John and Revé Walsh’s lives changed on July 27, 1981, when Revé took her six-year-old son, Adam, to the Sears department store in a mall in Hollywood, Florida. Adam had asked to visit the toy department while his mother browsed the lighting and home furnishings section just a few aisles away. As Revé told ABC’s Nightline in 2011, “I said, ‘I’m going right over here to the lamp department,’ and he said, ‘OK, Mommy, I know where that is.’” After Revé bought her lamp, she went to collect her son, but he was nowhere to be found. A frantic search of the store ensued, followed by what some observers called “the largest manhunt in the history of Florida.”

Two weeks later, after an appearance on Good Morning America, Revé and John learned that their son’s severed head had been discovered in an Indian River County canal, a little more than 100 miles north of the scene of his disappearance. Just as the Walshes’ search for their missing son had unfolded on national TV, their expressions of grief beamed to television sets nationwide.

The couple channeled their highly publicized sorrow into a growing national movement focused on child safety, “victims’ rights,” and “law and order.” John Walsh, specifically, emerged as a high-profile advocate for missing and exploited children and for more aggressive policing and punishment. Conveying paternal strength and righteous anger on television and elsewhere, Walsh spoke for Americans who were “sick of the level of violence in this country” and wanted “to do something about it,” as he told a 1995 congressional subcommittee. In his co-authored 1997 book, Tears of Rage: From Grieving Father to Crusader for Justice, Walsh discussed the activism he undertook immediately after his son’s murder. “I was a man possessed,” he wrote. The book also revealed Walsh’s contempt for inept law enforcement officials, bureaucratic red tape, and the “slap on the wrist” supposedly enjoyed by those who “rape little girls and … little boys.”

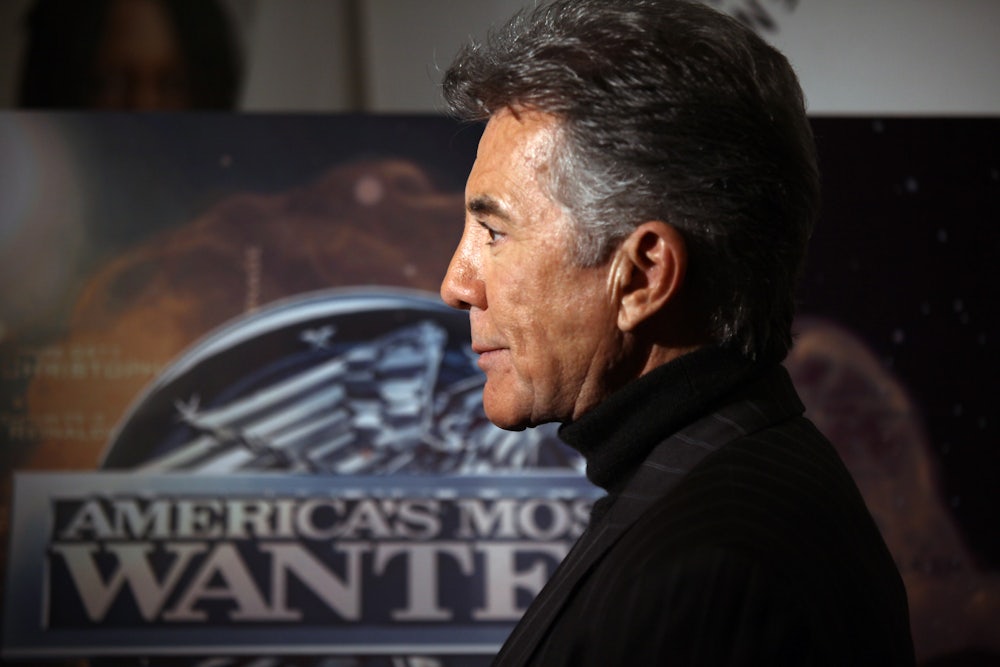

As the host of Fox’s America’s Most Wanted from 1988 through 2011, Walsh would fuel the nation’s crime panic and reinforce his position as the country’s foremost proponent of harsh anti-crime measures. With its grim, gritty tone and dramatic reenactments of violent acts, the show sought to induce fear in the American public, alerting viewers to rare, sensational events and thus distorting their conceptions of crime and danger. Walsh’s status as a bereaved parent and a well-known anti-crime crusader also propelled him into the halls of power (despite his professed distaste for the “backstabbers in the world of politics”), where he bent the ear of every U.S. president from Ronald Reagan through Barack Obama.

Today, 40 years after the murder of Adam Walsh and with a reboot of America’s Most Wanted now airing on Fox, Americans find themselves in the throes of another crime panic. While murders in some major U.S. cities have increased since the pandemic began, New York City is on track to end the year with one of its lowest murder totals on record, and overall crime rates across the country have declined. Crime statistics are also notoriously unreliable and contested, given certain inconsistencies in reporting across agencies and populations. Because many U.S. police agencies have yet to report their data to the FBI this year, “it’s not immediately clear how much, if at all, homicides increased in smaller cities or small towns across the country, or how 2021’s national homicide total compares to 2020,” CNN noted last month.

Despite these issues with reporting, and despite the fact that today’s murder and violent crime rates remain well below rates seen in the 1980s and 1990s, many communities are suffering acutely amid the economic and social dislocations of the ongoing pandemic. The violence of Covid-19 is multifarious: The virus ravages the body, while the economic and political uncertainty left in its wake has led to the violence of eviction, houselessness, anti-Asian harassment and abuse, hyperpolicing, and mass shootings. The communities most deeply affected by this syndemic deserve safety and accountability, as do all communities.

Still, these circumstances do not signal the emergence of a crime wave. And yet the panic is undeniable. Mississippi’s Republican governor, Tate Reeves, recently lamented the “never-ending cycle of violent crime” on display “every night on Jackson’s local news.” (Meanwhile, Reeves mostly seems to be ignoring the coronavirus outbreak that is currently devastating his state.) The political and news media construction of the 2021 “crime wave”—typified by Reeves’s scaremongering and the “tough on crime” politicking that defined New York City’s mayoral race—has convinced “a clear majority of Americans,” according to a recent Yahoo! News/YouGov poll, that “there is more violent crime in the U.S. today than in the 1990s,” the heyday of America’s Most Wanted.

We are still living in the world that John Walsh helped build. He and America’s Most Wanted helped form Americans’ sensationalized, paranoid, and individualized understanding of crime. Neglecting state and private interventions that might address the structural causes of all harm while delivering meaningful justice for all victims and survivors, Americans generally focus on the exceptional victim and the exceptional offense. This prevailing model misrepresents the nature and frequency of harm while offering little in the way of prevention, instead turning back to policing and punishment as the only solution. To break the cycles of sensationalism, violence, and “law and order” policymaking, we must look elsewhere.

John and Revé Walsh lived a comfortable life in South Florida before the summer of 1981. Revé spent her days looking after Adam, their only child, while John worked as a hotel developer. Following Adam’s abduction and murder, the Walshes—particularly John—immersed themselves in anti-crime and victims’ rights advocacy, and John continues to work in that capacity today. John Walsh’s campaign began just as the U.S. criminal legal system pivoted away from rehabilitation and toward a purely retributive model of justice in the 1970s.

The Walshes pressured federal policymakers to pass, and President Reagan to sign, the Missing Children Act of 1982 and the Missing Children’s Assistance Act of 1984. These laws stemmed from the “stranger danger” panic that gripped the nation beginning in the early to mid-1980s. At the time, aggrieved parents, politicians, and talking heads claimed that 50,000 or more children fell victim to stranger abduction in the United States annually. (The actual figure was and remains somewhere around 100.)

John Walsh’s advocacy persisted into the 1990s and the twenty-first century. The infamous 1994 crime bill, signed into law by President Clinton, contained the Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Registration Act, named for an 11-year-old Minnesota boy who was kidnapped, sexually assaulted, and slain in 1989. The Wetterling Act set the foundation for the expansive system of sex offense registration that now ensnares nearly one million Americans. (The 1994 crime bill also authorized “the death penalty for kidnappers who kill children,” a measure that Walsh ardently supported.)

When Clinton amended the crime bill in 1996 by signing Megan’s Law, named for seven-year-old rape and murder victim Megan Kanka, Walsh stood behind the president. Megan’s Law mandated the nationwide adoption of community notification protocols for individuals convicted of certain sex offenses. The 2003 PROTECT Act (“Prosecutorial Remedies and Other Tools to End the Exploitation of Children Today”) included the Code Adam Act, which established protocols for individuals to follow in the event of a missing child in a federal building. (The Code Adam program was first implemented in Walmart stores in 1994.) The PROTECT Act also federalized the similarly minded Amber Alert program.

On July 27, 2006—exactly a quarter-century after Adam Walsh’s abduction—George W. Bush signed the Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act while flanked by John and Revé in the White House Rose Garden. In his remarks upon signing the bill, Bush applauded the Walshes’ “tireless crusade” to “combat child abduction and exploitation across the country,” and he noted the solemn anniversary on which he was signing the bill into law. Among other provisions, the Walsh Act established a de facto national sex offense registry; expanded the number of offenses for which individuals might be forced to register as sex offenders; and developed three tiers into which registrants are categorized, based on the severity of their offense(s).

John Walsh had at least as much of an impact in the cultural sphere. America’s Most Wanted debuted to rave reviews in April 1988, against a backdrop of intense anti-crime sentiment. TV Guide awarded the show its “Best Public Service” prize, and World News Tonight called it “the ’80s answer to the ‘Most Wanted’ poster—criminals and their crimes dramatically brought into homes across America, a blend of news, entertainment, voyeurism, and violence.”

As this news coverage (and the show’s subsequent subtitle, “America Fights Back”) indicated, America’s Most Wanted hoped to spur fed-up, law-abiding Americans into action. While the show appeared to celebrate populist, extrajudicial responses to crime, it actually operated “hand in hand with law enforcement,” in Walsh’s words. As one journalist put it on World News Tonight, “The show has hit upon an unusual partnership” between police, the public, and the media industry. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Walsh remarked, “It’s a way for the public to get involved, to get the violent criminals, without resorting to vigilantism.”

This approach subtly underscored the supposed inadequacies of existing law enforcement systems and practices—all while demanding their fortification. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Americans’ confidence in the U.S. criminal legal system was at historic lows, and fear of crime soared: In a 1989 Gallup poll gauging confidence “in the ability of the police to protect you from violent crime,” half of respondents selected “Not very much [confidence]” or “None at all.” Between 84 and 89 percent of Americans surveyed by Gallup in 1989, 1990, and 1992 sensed “there [was] more crime in the U.S. than there was a year ago.” These figures represented historic highs. In 1992, four years into America’s Most Wanted’s 23-year run on Fox, 83 percent of Americans polled by Gallup said the criminal legal system was “not tough enough,” another historic high.

Filmed on an elaborate set replete with phone operators ostensibly on hand to field viewers’ calls, Walsh’s America’s Most Wanted strove for interactivity, blurring the lines between entertainment and advocacy and convincing Americans that their vigilance could help deter crime and deliver justice. Extended reenactments of heinous violence simultaneously served to demonstrate the gravity of the crime threat and to compel viewers to act as reinforcements for police, investigators, and the courts. America’s Most Wanted also regularly stoked the sorts of moral panics that rocked the suburbs during the late twentieth-century culture wars. In his memorable, authoritative voice, Walsh warned parents and homeowners of the ascetic “straight edge” punk subculture, of murderous vampire cults, and of the “Dinnertime Bandits” who robbed the mansions of the rich and famous at suppertime. These segments either sought the arrest and successful prosecution of an irredeemable, deviant individual or set of individuals or sought to inform viewers of a growing menace or danger. Such splashy material clearly targeted middle-class or affluent (white) citizens anxious about the sanctity and security of their homes and families.

Not unlike its Fox counterpart COPS, then, America’s Most Wanted exaggerated and distorted the threats confronting most Americans and proposed heightened vigilance, policing, and punishment as the appropriate remedies. Some observers recognized as much when America’s Most Wanted first aired in 1988. ABC reporter Jackie Judd gave voice to certain critics who claimed “that [the show] hypes the violence,” while one Legal Times correspondent shed light on the profit motive. “The bottom line for producers and for Fox-TV is money,” he declared, “and in making money they have to sensationalize things.” As Walsh wrote in Tears of Rage, America’s Most Wanted was “an instant controversy. Everyone was asking if this show had finally crossed the line. Had it gone too far? Were the crime reenactments too gruesome? Was this vigilantism run amok?” Nevertheless, fawning coverage of America’s Most Wanted outweighed such criticism, and the show’s focus on “victims’ rights” and on rare, sensational crimes—often committed by strangers—would shape policymaking in the 1990s and into the twenty-first century.

The America’s Most Wanted reboot more or less follows the formula pioneered by its predecessor. As host Elizabeth Vargas told Entertainment Weekly in March, the show seeks “to help catch these fugitives and to bring justice to the victims” by harnessing the power of technology and a vigilant viewing public. In another interview, Vargas claimed that unlike other “true crime” programs, the America’s Most Wanted revival gives “viewers the chance to actually do something.” This remark mirrors the populist language long employed by Walsh.

But when Vargas and Walsh talk about doing “something” about crime and violence at the behest of a frustrated public, it always entails heightened policing and punishment, even though the American project of hyperpolicing and mass incarceration has failed miserably. The U.S. spends nearly $300 billion annually on policing, the courts, incarceration, parole, probation, and related projects—more than the military budget of any nation apart from the U.S. It is not unusual for a major American city to spend 30 to 40 percent of its annual budget on policing. These expenditures have been legitimated through decades of anti-crime fearmongering by elected officials and the media. Yet such outlays have not guaranteed public safety for all, as each nightly news broadcast and America’s Most Wanted episode reminds us.

The prevailing vision of crime in America, promoted by Walsh and others over the years, obscures its structural and class dimensions while elevating exceptional cases. Poverty, homelessness, untreated illness, and social exclusion can foster behaviors deemed “deviant” or “antisocial” and thus lead to interactions with law enforcement and the legal system. The dominant American understanding of crime ignores these conditions, as well as the fact that policing and punishment serve to conceal broad societal failures while disproportionately impacting poor and working-class people of color and offering very little to victims and survivors. Indeed, this vision prioritizes criminalization and caging while rendering unthinkable certain policy responses—namely greater investment in housing, health care, education, and other social services.

Instead of contributing to the cycle of anti-crime sensationalism and tough-on-crime policymaking, those concerned about harm and violence should look to alternative models of justice. Over the past several years, scholars and activists long engaged in transformative and restorative justice work—people such as Ruth Wilson Gilmore and Mariame Kaba and organizations like Critical Resistance—have garnered growing visibility and recognition. They take harm and victimization seriously, while acknowledging that hyperpolicing, warehousing, and exclusion—core features of the carceral regime developed since Adam Walsh’s murder—produce their own violence. To build a safer, more secure society, we must abandon this failed regime and the skewed understandings of crime that helped build it.

Four decades after his son’s murder, the political and cultural ramifications of John Walsh’s efforts are clear. The next 40 years may very well witness legal and cultural transformations as vast and substantial as the changes wrought since Adam Walsh’s murder. The question is whether these coming transformations will reinforce or undercut mass incarceration and criminalization—and whether the use of white victimhood and sensational crime reporting as a cudgel, an excuse for state violence and victimization in the name of “justice,” will remain a central, lamentable feature of the American discourse on crime and punishment.