State courts! Of all the institutions of American government, they might receive the least attention relative to their impact on day-to-day life. State courts are where most criminal trials are held, most civil lawsuits are filed, and most of the legal business of American society is actually conducted. They range from the hyperspecialized water courts of the American West to the Delaware Court of Chancery, which quirkily decides an outsize share of corporate law cases for most of the country’s largest companies.

Over the years, many states have experimented with reforming these courts in various ways. Some have experimented with nonpartisan elections for judges; others rely on impartial commissions to select nominees. But an increasing number of state lawmakers, almost always Republicans, are pushing back—and pushing the envelope. The result is an unambiguous effort to make state courts less independent and more partisan than they have ever been.

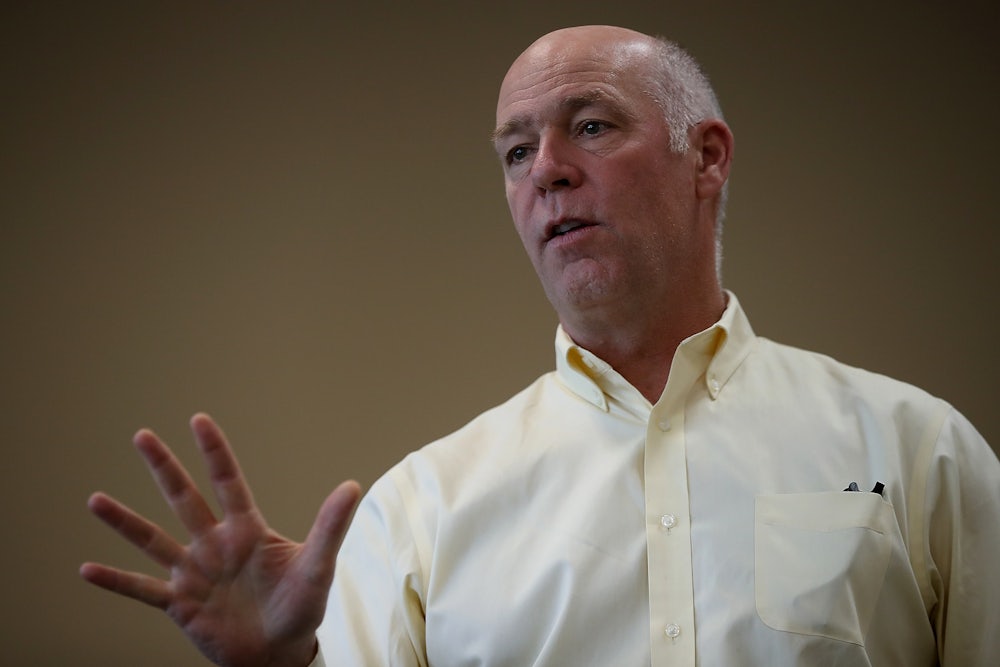

In Montana, Governor Greg Gianforte signed a bill this week that abolished an independent commission that nominates judges for seats on state district courts and the Montana Supreme Court. The new law transfers that power to the governor, who can now fill any vacancies, subject to approval by the state Senate. The Great Falls Tribune reported that Lieutenant Governor Kristen Juras had criticized the commission because some members had donated to Democratic candidates.

Gianforte himself also framed the change in the rhetoric more often seen in federal judicial battles. “When judicial vacancies occur, I will appoint well-qualified judges who will protect and uphold the Constitution and who will interpret laws, not make them from the bench,” he said in a statement. “I am committed to appointing judges transparently, providing for robust public input, and ensuring judges have a diversity of legal background and subject matter expertise.”

The Montana law isn’t an isolated move. The Brennan Center for Justice found that, in 2020, lawmakers in 17 states had introduced nearly 50 bills that would “diminish the role or independence of state courts.” Some state legislatures introduced measures that would increase partisan influence in the judicial selection process. Lawmakers in Alabama and Colorado introduced bills that would constrain judges’ discretion on death penalty cases and religious freedom disputes, respectively. Other bills sought to change how elected judges run for office and introduce incentives for them to get more partisan.

Almost all of these bills are coming from Republican lawmakers who are frustrated by the direction of their state courts. Perhaps the best example comes from Pennsylvania. Thanks to a 2019 ruling by the Supreme Court, federal courts can no longer hear cases that seek to overturn legislative maps for partisan gerrymandering. But some state courts have since filled the void. A few years ago, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court struck down the state’s congressional map, which was so gerrymandered toward Republicans that Democrats would regularly win roughly half of the statewide vote while only capturing roughly one-third of the seats. The state high court then drew a new map to be used until the redistricting process begins again later this year.

Pennsylvania Republicans responded to the ruling by looking for ways to assert their influence over the state courts. Donald Trump’s harsh criticism of Pennsylvania and its state Supreme Court during the legal battles surrounding the 2020 election has only added fuel to the fire. State GOP lawmakers introduced a constitutional amendment earlier this year that would replace the statewide election of state Supreme Court judges with elections by judicial district, which the Republican-led legislature would draw. In essence, it would enable a state legislature that relied on partisan gerrymandering for years to gerrymander the court that made it stop.

What are the risks of a politicized state judiciary? Look no further than Wisconsin, where a flood of campaign spending in judicial elections transformed the state’s widely respected Supreme Court into a theater for partisan brawling. Last year alone saw the Badger State get bogged down in unusually bitter disputes, driven by its state Supreme Court, over Covid-19 restrictions and state election practices. In Florida, state GOP lawmakers are so confident that Governor Ron DeSantis’s latest choices for the Florida Supreme Court will overrule precedents that hindered GOP policy goals that they have begun passing laws that outright contradict those precedents.

Why have these moves against state courts’ independence gained so much ground in recent years? First, and most simply, GOP state lawmakers have the means to make them. State constitutions are easier to revise and alter than their federal counterpart. Federal courts, and especially the Supreme Court, enjoy a level of social and cultural support that makes it hard for Congress to impose even mild structural changes. (Note, for instance, that there hasn’t been a new federal judgeship created since 1990.) As for opportunity, many red-leaning states are now effectively under one-party rule, especially after the last few election cycles.

And when it comes to motive, few are more powerful than the desire to implement long-standing conservative policy goals. State courts, like their federal counterparts, play a significant role in influencing how America is governed. As I noted in 2018, state constitutions and state courts could provide an alternative means to achieve liberal policy goals now that conservatives are firmly entrenched throughout the federal judiciary. More recently, The Appeal’s Daniel Nichanian highlighted a ruling by Washington’s state Supreme Court on drug-possession laws to show that potential. If courts can play that role for liberal causes, conservatives have a vested interest in hindering and influencing them.

The good news is that these right-wing efforts largely haven’t succeeded so far. The Brennan Center’s report on bills introduced in 2020 noted that only one of them actually became law. Some managed to make it to committee hearings or a floor vote, but most of the proposals died a quiet death. Earlier this month, the attempt in Pennsylvania to gerrymander its state courts also fell apart. That’s a good sign for the integrity and independence of state judiciaries. But it’s still easy to see which way the trend in changing state judiciaries is going—and harder to see where it might end.