The title of Joseph Darda’s new book, How White Men Won the Culture Wars, may land awkwardly for weary followers of recursive debates over cancel culture, wokeness, and the like. The loudest and most visible partisans in these battles are aggrieved white men, insisting that they’re scapegoats in unhinged identity-driven witch hunts and eagerly putting themselves forward as martyrs in ugly confrontations over free speech. How is it, then, that this demographic emerged as the victors of the modern American culture wars and managed to leverage that success into ongoing, ever-renewable plaints of grievance?

The answer, Darda argues in this original and persuasive revisionist study, lies in the overlap between the post-1960s culture wars and the legacy of an actual war: the American debacle in Vietnam. The United States withdrew in defeat from Vietnam in 1975—a fraught moment as well for the American political economy, coinciding with the landmark civil rights and feminist uprisings that convulsed the country as many American soldiers served overseas. Returning Vietnam vets mimicked the rhetoric and strategies of the era’s homegrown protest movements while developing a powerful narrative of abandonment and trauma to convey their own sense of disaffection. And in spite of the heavily nonwhite and working-class makeup of the conscript army in Vietnam, the dominant image of the Vietnam vet became a white, middle-class one.

This curious work of cultural alchemy came about thanks to the convergence of several other post–civil rights reckonings in 1970s America. As white Vietnam vets struggled with the challenges of adapting to an American social order transformed by the politics of anti-discrimination and cultural representation, they were not simply echoing the well-worn refrains of white reaction. Rather, as Darda shows in this wide-ranging and provocative tour through the post-Vietnam cultural and political scene, they fashioned their own new brand of therapeutically inflected grievance politics, poised to capitalize in a host of ways on America’s emerging postliberal backlash.

Conditions were ripe for returning Vietnam vets to engineer this dramatic change in status. The so-called white ethnic revival announced a defection from the old model of WASP ascendancy, and the assertion of new cultural status on behalf of a cohort of twentieth-century immigrants—Polish, Italian, Greek, and Slovak Americans (or PIGS, in the provocative coinage of white ethnic theorist and eventual neoconservative theologian Michael Novak)—who bore limited culpability for the original sin of Black slavery. This reconfigured model of the white immigrant experience “turned white people into minorities, innocent and self-made,” Darda writes, while the culture-first logic of the white ethnic revival permitted these reborn white Americans “to attribute the material barriers that Black and brown Americans faced in education, health services, housing, law enforcement, and wealth accumulation to culture and choice.”

The emerging new politics of white blamelessness came to a head in the 1978 U.S. Supreme Court decision Regents of University of California v. Bakke. The plaintiff in that case, a Marine vet in Vietnam named Alan Bakke, alleged that he was a victim of reverse racial discrimination after the University of California at Davis twice rejected his medical school application in favor of nonwhite candidates selected under a quota system. The court ruled in his favor, and in place of the putative discriminatory nature of admissions quotas, the Bakke majority endorsed the far more amorphous-to-subjective metric of “diversity” to justify minority outreach efforts in college admissions programs—thereby vastly complicating measurable progress in racial representation while helping to launch a top-down human resources land rush in diversity training and institutional image management.

Other returning Vietnam veterans, meanwhile, were coping with the challenges of reintegrating into an America society that seemed ashamed of the failed Southeast Asian war—and indifferent to hostile to the plight of veterans of the conflict. The mounting sense of anomie in the white veterans’ community became focused on the notion of post-traumatic stress disorder—a new psychological diagnosis that took root after a nurse in a Boston VA hospital treated a veteran who’d taken part in the infamous massacre of some 500 Vietnamese villagers in My Lai. By the time PTSD was formally adopted in the 1980 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the notion of post-Vietnam trauma was already spreading beyond the corps of afflicted veterans and gaining traction as an all-purpose depiction of white male grievance in a contracting economy and a still-confrontational climate of post–civil rights and feminist protest. “The attribution of PTSD to vets and the white men who identified with them, most of whom did not serve and did not suffer from PTSD” worked “as a kind of entitlement,” Darda writes, “a belief that something they deserved had been taken from them, had been taken and must be returned. It encouraged a feeling of entitlement through a sense of discrimination.”

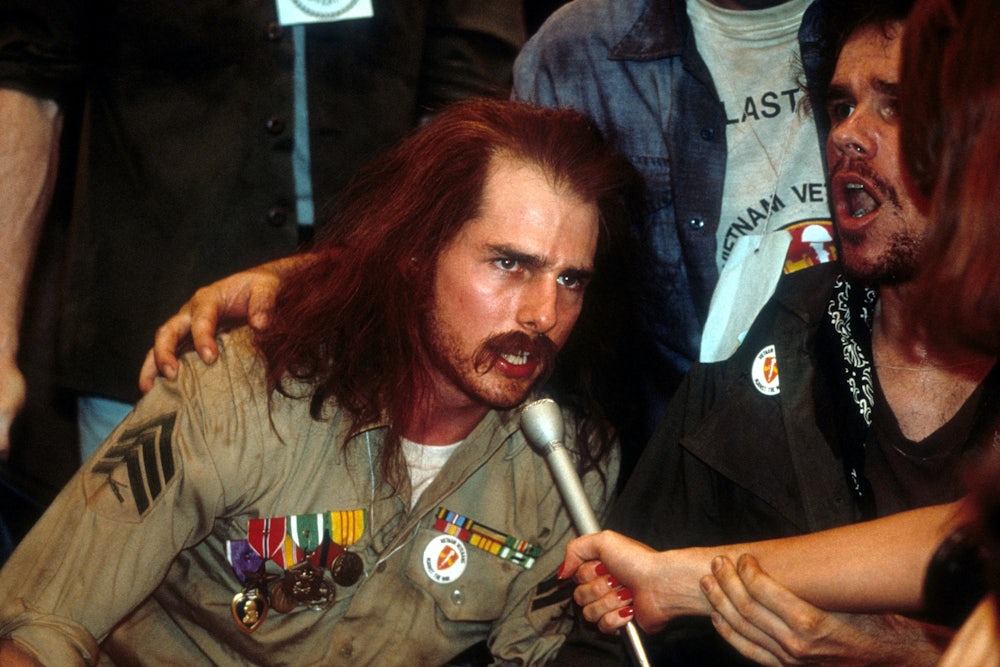

In a telling augur of this shift, Vietnam Veterans Against the War—a militant anti-war group that gained notoriety when several of its members (among them future senator and presidential candidate John Kerry) hurled their service medals over a fence near the White House—began to focus principally on issues of trauma and recovery, sponsoring a series of “rap groups” to describe the harrowing experience of combat in Vietnam and vets’ halting efforts to come to terms with its psychic legacy. White veterans dominated in these sessions, as well, and even when they recounted stories of atrocities that they’d carried out in Vietnam, the psychologists who moderated the VVAW encounter sessions diagnosed them as “survivors” of PTSD, effacing difficult questions of accountability and guilt in “a dehistoricized trauma culture in which all could claim the status of survivor,” Darda writes.

Another potent channel of this emerging dynamic of white blamelessness was the Prisoner of War/Missing in Action movement, which also managed to transmute a cross-racial vets’ issue into a politics of white grievance. As part of the phased withdrawal of troops from Vietnam, the Nixon administration orchestrated a high-profile return of 591 American prisoners of war in the spring of 1973, in an initiative dubbed “Operation Homecoming.” The returning prisoners were acutely unrepresentative of the actual forces serving in Vietnam: They were mostly college-educated officers. None of them had been drafted. They were all men, and 95 percent of them were white; the most famous among them, John McCain (another future senator and presidential candidate), built a political career on the idea that his sacrifice and suffering were emblematic of his generation of veterans. From this lily-white, mediagenic presentation of returning prisoners of war, an activist movement took root, seeking the return of allegedly still-living POWs in Vietnam who were chiefly figments of urban legend—and the broader optics of the American veterans’ movement ensured that these imaginary figures had to be white. “The whiteness of the Operation Homecoming vets, the most visible and distinguished former prisoners of war, made the POW/MIA movement a vehicle for white racial grievance,” Darda writes, “and the POW/MIA flag has been a common sight at white supremacist rallies ever since. When a 1985 Newsweek headline declared ‘We’re Still Prisoners of War,’ some readers, whether conscious of it or not, would have taken that ‘we’ to mean white America.”

Not that anyone needed, by that point, any additional prompting to envision the ideal type of the Vietnam vet as white and aggrieved: American pop culture in the 1980s teemed with fables of white Vietnam veterans fighting for recognition and some measure of vengeance in an America that preferred to ignore or abuse them. Bruce Springsteen’s stadium-rock anthem “Born in the U.S.A.,” the title cut from an album that clocked more than 30 million sales, bemoaned the alienated state of its narrator, a returned Vietnam vet, between a shouted chorus that could well have doubled as a title for a tract in the white ethnic revival genre. Not surprisingly, the song drew accolades from President Ronald Reagan—whose reelection campaign briefly tried to adopt it as a theme—as well as Reagan-allied propagandists such as high-Tory opinion columnist George F. Will. Reagan’s opponent, Walter Mondale, also tried to seize on the song as a rallying cry and even spuriously claimed that the Boss had delivered an official Mondale endorsement.

Springsteen, a fairly apolitical cultural populist at that point in his career, fought off the opportunistic embrace of both Reagan and Mondale. But the campaigns of both men well understood that the failure of Springsteen’s anthem to deliver any intelligible political message was, in fact, the basis of its mass appeal. And as is the case with any document bearing witness to white-inflected grievance, its own identitarian agenda was pretty much hiding in plain sight:

The campaigns understood … that, whatever their candidates would or wouldn’t do for the working class, the white worker and the Vietnam vet meant something else to white men who identified as neither. The insecure white worker of a Springsteen song signified for white men, including most of all middle-class nonvets, that they had their own hard-luck stories, that they had suffered in the wake of civil rights, feminism, and the Vietnam War. The Reagan and Mondale campaigns found in Springsteen, with the subtle mutable racial meaning of his songs, a rare figure of consensus in the emerging culture wars. Who wouldn’t vote for Bruce?

Neither subtlety nor mutability was a going concern for Sylvester Stallone, whose blockbuster 1985 film, Rambo: First Blood Part 2, brought the image of the Vietnam vet back to its jingoistic Cold War roots. Stallone’s title character is dispatched back to Vietnam on a POW rescue mission and delivers his signature catchphrase in reply to the officer briefing him: “Sir, do we get to win this time?” The movie script also goes out of its way to give the character of Rambo a new ethnic identity that hadn’t been referenced in the franchise’s debut film or in the novel that formed the basis of the Rambo series: He’s made half–Native American. As Darda notes, Rambo’s manufactured Indigenous backstory gave a character played by a white actor a way to co-opt a narrative of discrimination: “The white ethnic revival had made white minorities the most American thing of all.… In the 1980s, that meant a white actor starring as a half-Indian soldier—a minoritization that, as simulated rather than embodied, allowed all white men to see themselves reflected in it.”

Much the same simulacrum of authenticity altered the hallowed status of veteran-ness in the film. When one of Rambo’s overseas handlers—a feckless government bureaucrat based in Thailand—turns out to be lying about his military service record, Rambo more or less shrugs it off. In his debriefing session after the mission, he explains that he only wants “what they [the POWs] want, and every other guy who came over here and spilled his guts and gave everything he had wants: for our country to love us as much as we love it.” The moral was plain, Darda argues: “Veteran status has less to do for Rambo with wearing the uniform than with waving the flag.”

In the world of literature, meanwhile, a new cohort of Vietnam authors, all white and male, such as Tim O’Brien, Larry Heinemann, and Robert Olin Butler, gained canonical stature in American letters—Heinemann’s Vietnam vet novel, Paco’s Story (a “liberal answer to the Rambo films,” Darda writes) famously beat out Toni Morrison’s Beloved for the 1987 National Book Award. The same white male–dominated narrative template held for Vietnam memoirs, such as Ron Kovic’s Born on the Fourth of July, which inspired both Springsteen’s anthem and a big-screen adaptation by Oliver Stone.

This flood of literary recreations of the war crowded out memoirs and fictions composed by Vietnamese writers who had been war refugees; when Stone adapted one such memoir, Le Ly Hayslip’s When Heaven and Earth Changed Places, as the 1993 film Heaven and Earth, the film died at the box office, while critics complained that a movie dedicated to the travails of a refugee rather than a familiar anguished white veteran “lacks an emotional center,” reserving their acclaim for Steve, the traumatized white male American vet in the saga, played by Tommy Lee Jones. Jones’s character is “the most effective, most powerful part of the film,” Washington Post critic Hal Hinson proclaimed. For such onlookers, “the Vietnam War felt abstract and unrelatable … without a dislocated white vet through whom they could channel their anger and grief,” Darda observes. “Critics and moviegoers, most of whom bought tickets to Mrs. Doubtfire and The Pelican Brief that weekend instead, didn’t want to see a refugee saga on the big screen unless it starred Steve, the refugee of [white Vietnam vet memoirs] Brothers in Arms, Going Back, The Circle of Hahn, and No Longer Enemies, Not Yet Friends.”

And so the same cultural dispensation carries down through today. Like Bruce Springsteen and Sylvester Stallone, Donald Trump dodged the Vietnam war draft, claiming four deferments based on dubious diagnoses of bone spurs in his feet. But Trump, who also became a national celebrity in the vet-obsessed 1980s, seized the image of the brave defender of defiled veteran honor. In 2016, speaking before D.C.’s traditional POW/MIA Rolling Thunder motorcycle rally, Trump declared that “in many cases, illegal immigrants are taken better care of by this country than our veterans.” No one had to point out that the image of the veteran Trump evoked was white—or that the “illegal immigrants” he had in mind weren’t. Even after he’d maligned the military service of John McCain earlier in the campaign, Trump won the enthusiastic support of the assembled POW/MIA activists—and of the white nation that vicariously identified with them. In the 2018 midterms, Democrats sought to follow his lead, recruiting a slate of nearly 100 mostly white veterans to attract voters from the long-fetishized center right.

In other words, the national consensus rested pretty much just where Bruce Springsteen and John Rambo had left it—and white men could comfortably reclaim their historic role at the center of American power, shrouded in a gauzy mythos of innocence violated and reclaimed. As Joseph Darda makes clear in this eye-opening study, they had won something far more valuable and enduring than a culture war.