also took months to deliberate over whether to take up Hidalgo v. Arizona, the latest case to question whether the death penalty should be abolished. The court first considered it in a November 1 conference, but ultimately didn’t decline until March 19. Justice Stephen Breyer, joined by justices Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan, issued only a brief statement accompanying the decision that left the door open to future challenges.

Individual personalities may also be playing a role. “My sense is that there is an increased focus on consensus under Roberts that wasn’t there under [former Chief Justice William] Rehnquist and possibly not even during Roberts first few years as chief,” Feldman said, pointing to the slowing pace throughout Roberts’s tenure. “This could delay the process, especially in cases with close voting splits.” Also, Gorsuch’s arrival—or perhaps more importantly, Scalia’s absence—may have upset the court’s routine.

Another factor in the court’s slow pace is that the justices have been taking up fewer cases in recent years. The justices receive thousands of petitions for review each year, but take up only a small percentage of them for full consideration. “The lowest number of signed majority opinions in a term since 1946 was 61 in 2016, followed by 62 in 2015, and 64 in 2011,” Feldman said. “We are going to end up around those numbers this term as well.”

That’s a sharp decline from the 1983-1984 term, the court’s postwar high-water mark for output, when it heard 153 cases. But taking up fewer cases isn’t necessarily a bad thing, Feldman noted. “Perhaps this is related to the justices aging, and the justices might say that they are spending more time poring over each case and writing the opinions,” he said. “I think it’s more likely that the output is related to the court adjusting to this lighter workload to better space their work out across the term.”

As the court nears the end of its term in June, observers will get a clearer picture of the divisions behind the delays that have shaped an unusual and historically slow term. Conclusive answers will have to wait a few decades longer. “Whatever the cause,” Vladeck said, “we may not find out for generations—until the current justices’ internal papers are released.”