A man emerges from a building onto a busy city street. He turns and walks down the sidewalk, making for a subway station. He descends into the subway, pays his fare, and boards a train. How many people observed him as he went? He passed hundreds if not thousands of pedestrians and drivers on his way from the building to the train—how many of them marked his progress? Did the man at the phone booth watch him? What about the taxi driver idling at the curb? What about the hotel porter, the subway booth attendant, the man reading a book on the platform? Perhaps the man has no reason to believe that anyone is watching, but how can he know?

The condition of being watched, observed, overheard, eavesdropped upon, monitored, followed, pursued, hunted—this is the essential condition of the novels of John le Carré. It is not only the primary subject of his more than 20 works of fiction; it is also the foundational fact of his writerly worldview, the single most important structural component of his narratives. When you move, when you speak, when you write, there is always someone watching.

Le Carré, who died last year at the age of 89, has been celebrated for decades as a writer of what we might call elevated genre fiction—“spy novels.” Given that he emerged out of the Cold War and set most of his novels in that period, it was only natural that after his death he would be praised as a kind of period writer: The New York Times, in its obituary, noted that his “nuanced, intricately plotted Cold War thrillers elevated the spy novel to high art,” while The Guardian said he “raised the spy novel to a new level of seriousness and respect.” When Viking announced earlier this year that it planned to publish a posthumous le Carré novel called Silverview, one press release referred to the author as a “master of spy literature.”

Indeed le Carré did write spy novels, in the sense that his characters are intelligence agents who work for the British secret service, but he also wrote novels about the more fundamental act of spying—the act of training one’s attention on the behavior of another, of learning about another person by watching them with intent and with attention. It was the spiritual ambivalence of this act, more than the political discipline of espionage, that went on to become his most enduring theme. Even 60 years after he began writing, and 30 years after the end of the Cold War, we are still living in a world that is stained and distorted by the ubiquity of observation, the inescapable reach of eyes and ears. No less than the spies in le Carré’s works, we live in a world in which everyone is both watcher and watched, a world surveilled to no end.

Le Carré was born David Cornwell in 1931. His father was a gadabout con man and associate of the Kray crime family and was later arrested for insurance fraud; his mother he knew hardly at all. He suffered at St. Andrew’s boarding school for four years, studied languages at a university in Bern, Switzerland, for two, and thereafter found his way to that most virile breeding ground of British spies, Oxford University. In those days, every don at Oxford was a scout for some intelligence agency or another, unless of course he was a target of those agencies, and in no time at all, the young Cornwell found himself spying on left-wing student groups at the behest of MI5. After a brief stint teaching at Eton, he transferred to MI6, the secret service’s foreign counterpart, and spent several years running agents throughout Eastern Europe. His career came to an unceremonious end when his agent networks and those of almost all his colleagues were blown by the notorious double agent Kim Philby, who defected to the Soviet Union in 1963. His intelligence career having evaporated, he took up writing, and wrote about what he knew—as long as he didn’t use real names, including his own, his minders at the service couldn’t do anything to stop him. He was later assisted in this effort by his wife and collaborator, Valerie Eustace, a book editor who helped shape many of his major works.

Much has been made of le Carré’s own history as a spy—both Adam Sisman’s John le Carré: The Biography and le Carré’s memoirs The Pigeon Tunnel recount his MI6 exploits in detail—but the truth is you don’t need to know much about the man himself to understand the import or the beauty of his fiction. The story of David Cornwell seems to share a kind of structural rhythm with the biographical career sketches that le Carré was fond of inserting into his novels, but the books themselves feel less like dressed-up autobiographies than like social novels that take place within a world drawn from memory. That is to say, le Carré’s career provided him less with a direct source of inspiration than with a background against which he could draw his sharp little characters—not the text of the play itself, that is, but a set of props that could be repurposed for any number of different stories. In a very meaningful sense, his novels occupy a social tradition that descends from Dickens and George Gissing, albeit set within a very constrained sphere of English society.

He first achieved international renown with The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, a moral fable about a grizzled spy who pretends to defect to East Germany in order to avenge the death of his fellow secret agent. From a structural standpoint, the novel is perfect: It begins and ends with a hail of gunfire at the German border and, at every moment between, achieves an ideal tone of desperate tension. The grizzled protagonist, Alec Leamas, is a stark and unforgettable figure, drawn in a few strokes yet impossible not to recognize: The work of espionage has alienated him, emptied him of personality, and it’s this emptiness that makes him the perfect candidate to go behind the German lines.

If the character of Leamas established le Carré as a writer of genre fiction on par with Ian Fleming, it was the character of George Smiley that allowed him to achieve a kind of quasi-literary apotheosis. Intended as a rejoinder to the suave figure of James Bond, Smiley is podgy and perpetually cuckolded, an incapable conversationalist and inveterate mumbler, whose main distinguishing characteristic is his habit of wiping his glasses on “the fat end of his tie.” He appears in at least nine of le Carré’s novels but sees his star turn in a trilogy that revolves around his quest to outmaneuver a Soviet intelligence officer named Karla. The silent war between the dry, patriotic Smiley and the diffident, conniving Karla is one of the great political stories of the Cold War. In theory, of course, the two figures are fighting for different ends, but in reality they both need each other to exist—as one character has it, Smiley and Karla are “twin cities … two halves of the same apple.”

Smiley’s morose attitude provides Le Carré with ample fodder for comic relief during the trilogy’s numberless scenes of muted, bureaucratic repartee, and his constant marital struggles with the unfaithful Ann imbue his professional travails with a fitting air of dry desperation, but there is a deeper point here, too. Smiley succeeds as a spy despite being uncharismatic and clumsy because spies don’t need to beat people up or detonate exploding pens in order to do their work. Spies watch, and record, and remember, all with unfailing attention. If they present as unremarkable old men while doing so, then so much the better—“The byways of espionage are not populated with the brash and colorful adventurers of fiction,” le Carré writes in A Murder of Quality. “A man who, like Smiley, has lived and worked for years among his country’s enemies learns only one prayer: that he may never, never be noticed.”

It is telling, though, that le Carré’s undisputed masterpiece is the one major Cold War novel in which Smiley does not appear. A Perfect Spy is the tale of Magnus Pym, the titular secret agent par excellence who vanishes from Prague one day in an apparent act of defection from the British flag. The book contains vast, gorgeous sections of semi-autobiographical material about Magnus’s father, Rick, who like le Carré’s own father was a roving fraudster and con man who never seemed to show his true face, and indeed it is less about the progress of an intelligence investigation than about the spiritual formation of the people who conduct such intelligence missions. Magnus was raised by an inveterate deceiver, and he grew up to become a deceiver of a different kind—not only a deceiver of his enemies, either, but maybe a double agent who has deceived his allies too. Do these acts of deception represent a redemption of his father’s sins or a surrender to them?

The figure common to all these novels, of course, is the double agent, the man of divided loyalty and multiple identities. The protagonist of The Spy Who Came in From the Cold is a British spy who pretends to be an East German spy so that he can frame an East German spy for being a British spy; the plot of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy revolves around a suspected mole within the Circus, a British spy who is feeding state secrets to the Soviets even as he purports to bring the Brits new intelligence from a supposed Soviet double agent who wants to work for the Brits; the plot of A Perfect Spy revolves around the question of whether Pym is a double agent or just a casualty of the cognitive dissonance associated with spy work.

The result is that the reader begins to wonder whether there are any “single” agents, whether any members of either the British or the Soviet intelligence services can be said to work on behalf of their country and only their country. The effect is to scramble the typical narrative logic of motivation. The question of what any given character wants, which in an ordinary novel would be fundamental to the forward motion of the plot, almost seems to dissolve, since no one could ever know the answer even in the most basic sense.

Any inquiry into personal loyalty becomes an inquiry into informational provenance: Is a given piece of intelligence “gold dust”—that is to say valuable—or is it “chicken feed,” disinformation provided by the enemy? In order to figure that out, the agents of the Circus need to evaluate the loyalties of the agents and agent-runners who have provided the intelligence, but their evaluation of their loyalties, too, is derived from intelligence of whose validity they can never be certain. This is true on the other side too, of course: The Soviet interrogation rooms may be more brutal than the British ones, but the epistemological dilemma of intelligence work plagues Moscow Center just the same way it plagues the Circus, and even when the Soviets penetrate the upper ranks of the British secret service, they never seem to profit by it.

The message here is familiar, and not unique to le Carré: Gaze too long into the abyss, and the abyss also gazes into you. Le Carré’s characters believe in the moral superiority of Western society, and he believed in it, too, but the Circus always seems to be abandoning that moral high ground in its quest to counter Soviet influence. There is a kind of malaise that overtakes both the individual agents and the bureaucratic apparatus as whole. If there is no such thing as pure motivation, there can be no such thing as pure intelligence, and the task of gathering and distributing intelligence is at best an exercise in futility and at worst an act of flagrant self-delusion. Even during Smiley’s final victory over Karla, he has to work hard to convince himself the work can be justified: “[F]or a moment, he weighed the method against the prize, and the distant figure of Karla seemed actually to admonish him.” Whether Karla is admonishing him for being too ruthless or for not being ruthless enough is left for the reader to decide.

Given how much space le Carré’s novels devote to the tangled intricacies of the British-American-Soviet relationship, it would have been reasonable to assume that he would become rudderless in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse. Indeed there is a definite thematic shift in his work around this period, one that revives the globe-trotting tendency of the Hong Kong–set The Honourable Schoolboy and takes the reader to a very impressive suite of settings—Panama, Turkey, Congo, Switzerland, Kenya, the Bahamas, and more.

The expanding frame reflects le Carré’s renewed concerns about the global excesses of postimperial Britain, not to mention the crimes pursuant to the United Kingdom’s participation in the U.S.-led global “war on terror.” If the Circus was well intentioned but self-defeating during the twentieth century, then in the twenty-first century its actions are often outright criminal. At times le Carré’s depictions of post-9/11 intelligence work almost take on the quality of polemic: In Absolute Friends, he castigates America’s self-professed determination to “hunt down its enemies at any time in any place,” whereas in A Most Wanted Man he shows how a trio of national intelligence services conspire to destroy the life of a traumatized Chechen refugee named Issa. If the Cold War novels satirize the tendency to see Bolshevism in every scrap of red, these novels satirize the Western hysteria over Muslim extremism: In a humorous moment, a group of German spies mistakes a Scottish banker lost in Hamburg for a “trained operator” employing countersurveillance techniques in service of Islamist terrorism.

Here, again, there is something else going on. If the shift in le Carré’s later work reflects his awareness of a shift in global politics, it also reflects his sense of the growth of the international observation apparatus we know as “the surveillance state.” Except for a few vague and underinformed references to hacking, le Carré almost never mentions the kind of high-tech gadgetry we are accustomed to associating with alphabet agencies like the CIA and the National Security Agency. Nevertheless there is still the pervasive sense of an eye that can track you down no matter where you flee or how far afield you roam. The mechanisms of intelligence collection and distribution are still analog, even archaic—a few watchers deployed on the street, a subminiature microphone hidden in a household object—but the scope of the information collection process has become so wide as to seem boundless. It’s no longer possible to differentiate “the secret world” or, as Smiley sometimes calls it, “the closed society,” from the ordinary world.

If the Smiley novels are centered around the Circus’s senior ranks on the “fifth floor,” the post-Wall novels focus on the amateurs whom the Circus draws into its fold. There is Barley Blair, the alcoholic bookseller in The Russia House who sojourns to post-Soviet Russia to cultivate a source in the government physics department; there is Harry Pendel, the titular protagonist of The Tailor of Panama, who starts working for the Circus in order to pay off his business debts; and the university professor Perry Makepeace, who finds himself forced to liaise between a would-be defector and the British secret service in Our Kind of Traitor. Intelligence encircles the world, exerts a corrupting influence not only on the sworn members of its bureaucratic ranks but also on every source, every informant, every night watchman, every body double, every driver, every human sacrifice with which these members must do business in the course of accomplishing their uncertain ends. The encyclopedic novels from this post–Cold War period sometimes feel less like Fleming than like DeLillo or Pynchon: Everyone is somebody’s agent, they seem to be saying; everyone is the instrument of a power they have no ability to counter or even recognize.

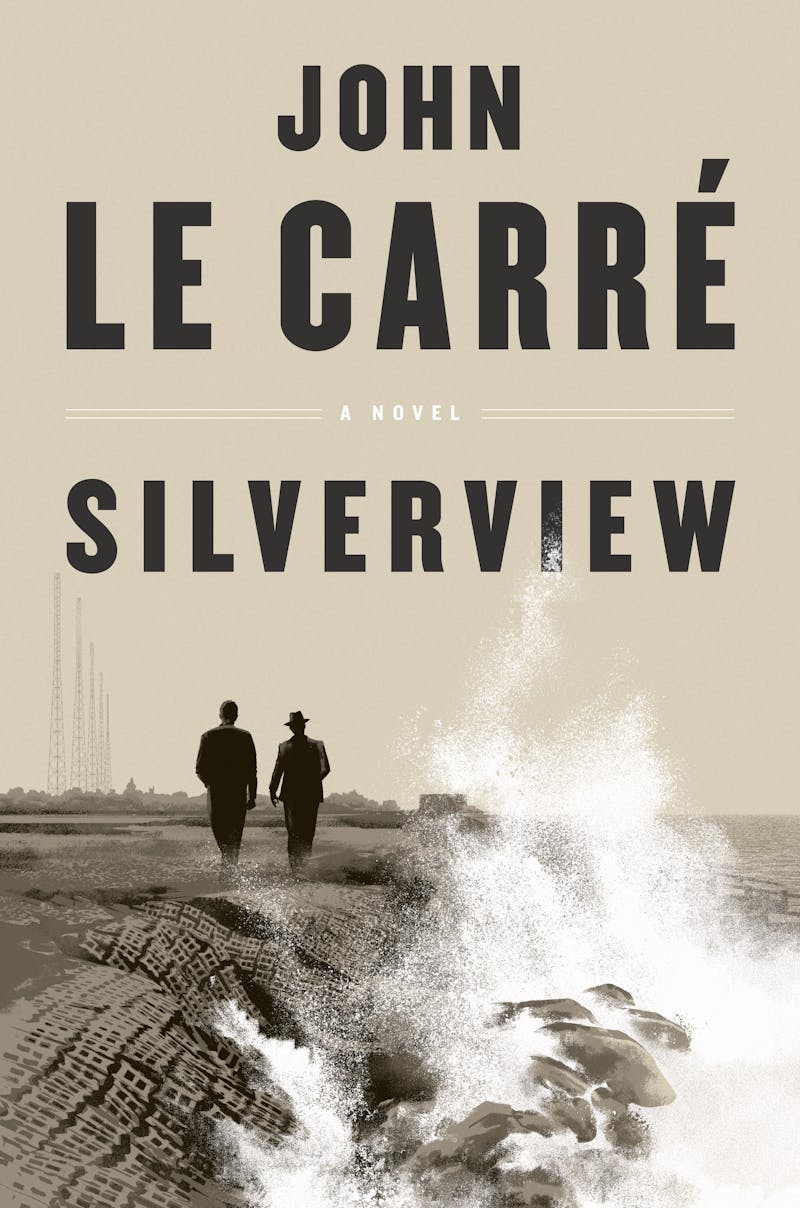

In the afterword to Silverview, the posthumous le Carré novel that Viking will publish this October, the author’s son tells the story of how he dug up the manuscript after his father’s death last fall, having promised his dad he’d publish any unfinished books left behind. Le Carré had started work on the book around 2013, he recalls, and at the time of his death the novel was “written, but never signed off … was it, then, bad?” He fished it out of a drawer, and his “bewilderment deepened … it was fearsomely good.”

Silverview is slim the way posthumous works tend to be. At a mere 200 pages, it is far from ambitious, less a late-career magnum opus than a well-aimed parting shot. The book begins with the story of Julian Lawndsley, a City financier who takes an early retirement and moves to a seaside town in East Anglia to start a bookstore. Lawndsley meets an eccentric quasi-foreign man named Edward Avon, and soon the two men start collaborating on a downstairs addition to the bookstore, except there’s something strange about Edward: He seems to know everything about Julian’s background even before he meets him, he uses the bookstore computer more than seems appropriate, and he sends Julian up to London to deliver a “much-sealed envelope” to a mysterious lady with a “placeless” accent.

In le Carré’s more verbose period, this story alone might have provided fodder for a novel of considerable length, but here he squeezes in a second story as well, tracing an alternate course to the same destination. This alternate plot follows Stewart Proctor, a kind of internal auditor or “bloodhound” for the Circus who investigates and cleans up intelligence leaks. Much like the reader of a John le Carré novel, Proctor’s business is to figure out who knows what and how they know it. This sniffing work, rather than Julian’s encounter with Edward, turns out to be the spiritual heart of the novel. As Proctor follows the trail of a leak within his own service, he roams through the physical ruins of the British nuclear empire: “miles of empty airstrip,” “a windowless railway carriage forty feet long,” “storage chambers and [a] maze of tunnels down there in the netherworld.”

Silverview comprises a kind of trilogy with the last two novels that were published while le Carré was still alive. All three books follow internal affairs investigations within the Circus, concentrating on the internal machinations of the intelligence bureaucracy rather than the external adventures of the spies in its employ. The short novel A Legacy of Spies revisits the double-agent operation from The Spy Who Came In From The Cold, casting the plot that made le Carré famous in a considerably less charitable light; Agent Running in the Field, meanwhile, follows a pair of British spies who both betray their country for separate but noble goals.

The tone of these novels is somewhere between rueful and accusatory: If George Smiley praised intelligence work because it gave him “the opportunity to pay” his country back, the characters in le Carré’s final novels are downright hostile toward Britain, excoriating its “minority Tory cabinet of tenth-raters” and its “pig-ignorant foreign secretary,” now the prime minister. It’s only a matter of time before the intelligence “deep state” begins to follow the dictates of the idiots running the daylight government, and what’s a spy with integrity supposed to do then? Thus the act of unsanctioned disclosure, which in the Smiley novels figures as the ultimate betrayal, figures in these novels as a natural function of conscience for those imprisoned in the secret world. The final trilogy wheels back around on the figure of the double agent, reframing the act of defection not as a tragic betrayal of political ideals but as an essential structural feature of a duplicitous society.

Having shown how espionage encircles the globe, le Carré attempts in Silverview to take the premise to its next logical conclusion—that is, he attempts to prove that surveillance is by nature cannibalistic. If we watch everything, observe everything, it follows that we ourselves are observed, not only by our enemies, but by ourselves as well. Furthermore, our knowledge that we are being watched cannot but influence how we do our own watching. The clearest proof that we live in such a world is the real-life city of London itself: The city contains more than half a million security cameras, owned by a hodgepodge of private firms and public agencies, so that according to one estimate the average Londoner is captured on video 300 times per day. Le Carré wants to say that this act of societal self-surveillance is less navel-gazing than self-immolation, an act that destroys both the watchers and the watched. And is it just an accident of history that one of the most surveilled places on the planet is also one of the dreariest?

The information-gathering process in le Carré is always physical, conducted by “street watchers” or “lamplighters,” but the ubiquitous presence of these physical spooks, too, can serve as a kind of metaphor for the universal reach of digital surveillance. It doesn’t much matter whether we are observed by a suspicious man in a minivan or by a phone that pings our location several times per hour. The effect is the same regardless: The impossibility of solitude entails the corrosion of personality, the transformation of subjects from opaque actors into transparent vessels through which the act of observation passes as light through a prism.

The title of Silverview refers to a manorial house in East Anglia that belongs to Edward’s wife, but the name could also serve as a metaphorical depiction of a world discolored and distorted by the threat and the mandate of constant observation. Silver is a reflective metal, but it is also a conductive metal—light bounces off it, but heat passes through it. What better analogy could there be for a world in which everything can be seen but nothing can retain its own energy?

This is the spiritual if not the political message of le Carré’s work, one that extends beyond both the historical context of the Cold War and the middlebrow confines of genre fiction. The observed world is an enervated world, a turgid and self-defeating domain, a long and pointless game in which everyone is always already compromised. If every young boy who watches a James Bond film dreams of being a spy, then le Carré’s works affirm that we are all indeed spies, whether we want to be or not, and that this is not a grand adventure but a curse of the most mundane and tedious kind.