For the past two months, the bulk of the Republican Party and the conservative movement has pushed unhinged conspiracy theories about election fraud. Most of them stood back and stood by while President Donald Trump constantly lied about the outcome, or while he pressured state officials into overturning their election results. While Trump raged and ranted to his supporters about imagined crimes, their supposedly corrupt perpetrators, and the phantasmal harms they would somehow inflict if not stopped, they either actively supported the president or humored him.

Now, after the attack on the Capitol last week, a growing number of Republicans have come to a hard conclusion: Democrats should be nicer to them. You know, for unity and bipartisanship and civil peace.

“Impeaching the president with just 12 days left will only divide our country more,” Kevin McCarthy, the House Republican leader, said in a statement on Friday. “I’ve reached out to President-elect Biden today [and] plan to speak to him about how we must work together to lower the temperature [and] unite the country to solve America’s challenges.”

It’s hard to fathom the gall it takes to issue such a statement less than 48 hours after voting to throw out lawful, legitimate electoral votes for Biden, as McCarthy himself did. It’s worth noting that McCarthy isn’t resistant to accountability for every politician. In the mid-2010s, he played a key role in spinning up the Benghazi consulate attack into a smear campaign against Hillary Clinton in the hopes of sabotaging her presidential campaign. What Republicans like McCarthy are calling for is not unity—not a genuine reconciliation or an honest peace. What they are demanding is impunity.

McCarthy is far from alone among Republicans who’ve belatedly adopted this rhetoric. Ronna McDaniel, the chair of the Republican National Committee, said on Monday that the country “desperately needs to heal and unify” and warned that impeachment proceedings “will only divide us further.” There was no reckoning in McDaniel’s statement with her own efforts to undermine public confidence in the election. Politico reported in December that McDaniel played a key role in a brief plot to not certify some results in Michigan and swing the state to Trump, even as she reportedly told associates that no significant voter fraud had taken place in the state.

“Those calling for impeachment or invoking the 25th Amendment in response to President Trump’s rhetoric this week are themselves engaging in intemperate and inflammatory language and calling for action that is equally irresponsible and could well incite further violence,” Texas Representative Kevin Brady wrote on Twitter. Brady did not vote against the Electoral College count last week. But he was among the members of Congress who joined a friend-of-the-court brief in December that asked the Supreme Court to throw out the results in Pennsylvania and other key states that went for Biden.

Another signatory on that brief was Colorado Representative Ken Buck, who asked Biden “in the spirit of healing and fidelity to the Constitution” to ask Pelosi to halt the push toward impeachment. In the letter on Saturday, Buck touted the fact that he opposed blocking Biden’s electoral votes last week, eliding his earlier participation in a scheme to overturn the results. He also said it would be as “unnecessary as it is inflammatory,” criticized the haste with which it would be conducted, and said Pelosi should “set aside this partisan effort immediately.”

What makes Buck’s comments all the more striking is that he’s supported unconventional approaches to impeachment in the past. During Trump’s first impeachment saga last February, he suggested that Congress should instead open impeachment proceedings against then-candidate Biden, drawing upon the Trumpworld smear that he had acted inappropriately in Ukraine. “[Former] Vice President Biden could be impeached now,” Buck said at the time. “There’s no reason that you have to only impeach someone that is in office. You can hold the hearings. You can gather the evidence. You can move forward.”

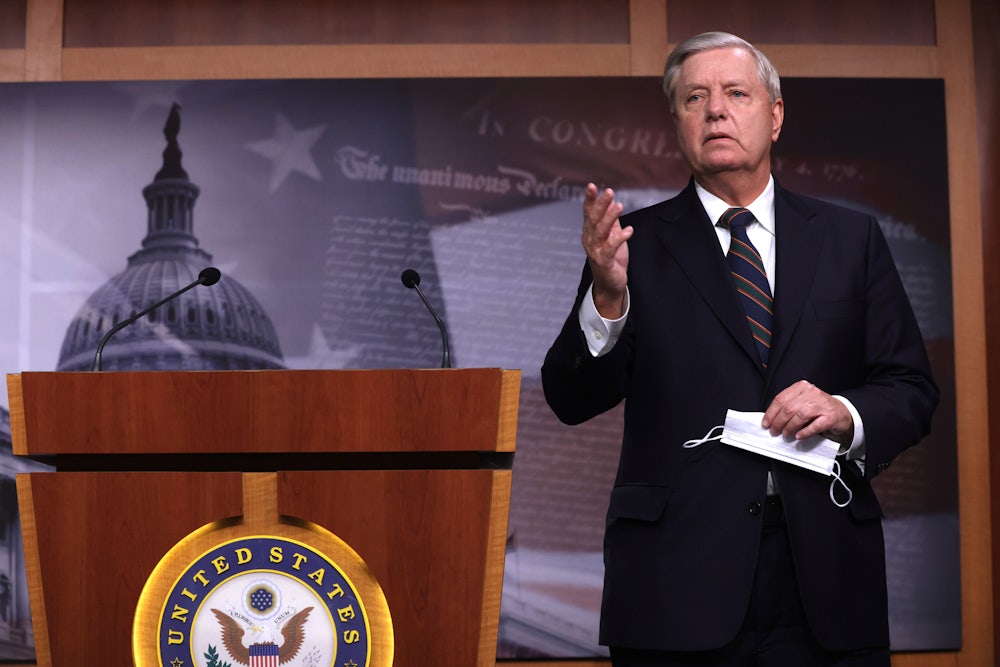

Even Republicans who didn’t openly join Trump’s campaign against the election outcome have endeavored to shield him from consequences. “Biden has a historic opportunity to unify America behind the sentiment that our political divisions have gone too far,” Florida Senator Marco Rubio said on Sunday. “But instead he decided to promote the left’s efforts to use this terrible national tragedy to try and crush conservatives or anyone not anti-Trump enough.” Others called for Biden to focus on the future instead of the past. “In light of President Trump’s Thursday statement pledging an orderly transfer of power and calling for healing in our nation, a second impeachment will do far more harm than good,” South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham wrote on Monday. “It is past time for all of us to try to heal our country and move forward. Impeachment would be a major step backward.”

None of these statements are substantive defenses of Trump’s actions or an explanation of why he doesn’t deserve to be impeached for them. McCarthy and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, the two leading Republicans in Congress, have both indicated that Trump is ultimately responsible for at least some of last week’s violence. The Senate may not even need to hear from witnesses if there’s a trial. Trump used Twitter and public rallies to incite the mob against Congress, and all but two of the senators who’ll be at his trial were there to witness the bruised fruits of his violent labor.

So why the sudden demand for reconciliation? It’s possible that some of these Republicans were genuinely alarmed by last week’s violence and now fear that Trump’s supporters will try to retaliate against Congress if he’s impeached. They may also be concerned that Trump will take some sort of extreme action in the last few days of his presidency if he feels cornered by Congress. These are both valid concerns, though most Republicans have, through their own actions, made it impossible to assess whether any of their stated convictions are sincerely held. But they nevertheless speak to the fundamental unsuitability of the man who sits in the White House. They are not defenses against Trump’s impeachment or removal; they underscore its necessity.

It’s more likely that these calls for unity—an ambiguous word in this usage—are little more than a partisan deflection. More than a few Republican members of Congress likely know that what Trump did is not just grievously wrong but also impeachable conduct. If Biden had responded to Trump’s election lawsuits by telling an antifa-laden crowd that the Supreme Court was going to steal the country from them, told them to fight back, and then refused to intervene when they ransacked the justices’ chambers, is there any doubt what Republicans would be doing or demanding right now?

Why is Trump so special? It’s certainly not because the president has shown any sort of repentance for his actions. Trump’s video statement last week did not include an apology for his rhetoric, or even an acknowledgment that his voter-fraud lies had contributed to the attack. He initially refused to order flags to be lowered to half-staff at federal buildings for the Capitol Police officer who was killed by Trump supporters during the attack, and he has not yet issued any statement of condolences to the man’s family. According to The New York Times, he even told associates last week that he regretted issuing the video statement where he supported the transition of power and condemned the violence. This is not a man who is deserving of mercy.

Republican lawmakers know all of this. But they also know that Trump’s power isn’t completely broken. Even if he doesn’t run for president again in four years, he’ll retain considerable influence over the party and its candidates. And so most Republican lawmakers oppose any consequences for his actions because they fear being on the wrong side of them. If they were willing to place the good of the republic ahead of their own self-interest, they would see why Trump’s impeachment—and a measure of accountability for his actions—is a moral and civic necessity. Then again, if most Republicans in Congress could see that, none of this would have happened in the first place.