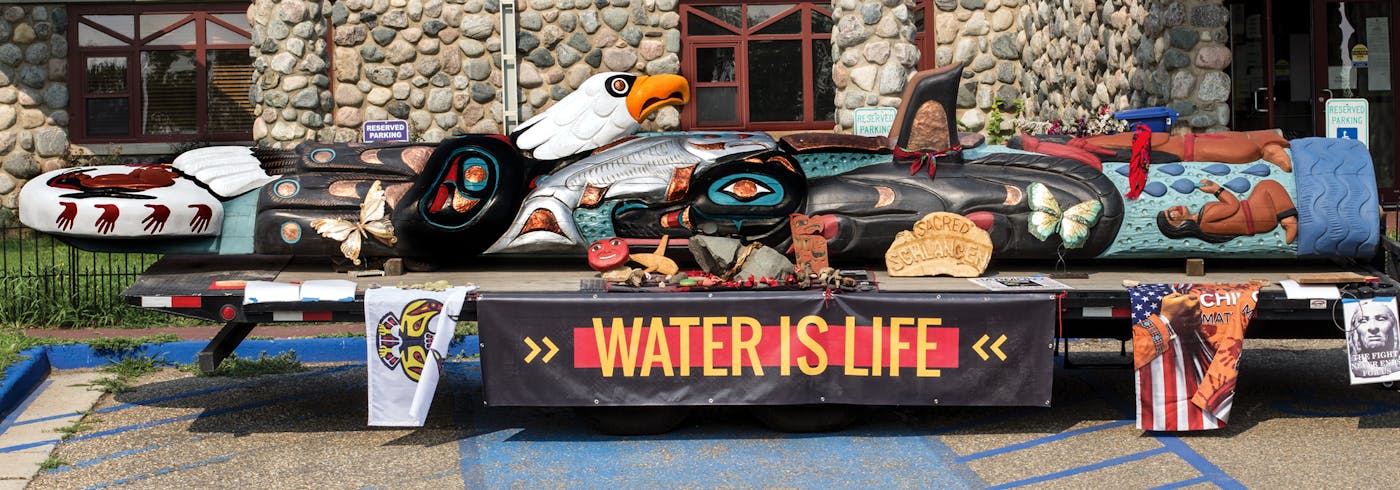

COLONIAL MICHILIMACKINAC, read the sign on the gift shop. The Michigan storefront was tucked under the Mackinac Bridge, which crosses the waters at the meeting point of Lake Huron and Lake Michigan. As the crew poured out of their minivans and sedans and pickups and began to prepare for the day’s event, 18-wheelers rumbled on the highway overhead. In the parking lot, resting on the same flatbed it had been traveling on since it left Lummi Nation in Washington state nearly two weeks before, lay a totem pole. To the north ran the Straits of Mackinac. And beyond that, a pipeline.

It was my eighth day on the Red Road to D.C., a cross-continent trip organized and overseen by a collective of tribal citizens, nonprofit leaders and staffers, artists, and allies, who had joined to shepherd the totem pole eastward as a public call for the protection of Indigenous sacred sites and the sovereign rights of tribal nations. Most of the crew had been with the pole since it left Lummi Nation two weeks ago. The Lummi citizens with the House of Tears Carvers, a group of artists who were responsible for shaping it, were easily the most weathered bunch in the caravan. They’d spent the previous three months visiting tribal nations and sacred sites in the West and Northwest before the official Red Road journey kicked off in mid-July. For the whole caravan, and for our Lummi friends—carver Doug James; his wife, Siam’elwit; and his nephew Phreddie Lane—this was the final stretch, today’s stop the penultimate event before the 25-foot-long, 5,000-pound cedar trunk reached its final destination at the doorstep of Deb Haaland, President Joe Biden’s new secretary of the interior and the first Indigenous person to serve in a presidential Cabinet.

By 10 a.m., a small crowd had gathered to greet the caravan. Folks mingled in the grass next to the gift shop parking lot. The beach next to the bridge, just a stone’s throw from where we stood, was mostly empty. After everyone had smudged and taken a tobacco offering, speakers from the region’s tribal nations stepped forward to address the crowd. In effect, today’s event was a public protest against a planned addition to a portion of Line 5, which splits into a pair of 20-inch pipelines where it runs along the Mackinac lake bed and supplies much of the region with oil and propane. Enbridge, the pipeline’s developer, wanted to add a tunnel underneath the lake.

The addition to Line 5 had been pushed into reality by Enbridge and former Michigan Governor Rick Snyder. Aaron Payment, the chairperson of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, made a point to acknowledge the initial ignorance of the United States and Enbridge about the environmental costs of such development. Line 5 was installed “before we knew better, before America knew better, before we knew about the threat,” Payment said. But now, the threat is realized. The continued construction of natural gas and oil and coal infrastructure is not a viable path to a livable, healthy planet. As Payment pointed out, Line 5’s 68-year-old dual pipelines are already responsible for at least 1.1 million gallons of spilled oil. “It is going to fail. It is going to spill a million gallons of oil into the water. It’s not a matter of if but when.”

The Red Road caravan had journeyed from Lummi Nation to the Snake River dams in Idaho, then continued south, to Bears Ears in Utah and Chaco Canyon in New Mexico. Turning north, it sprinted through Colorado on its way to the Dakotas, stopping by Lakota lands in the Black Hills, Yankton Sioux lands along the Missouri River, and Standing Rock. Finally, the caravan turned east. It made first for northern Minnesota, where activists from the Anishinaabe tribes known as “water protectors” have set up camps protesting the replacement of parts of Line 3, an oil pipeline that runs from Alberta to Wisconsin (hello again, Enbridge). Now the group had arrived in Mackinaw City and the Straits.

For me, traveling on the Red Road after a pandemic spent largely separated from my own tribal community was a revitalizing experience. It also clarified the profundity of the challenge facing Indigenous populations in the United States. Tribal nations have a basic right to consultation—the same right any sovereign nation possesses to be informed of foreign projects that might affect their citizenry. Accordingly, companies and the federal agencies tasked with regulating them must contact tribes and alert them of any plans that might impact the nation’s community. In theory, consultation happens continually. Nearly every day, people working for their tribal governments wake up to emails notifying them about new projects—and thus the tribes, under federal law, have been “consulted.” Tribes’ right to consultation is rarely if ever properly respected. Across Indian Country, tribal nations are constantly forced by governmental negligence to spend time and resources protecting their sovereignty, their citizens, and their sacred sites. They must fight pipelines, mines, dams, regulators, corporations, elected officials, lobbyists, and, in some cases, other tribes, who may be economically welded to these extractive industries.

By the time the caravan had reached this penultimate stop in Michigan, it had become clear to me that to focus on any one fight in Indian Country to the exclusion of the others was to miss the forest for the trees. In a technical sense, the solution to tribal nations’ troubles likely requires Congress to pass legislation that sets a federal standard for the consultation process and moves the United States toward the long-term, far more ambitious goal of establishing free, prior, and informed consent as a baseline policy—in other words, we must enshrine in U.S. law the right of Indigenous nations to be made aware of a given project and be allowed to reject it. But an even deeper shift is needed. If there is any hope of ending the vicious cycle in which tribal nations are perpetually brushed aside in the name of America’s domestic interests, the United States must willingly relinquish the political power it stole from this land’s Indigenous people. Consultation, after all, is only meaningful when the entity consulted is allowed to give an inconvenient answer. The federal government—Congress, the courts, the White House—must steel itself for a day when the tribes can, and do, say, “No.”

I had first heard Doug James tell the story of the totem pole six days before, in the Black Hills. We were standing on Lakota lands managed by NDN Collective, a nonprofit organization based out of Rapid City that had turned the site, nestled between a subdivision and a National Guard training facility, into a safe place for the city’s unhoused population. Boots planted firmly in the dew-stained dirt, James cast his hand out over the massive Washington Red Cedar trunk strapped to the flatbed before him. He and his brother Jewell, who had to pull out of the trip due to health concerns, had labored over the log together in their shop back home. James traced the pole’s carvings: the full moon at the top, holding the prayers for the next seven generations; the eagle; the Chinook salmon; a sea bear on one side and on the opposite side a sea wolf, which represents the orcas that traditionally share the waters around Lummi Nation’s San Juan Islands and have been captured and put on display in aquariums around the world; the copper plate; the feather, borne of a dream Jewell had in which he tried and failed to grasp a feather floating outside his cousin’s car window. “It wasn’t meant for him to take the power,” Doug said.

Doug handed the mic to his wife, Siam’elwit, who described how federal law intrudes upon Native families and communities. It wasn’t an accident, she explained. The law was designed to “divide,” and to induce trauma. Siam’elwit pointed to the top of the pole, to the red hands on the moon that represent the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women. (Indigenous women are murdered at a rate that is 10 times the national average, thanks in part to perpetrators both within and without tribal communities who exploit the indifference of law enforcement.) She turned to the imprisoned ancestors represented at the bottom of the pole, those who had been ensnared by the border and anti-migration systems imposed by the federal government. And she described what needs to be done to stop the cycle. “When somebody wants to come near the sacred places, we want to have a voice in that matter,” Siam’elwit said. “We want to have a right to say ‘No.’ And no means no.... Stealing land: No. Taking the sacred places: No.”

A day later, the Red Road carried us to the Missouri River, the southern boundary line for the Yankton Sioux Reservation. There, on the riverbanks, Doug and Siam’elwit and the Red Road members sat and intently listened to Kip Spotted Eagle, the director of the Tribal Historic Preservation office, or THPO (rhymes with “hippo”) for the Yankton Sioux Tribe. Ideally, THPOs should be one of the central points of contact whenever a government agency has a project in mind for lands that are either currently or traditionally stewarded by a given tribal community. But, as Spotted Eagle explained to the crowd that day, not only is his office underfunded, but consulting with tribes is “always an afterthought.” In the paradigm established by the federal government, tribes are brought into the consultation process only once a developer and the permitting agency have worked out the details of the plan—after “everything has been paid for, everything’s been drawn, everything has been planned.” The approach invariably sets the stage for conflict, Spotted Eagle said, because the tribe is put in the position of trying to reject or change a project that is already in motion. “So that’s adversarial.”

The Yankton Sioux Tribe fought both the Dakota Access and Keystone XL pipelines. It filed suits against the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for granting permits to the Dakota Access operators, and it appealed a vote by the South Dakota Public Utilities Commission to approve Keystone. As Spotted Eagle detailed, these legal actions are costly, adversarial responses, but they are the inevitable outcome of a consultation system devised merely to appease the law’s minimum standards. Corporations and state governments have the attorneys and budgets they need to win a war of attrition in court. The problem is that the construction, extraction, and pollution that happen in the interim, while the court system slowly works through a tribe’s challenge to an already-operational pipeline or dam or mine, are sometimes irreversible.

As just one example of a permanent consequence of the government’s actions, Spotted Eagle described the discovery of the bodies of three relatives of his tribe, estimated to be 1,500 years old, in the riverbank. They had likely been buried at the top of the hill, far from the river, and, according to Spotted Eagle, were believed to be a mother and her two children. But the practices of the Army Corps of Engineers, particularly its management of the water in nearby Lake Andes, had compromised those graves. “Human remains are constantly coming out of the riverbank,” Spotted Eagle said. “And those are our people.” He has repeatedly argued in front of state and federal regulators that the government cannot view its consultation duties as ending at the boundary of the Yankton Sioux reservation. “The entire Missouri River Basin needs to be considered a sacred site,” Spotted Eagle told the crowd. “Our people were here. There’s no way to erase that.”

Four days later, I was waist-deep in the Shell River in northern Minnesota, sitting on a fallen tree that the fish had happily assumed as their own. I swung my feet through the clear waters. Grass some eight feet tall, sprouting from the riverbed, rustled in the slight breeze. Standing nearby in the water, Winona LaDuke, a citizen of the White Earth Nation, held court as a small group of a dozen or so gathered before her on the riverbank. “They’re greedy,” LaDuke said of Enbridge, the Line 3 pipeline developer. She shook her head. “Pumping five billion gallons of fresh groundwater.” LaDuke’s ire concerned a decision made in June by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) to approve Enbridge’s request to increase the amount of groundwater it pumped almost tenfold over the amount to which it had originally agreed in November 2020.

The Line 3 addendum project does not run through reservation lands in Minnesota; rather, it cuts between the reservations of the Red Lake Nation and White Earth Nation. The gap between the two reservations is just 30 miles wide. Thanks to the pipeline’s careful placement, neither tribal nation legally merited consultation by the DNR about the drastic uptick in pumping. We’d passed the yet-to-be-connected pipe segments on our way in. Piled next to the road, steel gleaming, they almost felt like a taunt. Diverting such a massive amount of water during a significant statewide drought could negatively impact the manoomin, or wild rice, that the tribes have stewarded for centuries. Without meaningful consultation, the tribes had to resort to litigation. On behalf of White Earth Nation, attorney and White Earth citizen Frank Bibeau filed a lawsuit in tribal court in early August, naming the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources as a defendant and, in a first in tribal law history, naming manoomin as one of the plaintiffs. The lawsuit builds upon a 2018 act by White Earth Nation and the 1855 Treaty Authority, in which the nation issued a Rights of Manoomin declaration that was designed to grant the rights of legal personhood to that natural relative.

Activists had erected the Shell River camp, one of several along the pipeline’s route, to oppose Line 3. The crowd that had gathered for LaDuke’s speech eventually trickled back from the river to the adjacent campsite, where the horses were resting, and where the Red Road caravan had parked. There, the travelers spoke to the water protectors and allies at the camp. Siam’elwit’s message had broadened since she spoke outside Rapid City. This time, she addressed the Major Crimes Act of 1855, which undercut tribal courts and imposed federal jurisdiction over sovereign lands; and Public Law 280, a federal statute passed in 1953 that was designed to grant state court systems the authority to try criminal and civil cases of non-Native defendants charged with crimes on tribal lands. Extraordinarily, non-Natives cannot be prosecuted in tribal court, she explained. “The violent crimes on reservation continue to be overseen by the U.S. government.”

The pain caused by the disparate tragedies the tribal nations have faced is immeasurable, and their immediate causes unique. But undergirding it all—the exclusionary permit process for infrastructure projects, the relative lack of tribal co-management plans for dams and waterways, the jurisdictional mess that is law enforcement on tribal lands—is a common thread. In every instance, as the United States was crafting its legislative and executive policy around these and so many issues, the federal government could have consulted with tribal nations to understand what they wanted and needed for their citizens’ long-term survival. Instead, the government chose to cover its ears.

It hasn’t always been this way. For the first five decades of America’s existence, treaties were negotiated on a nation-to-nation basis. To be sure, the United States relentlessly broke those treaties, but, from a procedural standpoint at least, the White House weighed and understood its relationship with each of the individual sovereign nations. More important, it recognized that when entering negotiations, tribes maintained the right of consent. The United States did not have the authority to dictate what would happen on their lands. And so, as the federal government shook the hands of tribal leaders and signed the treaties, it began to look for a work-around.

The short version of this history is that, in spite of its initial recognition of tribes’ sovereignty, the government has always dearly wanted Native land, and, as such, its White House, Congress, and Supreme Court have always been willing to bend or outrightly ignore precedent in the name of obtaining it. One of many such examples is the 1832 Supreme Court case Worcester v. Georgia, in which Chief Justice John Marshall offered the double-edged ruling that tribal nations were “distinct, independent political communities,” upholding their sovereign status while also finding them to be “domestic,” dependent nations. This decision officially rang in the ward-of-the-state relationship that subsequently drove the nation’s tribal policy.

Congress facilitated and approved the trust responsibilities the United States assumed, and endorsed the imbalanced political relationship with the tribes that the ruling established. This update neatly coincided with an all-out blitz on Native land by the U.S. military, American citizens, and corporations of all industries. Treaties were signed, violated, rewritten at gunpoint. In the name of expanding the nation’s borders and securing resources, every administration from Jackson to Lincoln forcibly displaced tribal nations, massacred them, and corralled them onto reservations. This was white supremacy and manifest destiny in action. And yet through it all persisted a political relationship. Reservations, though mere slices of the land areas initially agreed to, were still considered sovereign lands under the control of the tribes. So the government sought to undermine that designation as well, with measures such as the Major Crimes Act, which imposed its legal structures on Indian Country.

From the mid-nineteenth century forward, the United States sought to act as a trustee, restricting Native people to their reservations while furnishing them with the bare necessities as an empty gesture toward upholding the treaties that its own Constitution declares the “law of the land.” This approach lasted through the 1940s, at which point the combination of American apathy and treaty violations finally made the condition on many reservations untenable, and created a public relations crisis for the federal government. Tiring of the trust relationship it had held with tribes since the creation of the reservation system, the government began seeking to erase Native nations off the map politically and culturally, and the Termination Era commenced. To achieve the erasure, the Bureau of Indian Affairs implemented measures such as the Urban Relocation Program, which operated on the general principle that if only a handful of Natives remained on their lands, few people were in a position to enforce their tribes’ treaty-enshrined legal and political rights, and Congress and the White House could dissolve the trust relationship and ultimately terminate the tribes’ status as sovereign nations.

The federal government entered the age of tribal self-determination only recently, with the administration of President Richard Nixon. In other words, a mere 50 years have passed since the United States accepted as official policy the idea that tribes and tribal citizens should exist politically. And the government has only really gotten serious about consultation in the last decade. Indeed, to properly understand consultation, you have to understand precisely where the government is in the process of reorienting its relationship with tribal nations, said Kristen Carpenter, a professor of law at the University of Colorado Law School. (In 2017, the U.N.’s Human Rights Council appointed Carpenter the North American member of the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.) Even in the 1990s, the paradigm was very much still a unilateral one, in which the federal government had final responsibility over tribes. In the Clinton administration’s discussions of consultation via administrative regulation, the actions deemed consultative were more “like an invitation to the table,” as Carpenter put it—they did not constitute “a meaningful government-to-government negotiation over an issue.”

In November 2000, Bill Clinton signed Executive Order 13175, which sought to “establish regular and meaningful consultation and collaboration with tribal officials.” The mandate, which enshrined the consultation process in law, signaled a major shift—and was also the absolute least the Clinton administration could do after its Office of Management and Budget had spent the previous eight years routinely lowballing the Bureau of Indian Affairs while Congress underfunded crucial, treaty-mandated social and health services. In addition to Clinton’s executive order, there have been piecemeal consultation policies passed into statutory law—such as the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, known as NAGPRA, and Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act—that, while still in need of fine-tuning, have been designed to avoid the adversarial relationship Spotted Eagle warned of. Tribal communities now have a viable path through NAGPRA to repatriate the remains of their ancestors stolen by museums and looters, while Section 106 demands that a federal agency consult with tribes whenever it identifies a project that has the potential to disturb or interact with historic properties. But the laws employ vague definitions of consultation, and offer limited interpretations of the conditions that necessitate it. Consequently, the question of whether corporations and federal agencies are able to skirt NAGPRA, Section 106, or the National Environmental Policy Act regularly hinges on which judge or court is hearing a case.

Of course, a history of tribal consultation is not complete without consideration of how the federal government decides which lands merit it. Presently, save for the few instances defined by the legislation mentioned above, consultation is almost exclusively confined to projects happening within present-day reservation boundaries, despite the fact that many of these boundaries have been repeatedly violated and constricted by the U.S. government. But the reservation is only one part of the homeland, as it’s called by Matthew L.M. Fletcher, a citizen of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians and the director of the Indigenous Law & Policy Center at Michigan State University. “The tribe’s interest is everything that touches the potential of the homeland,” Fletcher told me. “A lot of people say, ‘Well, that’s way too big.’ But keep in mind, the tribes gave up way more than they received.”

The trouble is that, unlike the United States, which has rewritten its laws repeatedly to allow it to interfere in foreign affairs in the name of purportedly improving or defending domestic conditions, tribes have very little by way of legal recourse to affect off-reservation activities that might negatively impact the homeland—such as, say, an oil spill just 50 miles away in a region’s main source of fresh water. “The courts will never see that,” Fletcher said. “They’ll look at the lines drawn on reservation borders. They’ll look at lines drawn on the lakes and say, ‘Here, your interests end here,’ which is ridiculous, because the interests—the world—doesn’t take that into consideration. Nature doesn’t take these arbitrary lines into consideration.”

Here are two truths about our current moment: The Biden administration has already established itself as head-and-shoulders above any modern White House on the matter of consultation. And yet the Biden administration’s standards are still vastly subpar—even when viewed in the bloody context of all U.S. history.

The example of Enbridge perfectly illustrates the emptiness of the consultation process in its current incarnation. Bryan Newland, a former senior policy adviser for the Obama administration’s Office of the Interior and a former president of the Bay Mills Indian Community, worked to oppose an addendum to Line 5. In 2019, he excoriated the Line 5 consultation process on National Public Radio. Enbridge didn’t “have an interest in actually working with us and treating us like sovereign governments with legal authority and legally protected rights,” Newland said. The company “would prefer to say ‘We’ve been talking to the Indians, we’re trying to make the Indians happy.’ And we’re a prop.”

Now, Newland is back at the Interior, working within the Biden administration as the assistant secretary for Indian affairs. I spoke to him, just a few days before he was sworn in, about the way he and his office were thinking about consultation as a departmentwide standard. “At one point in this country, the federal government had a paternalistic role with Indian people, where it effectively said, ‘We are going to manage your lives, and we are going to decide what’s in your best interest,’” Newland recalled. “The United States, thankfully, has abandoned that as the legal relationship.”

To speak of “abandoning” that paternalistic relationship may suggest, perhaps, that it’s in the distant past. But it was the Obama administration that sought to ramp up domestic gas and oil production and secured permits for both the Dakota Access and Keystone XL pipelines, despite the information both the Interior and the Army Corps of Engineers received from the affected tribes. What’s more, the federal government’s failures to adequately consult with tribes extend far beyond those two hot-button pipelines. After interviewing officials from dozens of tribes and 21 federal agencies throughout 2016—right on the heels of the Obama years—the Government Accountability Office published a report in 2019 that found that 67 percent of tribal officials believed agencies reached out too late about projects. Additionally, tribes felt that “agencies often do not adequately consider the tribal input they collect during tribal consultation when making decisions about proposed infrastructure projects.

Now, in the wake of the Trump administration—during which the president suspended the annual White House tribal leaders summit, used the Interior as a one-stop shop for all of the mining and drilling industries’ needs, and, without so much as a phone call, constructed a partial border wall that cut through Indigenous lands—tribes have a reignited interest in improving consultation standards. Likely the best way of immediately doing so would be to institute a governmentwide definition of what the consultation process should entail. This past May, Democrat Raúl Grijalva of Arizona, the chair of the House Committee on Natural Resources and one of Congress’s staunchest defenders of Indigenous sovereignty, introduced a bill designed to do just that. If passed, the RESPECT Act, the most comprehensive legislative treatment of consultation to date, would set broad standards across the board for all agencies to follow. The act would stipulate, among other things, that a tribal impact statement be written up for any future department projects that might interfere with tribal interests. “It’s really an impressive innovation,” commented Fletcher of the Indigenous Law & Policy Center. “A lot of bureaucracy, but ... a really good start.”

That’s the best way to think of the RESPECT Act: as a really good start. Because ultimately, should the bill pass, there will come a day when another president, unconcerned with the duty to uphold a nation-to-nation relationship with tribes, will push the attorneys at the Department of Justice to devise a work-around to the law. When governed by a concept as malleable as consultation has proved to be, even a federal statutory standard can be ducked. Perhaps the only way of avoiding such an outcome would be to enshrine in law the far more ambitious, even revolutionary, standard of free, prior, and informed consent, or FPIC. A consent-based standard would allow tribes to decide what is in their best interest and give them genuine veto power. As the history of Indigenous rights in the United States shows, consent is an old idea that has been ignored. It was repopularized most recently through the United Nations’ 2007 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, or UNDRIP. Since UNDRIP’s call for the introduction of FPIC, however, not much progress on it has been made politically. A consent measure was briefly floated by legislators in Washington state, and was even thought to be on its way into law, but at the last minute Governor Jay Inslee vetoed the measure, sparking an uproar from Washington’s tribal nations.

This past March, during a series of general consultation calls held by Bryan Newland and the Department of the Interior, tribal leaders voiced their resounding support for a consent-based model. “Free, prior, and informed consent should be the goalpost,” Ben Barnes, the chief of the Shawnee Tribe, told the Interior officials. “Any other benchmark is going to fall short of the expectation of tribal nations.” Brian Vallo, the governor of the Pueblo of Acoma, and Ute Mountain chairman Manuel Heart also voiced support for FPIC. Michael Chavarria, the governor of the Pueblo of Santa Clara, said he felt FPIC should be a “guiding light” for the United States and “a prerequisite for any activity that affects our ancestral lands, territories, our natural cultural resources.” Two days later, in a call with tribal leaders in the Pacific Northwest, Lawrence Solomon, the chairman of Lummi Nation, asked the Interior to “improve consultation by requiring our consent on federal actions that affect us.”

In the coming years, the desire for a consent-based model seems destined to grow among Indian Country’s leaders and lawyers, particularly if the Biden administration improves the current consultation process. But any moves by the administration to enact FPIC through either executive edict or legislation could land the president’s departments in a thorny situation. There are clear reasons why consent has not been publicly advanced by the administration, namely that yielding a final say to tribal nations on projects affecting their homeland would inevitably lead to the cancellation or preemptive blocking of infrastructure-related construction projects. Both industry and labor unions whose members would benefit from industry contracts have opposed it on these grounds. In fact, as the Democratic National Committee’s 2020 platform was being written, labor officials quietly opposed the inclusion of a broad call for a consent mandate.

For these reasons and others, Fletcher of the Indigenous Law & Policy Center strongly doubts that FPIC will ever become official federal policy, and he was quick to separate a legislative consultation standard from the consent model central to FPIC. “The RESPECT Act is not even close to FPIC,” he pointed out. “FPIC is a veto power for the tribes to say, ‘Look, we have an interest in this project, we adamantly refuse to consent to it, the project has to end.’ That’s FPIC. FPIC will never happen. Not in any country, not in any state, it just will never happen.” Newland offered a more diplomatic forecast, citing the Interior’s desire to work in the “best interest” of tribes. “Even in the absence of statutory mandate,” he said, “we’re always trying to build consensus for the actions we take across the board, especially in Indian Country.”

On July 29, not long before Deb Haaland was to take the stage for a ceremony at the National Mall honoring the delivery of the totem pole, Doug James and Siam’elwit inspected it where it rested before the podium. Nathan Phillips, an Omaha citizen, walked among the swelling crowd with his dog, smudging those in need of cleansing. I stood under a tent, chatting with Manuel Heart and Navajo Nation Council delegate Davis Filfred. I asked Filfred a simple question: What should consultation look like? “There should be a formal letter,” he told me. “There should be an invite, where there’s a sit-down with all the stakeholders ... where dialogue is open and everything is transparent. There’s not just one call; there’s numerous trips.” Any resolution, he went on, should be signed by the leader of the tribe—in the case of the Navajo Nation, by the nation’s president. “That’s a government-to-government relationship, where a clear consultation is made. Not just a phone call.”

An hour later, Haaland took the stage, smiling broadly. As she surveyed the crowd of several hundred people, mostly Natives, gathered before her, I couldn’t help but feel moved. Here stood the single most important American political figure in Indian Country besides the president, and she had been born to the Pueblo of Laguna. Overhead, blue skies teased us as storm clouds inched their way across the capital city. “Today, and every day, we break barriers to those institutions and systems that were designed to keep us out,” Haaland said. “We’re coming together in a new era—an era of truth, of healing, of growth.” Moments later, she was whisked offstage. More speakers followed, the storm clouds rolled in. The totem pole, after a month outside the Department of the Interior, was moved to its permanent home at the National Conservation Training Center, in Shepherdstown, West Virginia. Like that, the Red Road had come to an end. But the questions it raised remained.

How novel will this administration’s approach be to Indigenous rights? While one of Biden’s first moves was to cancel the permits for the Keystone XL pipeline, the Interior and the White House alike have stood silently by as the Line 3, Line 5, and Dakota Access pipelines all continue to transport oil across Indian Country. Conversely, it is undeniable that the injection of Native leaders such as Haaland and Newland, as well as Chuck Sams III at the National Parks Service and Heather Dawn Thompson at the Department of Agriculture, will force those federal agencies to better respect the legal and political rights of tribal nations.

The question is twofold: How far can these leaders advance the cause of Indigenous sovereignty, and how lasting can their changes be in the event of a Republican presidential victory in 2024? Even accounting for the presence of powerful Native officials within this administration’s top ranks, it seems highly unlikely that President Joe Biden’s White House will enact an executive consent standard such as FPIC this term. And with Congress as logjammed as it is, merely getting the RESPECT Act through the Senate feels like a formidable task.

In other words, even as it becomes possible to imagine a future in which the United States adopts a model of consent, it’s all too easy to imagine conditions changing for the worse at some future point. A consultation law might be passed and even adopted by most federal agencies, only to be unwound in 20 or 30 or 100 years, when the government decides again that it no longer wants to maintain a political relationship with tribal nations. To conceive of Indigenous history in the United States as an arc inevitably pointed toward justice is to ignore the lessons of the past. “I think about it a lot,” admitted Kristen Carpenter, the U.N. expert on Indigenous rights. “You do, just as a student of history, have to acknowledge that the pendulum can swing back and forth.”

Still, Carpenter—like Doug James and Siam’elwit, Manuel Heart, Davis Filfred, Aaron Payment, Matthew Fletcher, Bryan Newland, and, of course, Deb Haaland—remains hopeful about the future of Indian Country. We have to be hopeful, both for our own sanity and for the sake of the nations and communities our ancestors fought so dearly to protect. Perhaps consent will come one day; perhaps we’ll make do with the RESPECT Act. Ultimately, the decision is out of the hands of the tribes. It is a reckoning that the government will have to make on its own, both ideologically and when the gavel strikes the podium and the roll is called. Only then might the United States meet Haaland’s lofty goal of respecting Indigenous sovereignty.