For nearly half a century, an air of inevitability has clung to the decline of the American labor movement. As union density has fallen to near 10 percent and strike activity has reached historic lows, labor has often fumbled in its response to political attacks. Since 2012, five states have passed anti-union “right-to-work” laws, after campaigns funded lavishly by right-wing billionaires. In June, the Supreme Court dealt another blow, ruling in Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees that public employees cannot be required to pay fees to a union. With this decision, public-sector unions are now set to go the way of the once-great industrial unions—institutions that underwrote the creation of middle-class wealth and crystallized a still-powerful image of American prosperity.

In the rearview mirror, the three decades after World War II, when the expanded labor rights regime of the New Deal was at its strongest, increasingly look like what the historian Jefferson Cowie has called a “great exception.” For most of American history, politicians and courts have given employers nearly unrestricted control over the terms of work, and they have offered the resources of the state—above all, the military and police—to enforce those terms. And even when laws regulating the length of the working day and establishing safety requirements were passed, courts frequently overturned them. Workers’ failure to make much headway by the early twentieth century led scholars, beginning with the German sociologist Werner Sombart, to argue that the United States was just different from Europe: It lacked a class-bound medieval past, it had an individualistic ethos, and its workers were too diverse to organize effectively.

This way of seeing American labor is undermined, however, by the historical record: There was, in fact, a militant labor movement in the United States, one that sometimes even worked with vibrant socialist and communist parties. While professional and racial differences split some groups, others overcame those divisions and collectively faced down violent repression from their employers, state governments, and even the general public. Striking workers at the Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel and Iron Company in 1914 met with machine guns, fired into their encampment by a private strike-breaking firm and the National Guard; two years earlier, textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, had contended not only with state and private security forces, but also with Harvard students who were released from their exams to fight the strike.

Recalling these stories today is important, Erik Loomis argues in A History of America in Ten Strikes, because even though the workplace is still a “site where people struggle for power,” the memory of workers who fought for basic rights has largely disappeared, he observes, “from our collective sense of ourselves.” Every leap forward in American labor history—from safety regulations to the eight-hour day—has been achieved by mass mobilization of workers. But if at least some, and often many, Americans have always been ready to take militant action for a better life, why have their successes proved so limited and fragile?

Throughout the history Loomis traces, American workers have tended to apply pressure directly on their employers, rather than on the political system. By the 1830s, machinists, coal-heavers, and carpenters were striking against wage cuts and long working days. The famous “Lowell Girls” of the Massachusetts textile industry, whose neat living quarters and employer-sponsored education were supposed to illustrate how America would avoid the bitter class conflict typical of Europe, soon grew to see factory work as a kind of oppression incompatible with the American ideals they cherished. They organized work stoppages, and one of their number, Sarah Bagley, would in 1844 found the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association, which pressured the Massachusetts government to hold hearings on working conditions.

The fight against long working days remained a central demand for over half a century, and was a major factor in the rise of the Knights of Labor. Founded in 1869, America’s first major national labor organization rallied hundreds of thousands of workers around the demand of an eight-hour day. They believed that the power of highly concentrated capital was undermining the principles of a decentralized republic that prized self-government. Peaceful arbitration between employers and workers, they hoped, could restore something of the democratic balance that had existed between the many small producers in the founding era. The Knights’ brilliant leader, Terence Powderly, shied away from challenging corporate power and worked to avoid strikes, pursuing negotiation with employers instead.

Powderly underestimated the power of the new corporate behemoths to respond violently to the slightest hint of labor organizing. Local leaders and workers took a less reserved approach, and in 1886 nearly half a million of them participated in the wave of strikes that culminated in the Haymarket Massacre in Chicago. Amid several tense days, in which worker protest alternated with police violence, as many as six workers were killed and an unknown figure threw a bomb into a group of police officers as revenge. The backlash against labor in the press and the general public broke one of the most powerful strikes in American history, and brought the downfall of the Knights of Labor.

The following decades would decide the direction of the labor movement up to today. These years saw the emergence of the American Federation of Labor, founded in 1886 after the Haymarket affair and still part of one of the largest forces in labor in the United States. Under Samuel Gompers, the AFL championed the protection of craft workers, such as carpenters, tailors, and cigar makers, some of whose skills were being devalued by the rise of mass production. AFL craft workers’ contempt for unskilled wage-laborers often combined with anti-immigrant racism to form a nativist unionism, centered on protecting members’ own elite status. Concerned that focusing on political change would lead to laws that could be overturned by courts, the AFL devoted itself to securing union contracts in the workplace.

The AFL’s long hostility to immigrants and industrial workers—who were more and more clearly the future of the labor movement—left the field wide open to the Industrial Workers of the World, which would display a special flair for dramatic strikes and bold political demands. The IWW was the first labor organization to mount a direct challenge to capitalism, deploying a slate of tactics that went beyond the AFL’s narrow bargaining. “Wobblies,” as they were known, gave radical speeches in public places and, when the police shut them down, crusaded against violations of the First Amendment; they roused workers against their miserable living quarters and scams that required them to pay for a job. The 1912 strike in Lawrence showcased IWW ingenuity, as striking textile workers sent their children away on trains to be housed by sympathizers of the strike in other cities. After police beat a group of women and children attempting to board a train, sensational congressional hearings ensued and Lawrence workers won all their demands.

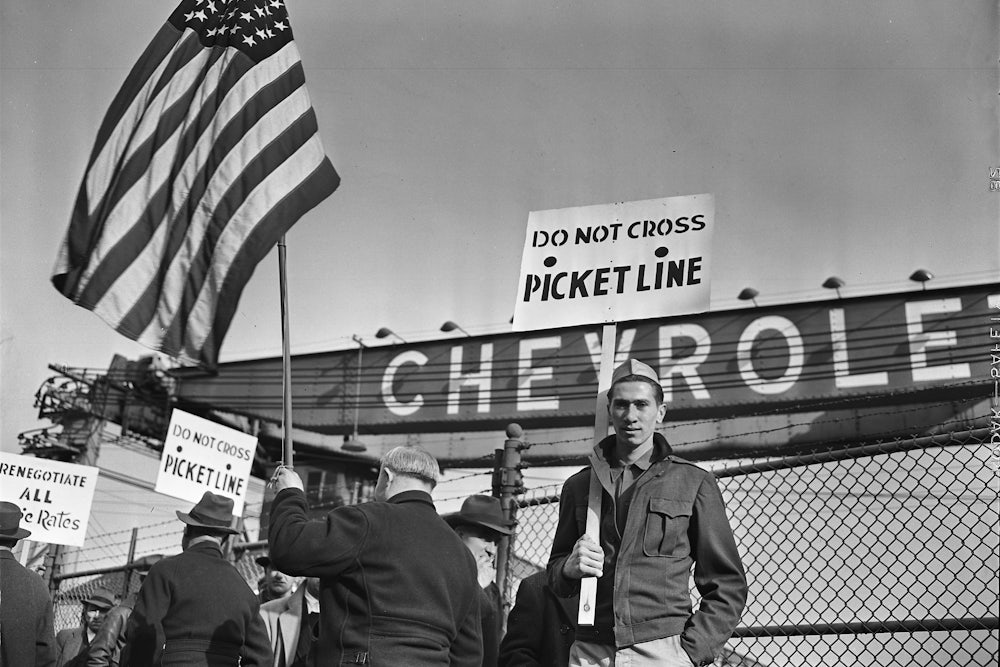

The IWW could have set a different course for labor. As Loomis points out, the group was more inclusive than those that preceded it. But the Wobblies had their own weaknesses, including a “love affair with violent rhetoric” and failure to build institutions that could protect their victories. That would have to wait for the Congress of Industrial Organizations, a group of industrial unions within the AFL that broke away in 1937. The CIO would orchestrate some of the major victories of American labor’s peak decade, the 1930s, as radical unions like the United Auto Workers won historic strikes against industrial employers such as General Motors and Chrysler, paving the way for the mass unionization of the auto, rubber, steel, and electricity industries, among others.

Their breakthrough came in the famous 1937 “sit-down strike” in Flint, Michigan, when workers occupied a General Motors factory and fought back police repression with rocks and water hoses. Despite multiple court orders to vacate the employer’s property, one bearing a potentially ruinous $15 million fine, the UAW refused to end the occupation. Using other factories to create diversions for the police, the UAW escalated the strike just as it began to waver and secured the exclusive right to bargain with GM for a contract. It was a critical turning point for labor, but even this was only a promise to negotiate—and a weak one considering the still-disorderly organization of the incipient UAW. With worker enthusiasm fluctuating and recession setting in later in 1937, the CIO’s victories were tentative and fragile.

For all the courage of the unionists, Loomis reminds us that even this victory was only possible because the political winds had changed: The New Deal had arrived, granting workers the right to collectively bargain with their employers, and Michigan’s progressive governor Frank Murphy refused to order the National Guard to crush to the strike. “There is simply no evidence from American history that unions can succeed if the government and employers combine to crush them,” he writes. “All the other factors are secondary: the structure of a union, how democratic it is, how radical its leaders or the rank-and-file are, their tactics.” The ultimate success or failure of worker militancy depends on the reaction of the state.

If this is true, it is something of a surprise that politics mostly remains in the background in Loomis’s book, with occasional mentions of key court decisions and the individual political figures who intervened (or more rarely, didn’t) in specific strikes. While he outlines the histories of the most important labor organizations, he addresses crucial adjacent institutions like the Socialist and Communist parties, and even the Democratic Party, only in passing, which makes it difficult to get a handle on the whole fate of labor as a political force in American life. With a focus primarily on the events of rank-and-file work stoppages, Loomis occasionally gives the impression that labor activism happens primarily on the shop floor, and that it extends little further into the political arena than in electing allies to office.

There were clearly moments when sympathetic elected officials tipped the scales toward workers. When Davis Waite, the Populist governor of Colorado, resisted demands to send the National Guard to break a gold miners’ strike in 1894, the strikers successfully stood down an effort to add two hours to their day for the same pay. Loomis contrasts this success with the Pullman strike the same year, when 150,000 railway workers at the Pullman Car Company walked off the job in sympathy with aggrieved coworkers. This time the state was not supportive. The U.S. attorney general, a former railroad industry lawyer, ordered federal attorneys to issue an injunction against the union. President Grover Cleveland then called in the military. Thirteen strikers were killed and 57 wounded. If workers picked their political allies, big business could do the same much more easily.

The major example of workers benefiting from the support of a political candidate, of course, came with FDR and the New Deal. While Roosevelt’s rapprochement with labor was driven more by electoral ambitions than political ideals, the groundswell of popular support for activism—as well as business opposition to the New Deal—hardened his determination to pass pro-labor legislation. Chief among these was the Wagner Act of 1935, which created the National Labor Relations Board, established collective bargaining rights, and legally restricted employers’ campaigns against unions for the first time. Although many of FDR’s labor policies were designed to make unions less radical by creating a bureaucratic structure around labor relations, they sent surges of energy through the labor movement and emboldened even more militant worker actions.

But as Loomis makes abundantly clear, “electing allies to office” was at best only ever a temporary solution, because those allies often failed to keep their end of the bargain and, when they did, their work was rapidly undone by their successors. Already in the late ’30s, a recession halted much of the CIO’s organizing, Roosevelt’s favor had shifted back to employers, and the congressional alliance between Republicans and Southern Democrats reversed the direction of labor policy. Labor representatives and social-democratic reformers were shut out of war-economy decision-making, which gave wide latitude to big business. In 1947, the Taft-Harley Act severely limited labor activism by outlawing sympathy strikes and closed shops, and by allowing employers to spread anti-union messages in the workplace. As Cold War paranoia mounted, unions were forced to purge Communists from their ranks, which in many cases meant losing some of their best organizers.

Loomis refuses to romanticize this period or the labor movement it produced. When the UAW signed a five-year contract with General Motors in the “Treaty of Detroit” in 1950, one of America’s most radical unions agreed to moderate its demands: UAW members got wage increases and excellent benefits, but surrendered their hope of having more of a say in the production process and in national industrial policy. They also agreed not to strike for the duration of the contract, allowing GM a period of calm and efficient production. “By committing to working with companies to promote smooth operations and tamp down rank-and-file activism,” Loomis writes, unions “acquiesced to the end of political radicalism.” As Fortune magazine summed up, GM “paid a billion for peace” but in the end still “got a bargain.”

The result, as many New Left radicals would later argue, was an institutionally more conservative labor movement that would often prove hostile to more radical forces that might have renewed it from within. In an era when labor leaders should have set about consolidating the gains of industrial unions and expanding them through new and growing sectors of the economy, the movement settled into a somewhat one-sided relationship with the Democrats in Washington. Over this same period, the business class expanded its anti-union efforts from lobbying to a wide-ranging political blitzkrieg, underwriting an anti-labor cultural turn through a dizzying array of grassroots organizations and university research centers.

American radicals and labor activists have long identified the need for a labor party, but have repeatedly failed to form one. Though there was some interaction between the IWW and Eugene Debs’s wing of the Socialist Party in the early twentieth century, the two ended up keeping their distance, as the Wobblies pursued militant, anti-institutional unionism and the socialists kept a narrow focus on elections. The Communist Party, founded in 1919, took a more expansive view of both political and labor organizing, but settled into a posture of compromise during the Popular Front era, only to find itself persecuted almost out of existence with the rise of postwar anti-Communism.

The late ’30s might have been the best moment for the creation of a labor party, when unions were rapidly building power. Yet several forces blocked its path. Roosevelt’s unprecedentedly pro-worker policies brought the signature issues of more radical parties into the mainstream, making those parties less relevant to many voters. The more conservative AFL experienced a growth spurt as it collaborated with employers, preparing employer-friendly contracts, to preempt more radical CIO organizing. The AFL’s sabotage put the CIO on the defensive, forcing it to cling desperately to its alliance with the Democratic Party. (The two groups wouldn’t merge to form the AFL-CIO until 1955.) A small coalition of the country’s more radical unions returned once again to the idea of founding a labor party in 1996, but failed to attract a broad enough base of support from more powerful unions, which preferred their existing relationship with the Democratic establishment.

It would be premature to call for a labor party today, but the forces that might eventually put workers on a stronger footing are starting to emerge. Candidates aligned with the Democratic Socialists of America have begun to unseat complacent members of Democratic machines at the municipal, state, and national levels. Unions, too, are looking for more radical politicians: Last year, the AFL-CIO announced it would stop giving its endorsement to “the lesser of two evils” in political races, and even proposed considering third-party politics. At the grass roots, teachers’ strikes in Chicago, West Virginia, and elsewhere have connected the demands of educators to a powerful defense of the public sector and community interests as a whole.

In the current hostile legal climate, it is likely that strikes like these will again become an important vehicle for the labor movement. They will demonstrate the thrill of collective power to a new generation of workers, many of whom have never known work to be anything other than a disempowering and underpaid grind. But just as important are the broader project and organizations behind the strikes.

What Loomis’s book perhaps does best is remind us that the promise of the labor movement, despite its many failures and compromises, has always been to make everyday life more democratic. American labor militancy has always been about more than pay, with workers seeking respect and fairness in the workplace. As Loomis writes, the successes of the CIO in the ’30s meant more than “a few extra dollars in the pocket after getting a union contract”—they also gave workers a say in society for the first time. If a twenty-first-century labor movement can hope to succeed, it will need to revive that promise, and show sidelined, disaffected Americans that democracy begins at work.